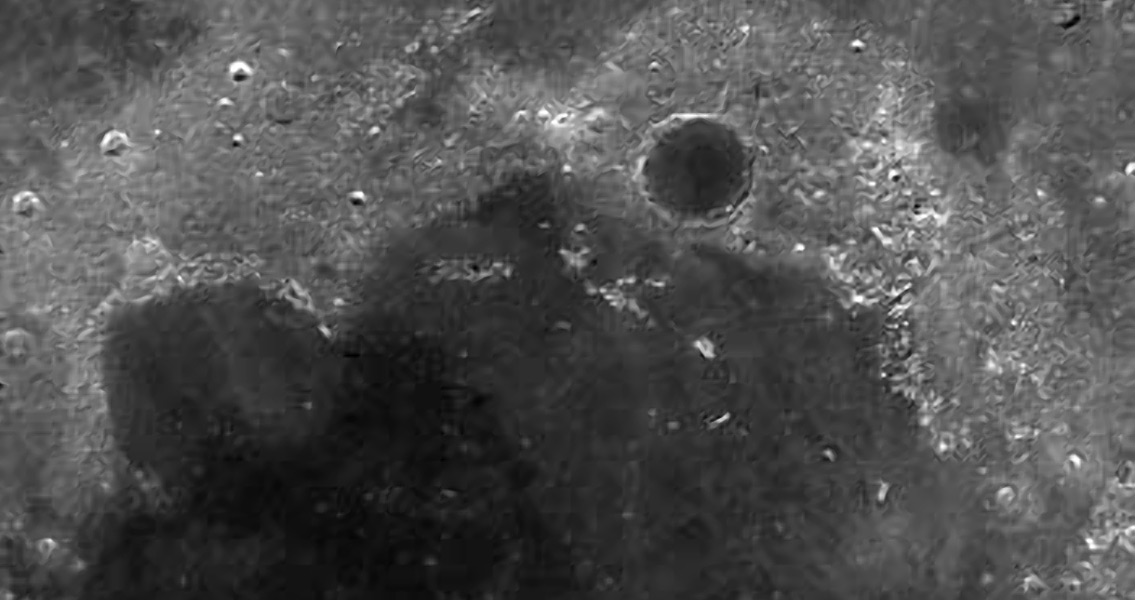

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, the discovery made through rather unpleasant means is described as momentous. It has long been thought that the Silk Road could have been a conduit for transporting diseases between Asia and Europe. Now, a 2,000 year old latrine in Western China has provided the first archaeological evidence that this was indeed the case. The findings are likely to be game changers in the history of the origin and dispersal of disease, possibly expanding our understanding of the spread of the Black Death in Asia and Europe, as well as other lethal diseases such as anthrax and leprosy. Hui-Yuan Yeh and Piers Mitchell from Cambridge University used microscopy to analyse the faeces preserved on ancient personal hygiene sticks (used to clean the anus). The sticks were unearthed from the latrine at what was a major Silk Road relay station on the eastern border of the Tamrin Basin, a region that includes the Taklamakan Desert. The researchers believe the latrine dates from 111 BCE and was in use until 109 CE. Chinese researchers Ruilin Mao and Hui Wang from the Gansu Institute for Cultural Relics and Archaeology carried out the initial excavations at the site in Gansu province. The relay station was a popular one, used by travellers as a place to stay, and government officials as somewhere to change horses and deliver letters. Mao and Wang found the hygiene sticks with cloth wrapped around one end. Four eggs from four parasitic worms were present in the faeces studied: roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), tapeworm (Taenia sp.), and Chinese liver fluke (Clonorchis sinensis). The Chinese liver fluke provided the key evidence that infectious diseases could be spread over thousands of miles. A parasitic flatworm that causes abdominal pain, diarrhoea, jaundice and liver cancer, Chinese liver fluke requires well-watered, marshy areas to complete its life cycle, nothing like the dry, arid, desert-like environment the relay station was situated in. The liver fluke is simply not endemic to this region, and must have come from elsewhere. At present, the closest endemic area to the relay station for the Chinese liver fluke is Dunhuang, around 1,500 km away. The species is most prevalent in Guandong Province, some 2,000 km from Dunhuang. The authors of the study, from Cambridge University’s Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, argue that the person infected with the liver fluke must have traveled a substantial distance while infected with the parasite. As such, the finding presents the earliest archaeological evidence of diseases being carried large distances along the Silk Road. “When I first saw the Chinese liver fluke egg down the microscope I knew that we had made a momentous discovery,” said Hui-Yuan Yeh, in a press release from Cambridge University. “Our study is the first to use archaeological evidence from a site on the Silk Road to demonstrate that travellers were taking infectious diseases with them over these huge distances.” First coming to prominence during the period of the Han Dynasty in China (202 BCE – 220 CE), the Silk Road allowed merchants, explorers, soldiers and officials to travel between East Asia and the Middle East/Eastern Mediterranean. The fact that similar strains of bubonic plague, anthrax and leprosy have been found in both China and Europe has led many researchers to suggest the Silk Road was the conduit that spread the diseases, but archaeological evidence supporting this theory had been lacking. “Until now there has been no proof that the Silk Road was responsible for the spread of infectious diseases. They could instead have spread between China and Europe via India to the south, or via Mongolia and Russia to the north,” said Piers Mitchell, one of the study authors. “Finding evidence for this species in the latrine indicates that a traveller had come here from a region of China with plenty of water, where the parasite was endemic. This proves for the first time that travellers along the Silk Road really were responsible for the spread of infectious disease along this route in the past.” Image courtesy of Hui-Yuan Yeh. Reproduced from the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.]]>