Memorial “to the gay and lesbian victims of National Socialism” in Cologne: The inscription on the left side of the monument (to the viewer’s right from the angle depicted) reads “Totgeschlagen – Totgeschwiegen” (“Struck Dead – Hushed Up”). Credit: Jörg Lenk via Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Memorial “to the gay and lesbian victims of National Socialism” in Cologne: The inscription on the left side of the monument (to the viewer’s right from the angle depicted) reads “Totgeschlagen – Totgeschwiegen” (“Struck Dead – Hushed Up”). Credit: Jörg Lenk via Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Female oppression as a cause for the tolerance of lesbians?

Some have argued that lesbians weren’t as harshly persecuted as gay men, simply because female sexuality wasn’t taken seriously. Others have said that the regime’s policy of pronatalism, which encouraged reproduction and the nuclear family, didn’t face as much of a threat from lesbians as it did gay men. Further still, the Nazis believed women were inferior to men and thus dependent on them. Under this theory, a lesbian would still rely on the men in her community, and is hardly a threat to male dominance. The Nazis also dismissed lesbianism as they believed lesbians could still occupy a German woman’s primary role: to mother as many German babies as possible. Sexuality, they believed, did not interfere with a woman serving the Nazi state as a wife and mother. There is another prominent narrative, which has gained attention over the past year. Samuel Clowes Huneke from Stanford University posits that Nazi officials didn’t see lesbians as a strong political threat, due to the fact that women were barred from politics and public life. “In light of both the fearsome persecution of homosexual men and scholarship that places it in the context of National Socialist pronatalism, the regime’s seeming lack of interest in female homosexuality is startling, for in other respects the government placed considerable burdens on women,” says Huneke.Four couples betrayed

Specialising in homosexuality in the Third Reich, Huneke has examined 4 cases of investigation by the Kriminalpolizei, or the German criminal police. Discovered at the Landesarchiv Berlin in 2015, the files shed light on the investigation of 8 women. They show us signed statements from witnesses and the women themselves. In all 4 of the cases, the women were accused by a person they knew and trusted: whether that was a neighbour, co-worker or even a parent. “That these eight women were denounced to the Berlin criminal police in the early 1940s is striking on its own, given the archival silence when it comes to female homosexuality,” Huneke says. Astonishingly, there is no evidence that any of the 8 women were punished as a result. All 4 cases tell us that the women could not be prosecuted for same-sex relations under the criminal code, in the way that gay men would have been. Huneke was fascinated: “To scholars accustomed to seeing in the Nazi state a jungle of overlapping jurisdictions, personal initiative and law based solely on the Führer’s wish, this is a curious portrait of the Nazi justice system, one marked by an unexpected concern for the strict interpretation of statute.” One case stands out as particularly peculiar. Margot Liu née Holzmann was a Jewish lesbian living in Berlin. In 1941, she married a male Chinese waiter and received Chinese citizenship, which protected her from being deported to a concentration camp. However, when her husband discovered she was in a lesbian relationship, he filed for divorce and reported her to the police. Curiously, the police did not intervene. Moreover, they insisted, in multiple documents, that she was protected because of her Chinese citizenship – despite being a German Jewish lesbian. At this point, it is worth noting that in all 4 of these cases, including Margot Holzmann, we are looking at the judgment of one single officer. That particular officer may have just been less inclined to pursue homophobic policy than other officers. However, the rules were very closely followed, which has led some historians to consider this to be an indication of relative tolerance for lesbians.“Open – but not enviable – lives”

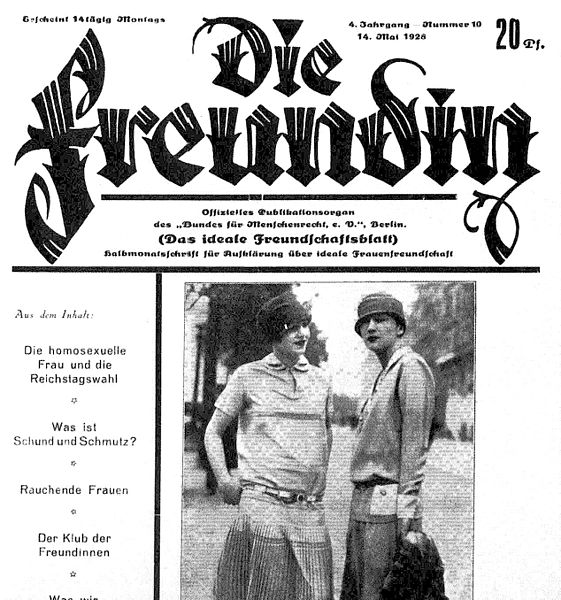

The files show that the 8 women had led relatively open – though certainly not enviable – lives as lesbians before being denounced to the authorities. Ordinary German citizens would have been aware of their female friends, co-workers and acquaintances in same-sex relationships, but were less likely to report them to the police. A patronising understanding of female sexuality comes into play: “Gender is perhaps why lesbians weren’t persecuted in the same ways… [but] these files throw into sharper relief the duplicity of tolerance that has characterised societies’ views of female sexuality for centuries,” says Huneke. By no means was life as a lesbian in Nazi Germany easy, though. In 1928, for example, the police banned popular lesbian journals such as Die Freundin (Girlfriend) based on the Protection of Youth from Obscene Publications Act. [caption id="attachment_8709" align="aligncenter" width="561"] Credit: Bund für Menschenrecht/Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Many conservatives are documented as demanding the enactment of criminal statutes against lesbian sexual acts.

Pamphlets with messages against homosexuals, feminists, Republicans and Jews were everywhere, usually bringing with them the ideas of a conspiracy from marginalised peoples to destroy Germany. These pamphlets denounced the movement for women’s rights, saying that feminism was nothing more than a seduction into lesbianism.

Culturally, it seems there was a war against lesbians; and yet there appears to be at least some level of tolerance when it came to prosecution.

Credit: Bund für Menschenrecht/Wikimedia Commons[/caption]

Many conservatives are documented as demanding the enactment of criminal statutes against lesbian sexual acts.

Pamphlets with messages against homosexuals, feminists, Republicans and Jews were everywhere, usually bringing with them the ideas of a conspiracy from marginalised peoples to destroy Germany. These pamphlets denounced the movement for women’s rights, saying that feminism was nothing more than a seduction into lesbianism.

Culturally, it seems there was a war against lesbians; and yet there appears to be at least some level of tolerance when it came to prosecution.