Research Confirms Remains are Amelia Earhart’s

Forensic research has confirmed that bones found on a South Pacific Island are likely those of Amelia Earhart.

In the 1940s, physician D.W. Hoodless performed bone measurements on the remains found on the island, and concluded they belonged to a man.

Now, professor Richard Jantz from University of Tennessee has re-examined seven of the bone measurements performed by Hoodless. Using modern quantitative techniques, he concludes that Hoodless was incorrect in determining the remains to be a man’s.

Significantly, Jantz’s results show that the remains are more similar to Earhart’s than to 99% of individuals in a large reference sample.

The bones were also compared to the bone lengths of Earhart’s. To achieve this, her humerus and radius lengths were determined through studying a photo that included a scalable object.

“Until definitive evidence is presented that the remains are not those of Amelia Earhart, the most convincing argument is that they are hers,” Jantz writes in a study, published in the journal Forensic Anthropology.

Famous for being the first female aviator to fly solo across the Atlantic, Earhart and her navigator Fred Noonan mysteriously disappeared in 1937 while flying across the Pacific. Many assume her aircraft crashed into the ocean, yet some experts, such as Jantz, argue she died as a castaway on the island of Nikumaroro.

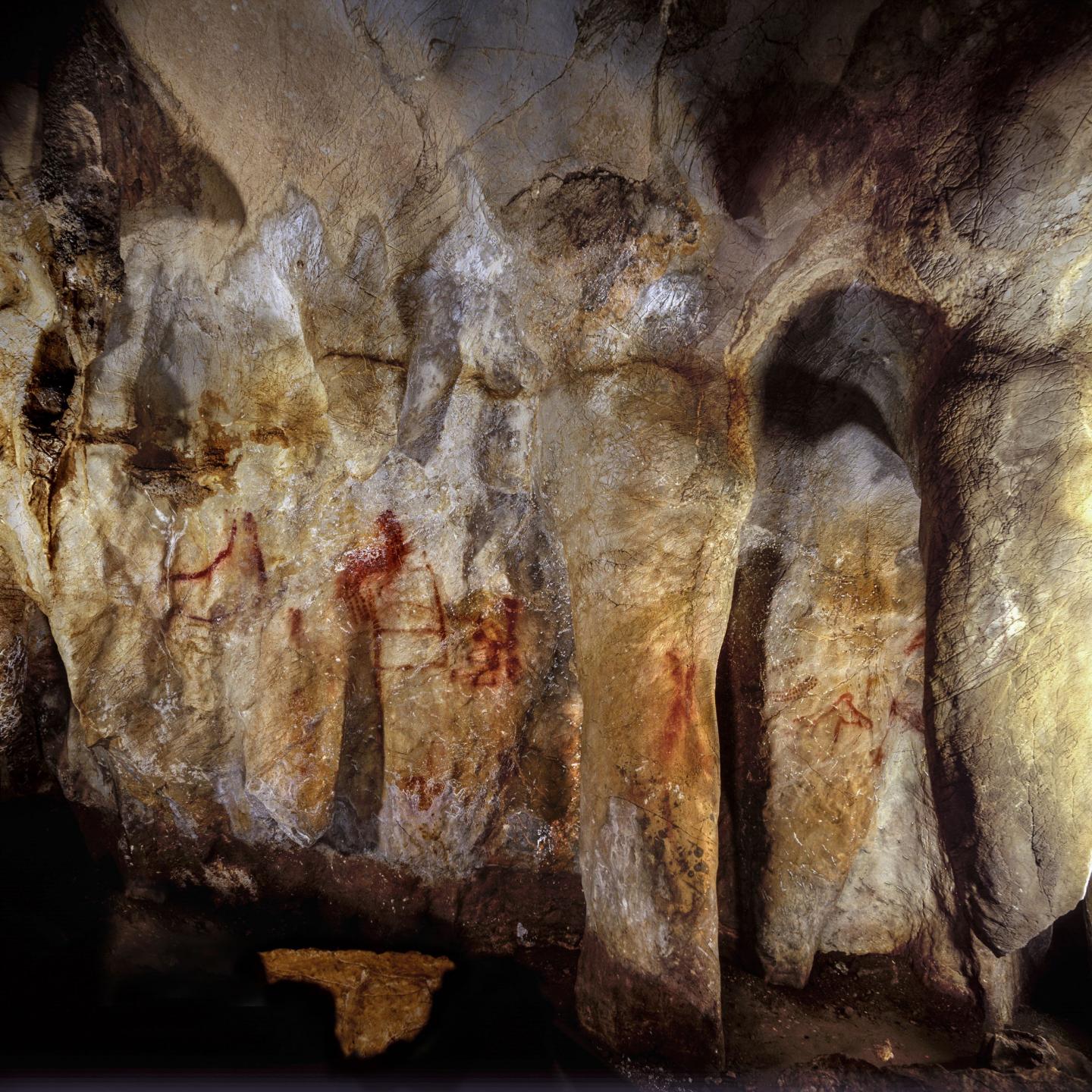

Nicotine Extracted From Ancient Teeth

Researchers have shown for the first time that nicotine residue can be extracted from the plaque of ancient tobacco users.

The pioneering research could allow archaeologists to trace the history of tobacco consumption far back into prehistory.

“The ability to identify nicotine and other plant-based drugs in ancient dental plaque could help us answer longstanding questions about the consumption of intoxicants by ancient humans,” said Shannon Tushingham, a WSU assistant professor of anthropology and co-author of the new study.

“For example, it could help us determine whether all members of society used tobacco, or only adults, or only males or females.”

Until now, the history of tobacco use in the Americas has been traced through the presence of pipes, charred tobacco seeds and the analysis of hair and fecal matter. However, these items are sparse in the archaeological record and can’t be tied to specific individuals.

These problems don’t exist with dental matter, which preserves a wide range of substances and can be easily connected to an individual.

Tushingham, along with colleagues from WSU and the University of California Davis, collaborated with members of the Ohlone tribe in the San Francisco Bay to extract plaque from the teeth of eight individuals buried between 6,000 and 300 years ago.

After the plaque had been extracted with regular, everyday dental picks, it was sent to WSU labs. There, it was analysed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry to test for samples of nicotine and other plant-based drugs such as caffeine.

Two of the samples tested positive for nicotine, showing for the first time that the drug can survive in detectable amounts in ancient plaque.

One of the most interesting findings was the presence of nicotine in the plaque of an older woman.

“While we can’t make any broad conclusions with this single case, her age, sex, and use of tobacco is intriguing,” Jelmer Eerkens, an anthropologist from UC Davis who worked on the study, said.

“She was probably past child-bearing age, and likely a grandmother. This supports recent research suggesting that younger adult women in traditional societies avoid plant toxins like nicotine to protect infants from harmful biochemicals, but that older women can consume these intoxicants as needed or desired.”

The study has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Caption: This is a 1945 picture of a Yokuts Native American woman smoking a pipe.

Credit: Clifford Relander

New Insights into Early Pacific Settlers

Researchers from the Australian National University claim to have produced ‘the most comprehensive study ever’ into the origins of people on the Pacific island of Vanuatu.

Vanuatu is considered crucial to the history of migration and population of the Pacific, acting as a gateway from Asia to the ocean’s remotest islands.

The results, published across two papers, confirm that the first people on Vanuatu were of the Lapita culture and arrived 3,000 years ago from South East Asia. This was followed by Papuan arrivals from the island of New Britain, part of what is now Papua New Guinea.

Archaeological evidence was combined with analysis of ancient and modern DNA to make the conclusions.

Dr Stuart Bedford, of the ANU School of Culture History and Language, highlighted the unique insights the study has made.

“We’ve been able to track a complete genetic timeline at regular intervals starting with the first inhabitants right through to modern times,” Dr Bedford said.

“The very first generation of people into Vanuatu are primarily Asian, then very quickly you see a series of migrations of Papuan people from the Bismarck Archipelago who had been living in the region for around 50,000 years.

“That trend continues over the next 3,000 years right up until today as the genetic ancestry was mostly replaced by that of Papuan migrants. The people of Vanuatu today, like many peoples of the Pacific, can claim a dual heritage.”

According to Professor Matthew Spriggs, a co-researcher on the study, the findings show where the Papuan migration came from.

“They came from New Britain, a Papuan island just east of New Guinea,” Professor Spriggs said.

“This makes sense. New Britain has some of the earliest known Lapita sites.

“So what we think happened is that Lapita people after arriving in New Britain moved fairly directly on to Vanuatu and encouraged some of the local populations already in place on New Britain to move there as well.”

The influence of the Lapita culture can still be felt in the languages of the region.

“The Lapita people who originally came to Vanuatu from South East Asia spoke a form of Austronesian,” Dr Bedford said.

“That language persisted and over 120 descendant languages continue to be spoken today, making Vanuatu the most linguistically diverse place on Earth per capita.

“This is a unique case, where a population’s genetic ancestry was replaced but its languages continued.”

]]>

Caption: This is a 1945 picture of a Yokuts Native American woman smoking a pipe.

Credit: Clifford Relander

New Insights into Early Pacific Settlers

Researchers from the Australian National University claim to have produced ‘the most comprehensive study ever’ into the origins of people on the Pacific island of Vanuatu.

Vanuatu is considered crucial to the history of migration and population of the Pacific, acting as a gateway from Asia to the ocean’s remotest islands.

The results, published across two papers, confirm that the first people on Vanuatu were of the Lapita culture and arrived 3,000 years ago from South East Asia. This was followed by Papuan arrivals from the island of New Britain, part of what is now Papua New Guinea.

Archaeological evidence was combined with analysis of ancient and modern DNA to make the conclusions.

Dr Stuart Bedford, of the ANU School of Culture History and Language, highlighted the unique insights the study has made.

“We’ve been able to track a complete genetic timeline at regular intervals starting with the first inhabitants right through to modern times,” Dr Bedford said.

“The very first generation of people into Vanuatu are primarily Asian, then very quickly you see a series of migrations of Papuan people from the Bismarck Archipelago who had been living in the region for around 50,000 years.

“That trend continues over the next 3,000 years right up until today as the genetic ancestry was mostly replaced by that of Papuan migrants. The people of Vanuatu today, like many peoples of the Pacific, can claim a dual heritage.”

According to Professor Matthew Spriggs, a co-researcher on the study, the findings show where the Papuan migration came from.

“They came from New Britain, a Papuan island just east of New Guinea,” Professor Spriggs said.

“This makes sense. New Britain has some of the earliest known Lapita sites.

“So what we think happened is that Lapita people after arriving in New Britain moved fairly directly on to Vanuatu and encouraged some of the local populations already in place on New Britain to move there as well.”

The influence of the Lapita culture can still be felt in the languages of the region.

“The Lapita people who originally came to Vanuatu from South East Asia spoke a form of Austronesian,” Dr Bedford said.

“That language persisted and over 120 descendant languages continue to be spoken today, making Vanuatu the most linguistically diverse place on Earth per capita.

“This is a unique case, where a population’s genetic ancestry was replaced but its languages continued.”

]]>