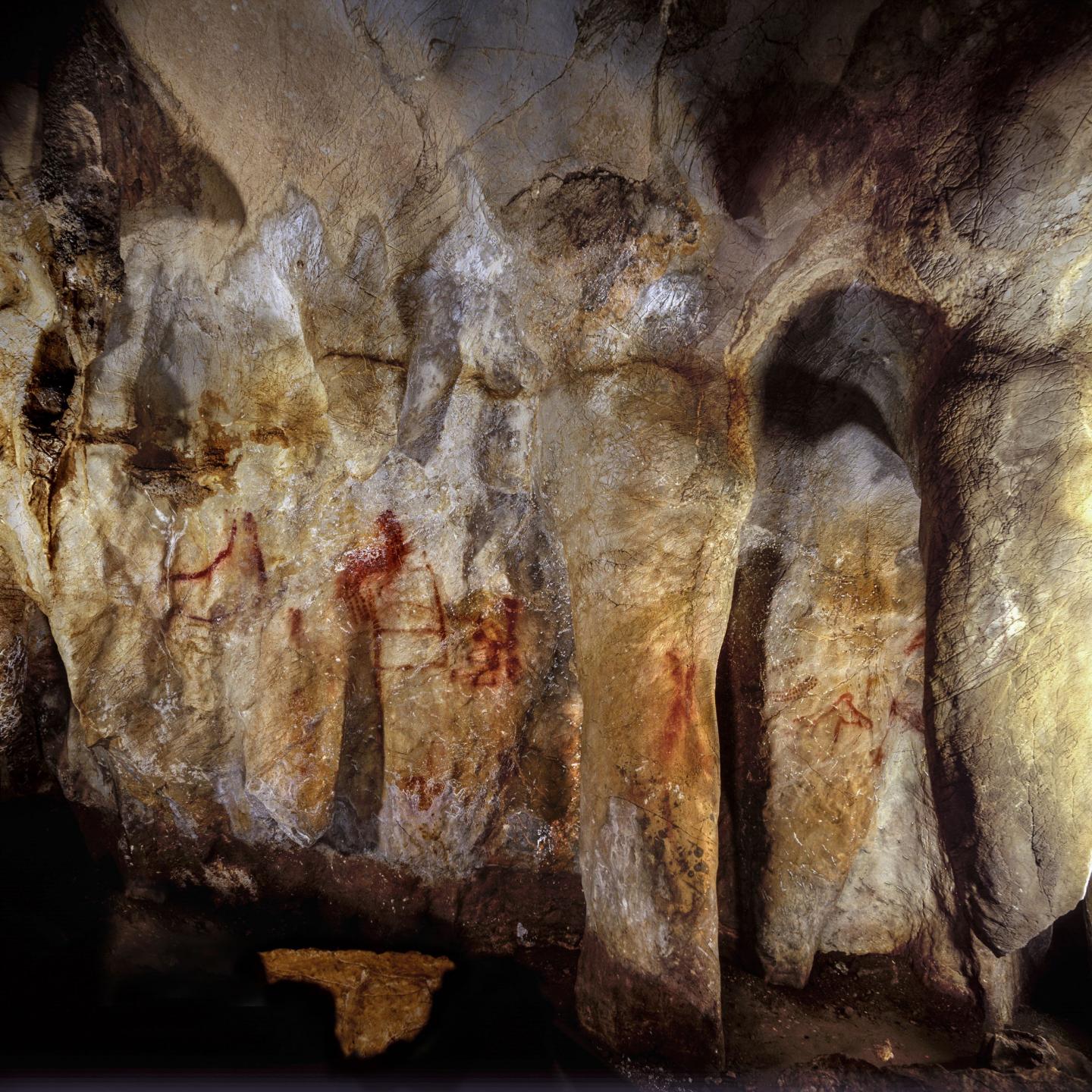

Neanderthals Created 64,000 Year-Old Cave Paintings Neanderthals, and not humans, created the world’s oldest cave paintings, new research claims. The findings add to growing evidence that our closest extinct evolutionary cousins were far from their barbaric, unsophisticated representation in popular culture. Scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and University of Southampton show that paintings in three Spanish caves are over 64,000 years old. That’s 20,000 years before the first humans arrived in Europe. The research has been published in the journal Science. It suggests that Neanderthals thought symbolically, an attribute usually only attributed to modern humans. “Artefacts whose functional value lies not so much in their practical but rather in their symbolic use are proxies for fundamental aspects of human cognition as we know it,” said Dirk Hoffmann, from the Max Planck Institute, in a press release. Cave painting has, until now, been entirely attributed to modern humans, largely due to difficulties in dating it precisely. The international team behind the new study used the uranium-thorium method to date tiny carbonate deposits that have built up on top of the cave paintings. Traces of uranium and thorium indicate when the deposits formed. This allows a minimum age for the paintings underneath to be determined. Joint lead author Dr Chris Standish, an archaeologist at the University of Southampton, said: “This is an incredibly exciting discovery which suggests Neanderthals were much more sophisticated than is popularly believed. “Our results show that the paintings we dated are, by far, the oldest known cave art in the world, and were created at least 20,000 years before modern humans arrived in Europe from Africa – therefore they must have been painted by Neanderthals.” Infant Cranial Modification Linked to Identity in Ancient Andes A new study claims that the binding and reshaping of infants’ skulls in the Andes between 1100 and 1450 was linked to identity and inequality. Prior to the expansion of the Inca Empire into the region that is now Peru, cranial modification of infants was hugely popular. Assistant professor of anthropology at Cornell University Matthew Velasco argues that these head-shaping practices were connected to political solidarity and social inequality. The anthropologist analysed hundreds of skeletal remains from multiple tombs in the Colca Valley of highland Peru. One key finding was that modification grew in popularity over the period of investigation. Prior to 1300, cranial modification was rare, while by the end of the period it had risen to 73.7% of the population. “The increased homogeny of head shapes suggests that modification practices contributed to the creation of a new collective identity and may have exacerbated emerging social differences,” Velasco said. “Head shape would be an obvious signifier of affiliation and could have encouraged unity among elites and increased cooperation in politics.” Velasco found that women with modified heads had better access to varied food options and were less likely to encounter violence in their lives. This, he suggests, points to a connection between cranial modification and inequality. A sixteenth century Spanish colonial document Velasco examined described groups moulding skulls into the shapes of volcanoes from their origin myth. “If this is true, then cranial modification reflects a deeply religious worldview and was fundamental to a person’s being and existence, and not simply a fashion statement,” Velasco said. Velasco’s findings have been published in the journal Current Anthropology. Ninth Century Rock Art Destroyed Unique paintings on a ninth century temple in Hyderabad have been whitewashed by villagers, according to the Times of India . The cave temples, located on a hillock, are one of the oldest structures in the region. However, their artworks were not on any protected lists for archaeological sites. “They were initially Jain caves that were later converted into a Lord Shiva temple after installation of shivalingam. During the recent Shivaratri celebrations, the villagers whitewashed the paintings on the pillars and cave walls,” Aravind Arya Pakide, an archaeology expert, told the Times of India. “It is complicated to restore these paintings. In the name of beautification, they are using acrylic paints and damaging the archaeologically-significant structures.” Ceiling paintings on an ornate gateway have been particularly badly affected, with only traces of the figures depicted remaining, the Times of India article reports. Featured image: La Pasiega, Section C, Cave Wall With Paintings. The ladder shape composed of red horizontal and vertical lines (centre left) dates to older than 64,000 years and was made by Neanderthals. Image credit: © P. Saura ]]>