th July 1518, a townswoman named Frau Troffea began to dance in the streets of Strasbourg. For hours she swayed, gathering a small crowd of bemused onlookers. Eventually, she collapsed from exhaustion. When she came to, she recommenced her jig; this time with frenzied abandon, dancing until her feet were bruised and bloody.

Rumours flew about the town. Supernatural in their beliefs, the people soon decided that she had succumbed to a dancing curse bequeathed by St. Vitus. To calm divine rage, they carted her off to a shrine in the Vosges Mountains.

But Frau Troffea was not alone in this curse. As the days turned into weeks, between 200 and 400 people fell victim to St. Vitus’ Dance. An outbreak of frantic delirium had the city of Strasbourg in its grip. What caused it? What cured it? And what relevance does it have today?

As the dancing plague, or choreomania, was a psychological affliction, we must first understand the psychology of the townsfolk.

Like much of medieval Europe, Strasbourg was steeped in supernaturalism. Their Christianity functioned on a foundation of saint-worship, and the clergy was responsible for the immortal path of every individual.

The local reputation of the Strasbourg clergy had been declining for decades. Repeated accounts of moral indiscretions (the usual: sex, alcohol and excess) were further substantiated when, during times of famine, the Church was unwilling to provide aid to starving townsfolk. In private, ale-fuelled discussions questioned the opulence of the Church, and bitterly remarked on the contrast with Christ, for all his sublime poverty.

Famines continued during the years leading up to 1518. The chilling uncertainty of a world in which disease could suddenly sweep away family and friends left people with a constant, bubbling anguish. With death constantly looming, it was essential for one’s soul to be in the hands of a responsible clergy. For the superstitious and anxious residents of Strasbourg, the afterlife was an increasingly alarming concept.

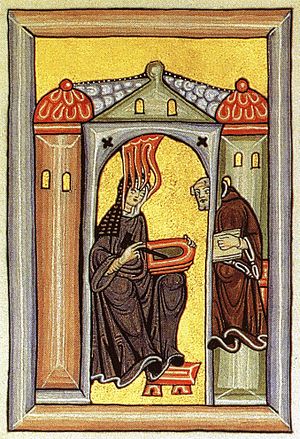

The cult of St. Vitus

Psychologically, there’s an argument to say that the victims were expecting demons to commandeer their souls. Legends of dancing plagues, culturally connected to St. Vitus, had passed down generations. Day to day, insults like “God give you St. Vitus” were thrown about, weaving the cult of St. Vitus into common parlance.

Perpetuating their worry, the people of Strasbourg believed their own baptisms to be phony, as their priests associated with prostitutes. This pessimism mixed with mysticism to make the people paranoid of the touch of a raging St. Vitus.

[caption id="attachment_8660" align="aligncenter" width="640"] Modern Strasbourg. Photo by R Roletschek.[/caption]

Finding a cure

The city’s council was tasked with finding a cure for the curse. Frau Troffea may have been taken off into the mountains, but the remaining afflicted were subject to panicked ideas of treatment.

At first, it was thought that the plague came from ‘hot blood,’ and as such, only continued dancing could sweat it out. The council erected a stage, hired musicians and dancers and made sure that the afflicted continued to dance at a fast pace.

Matters worsened. Many of those hired fell subject to the curse, as did petrified onlookers. Within a few days, the council’s theory of forcing the dance to extinguish ‘hot blood’ had been discredited.

For the dancers, medical attentions were irrelevant. They needed the mercy of St. Vitus and support from a neglectful Church. Luckily, the flattering attentions of priests were about to be bestowed upon them.

They were given sacred red shoes and started a pilgrimage to Saverne. It involved a gruelling climb to a remote monastery, which was thick with incense and candle smoke. This extravagant ritual awoke something in their deep-rooted piety. Between holy relics and religious imagery, they had reason to believe the curse would be raised. and the curse was lifted.

Why did the pilgrimage lift the curse?

Dr. John Waller, author of A Time To Dance, A Time To Die, hypothesises that ‘the large number of people who recovered through the power of religious suggestion reveals that even when self-awareness is impaired, our minds can still receive, process and respond to appropriate external stimuli.’

These were a people calling out for attention from the Church. They’d been neglected for years, but in the recent weeks, civic and religious leaders had changed their attitudes toward their flock. Just as neglect has immense psychological potential, so too does religious attention.

Cultural conventions and pathological anxiety

In the decades that followed, Martin Luther’s attractively egalitarian ideals diverted the Christian psyche away from supernaturalism. Outbreaks of choreomania disappeared; but the phenomenon provides a fundamental commentary on group psychosis.

Biologically speaking, 500 years is not a long time. When under pressure, the human brain still causes relatively expected behaviour. A person may appear to have lost control completely, but they still reflect some kind of cultural prescription.

Whether supernatural or not, cultural conventions play a key role in the expression of pathological anxiety. Set in the context of a people who feared St. Vitus, the dancing plague of Strasbourg offers us a fascinating insight into the ways pathological anxiety can play out.]]>

Modern Strasbourg. Photo by R Roletschek.[/caption]

Finding a cure

The city’s council was tasked with finding a cure for the curse. Frau Troffea may have been taken off into the mountains, but the remaining afflicted were subject to panicked ideas of treatment.

At first, it was thought that the plague came from ‘hot blood,’ and as such, only continued dancing could sweat it out. The council erected a stage, hired musicians and dancers and made sure that the afflicted continued to dance at a fast pace.

Matters worsened. Many of those hired fell subject to the curse, as did petrified onlookers. Within a few days, the council’s theory of forcing the dance to extinguish ‘hot blood’ had been discredited.

For the dancers, medical attentions were irrelevant. They needed the mercy of St. Vitus and support from a neglectful Church. Luckily, the flattering attentions of priests were about to be bestowed upon them.

They were given sacred red shoes and started a pilgrimage to Saverne. It involved a gruelling climb to a remote monastery, which was thick with incense and candle smoke. This extravagant ritual awoke something in their deep-rooted piety. Between holy relics and religious imagery, they had reason to believe the curse would be raised. and the curse was lifted.

Why did the pilgrimage lift the curse?

Dr. John Waller, author of A Time To Dance, A Time To Die, hypothesises that ‘the large number of people who recovered through the power of religious suggestion reveals that even when self-awareness is impaired, our minds can still receive, process and respond to appropriate external stimuli.’

These were a people calling out for attention from the Church. They’d been neglected for years, but in the recent weeks, civic and religious leaders had changed their attitudes toward their flock. Just as neglect has immense psychological potential, so too does religious attention.

Cultural conventions and pathological anxiety

In the decades that followed, Martin Luther’s attractively egalitarian ideals diverted the Christian psyche away from supernaturalism. Outbreaks of choreomania disappeared; but the phenomenon provides a fundamental commentary on group psychosis.

Biologically speaking, 500 years is not a long time. When under pressure, the human brain still causes relatively expected behaviour. A person may appear to have lost control completely, but they still reflect some kind of cultural prescription.

Whether supernatural or not, cultural conventions play a key role in the expression of pathological anxiety. Set in the context of a people who feared St. Vitus, the dancing plague of Strasbourg offers us a fascinating insight into the ways pathological anxiety can play out.]]>