Science. According to Hershkovitz, the findings provide new context for a range of other recent discoveries.

“Our research makes sense of many recent anthropological and genetic finds,” Prof. Hershkovitz said. “About a year ago, scientists reported finding the remains of modern humans in China dating to about 80,000-100,000 years ago. This suggested that their migration occurred earlier than previously thought, but until our discovery at Misliya, we could not explain it.

“Numerous different pieces of the puzzle — the occurrence of the earliest modern human in Misliya, evidence of genetic mixture between Neanderthals and humans, modern humans in China — now fall into place,” he continued.

Horse Evolution Mystery Solved?

The genetic ancestors of the modern horse were animals with five toes. Generally, it is believed that horses evolved to have fewer digits, but new research is challenging that theory and arguing that remnants of the five toes are still present in modern hooves.

Humans and horses actually evolved from the same common ancestor, a creature with five digits. As a consequence of living on open grassland, horses adapted to move across these plains. Scientist’s widely believe that this adaption saw horses evolve to have fewer digits. The first horse only had four digits, its later descendant had three, while modern horses have just a central digit, known as the metacarpal.

In research published in a recent issue of Royal Society Open Science, a team of scientists are proposing that rather than horses simply losing four digits, all five merged to form the compacted forelimbs with hooves seen today.

Currently, scientists accept that splints, small bones found along the outer sides of the metacarpal in modern horses, are partially formed remnants of second and fourth digits. Tapering mid-way down the metacarpal, these fragments were inherited from an earlier ancestor, but ceased to develop into fully formed digits in modern horses. The authors of the new paper claim that this theory is incomplete, failing to account for the animals’ first and fifth digits.

“With a distinct surface from the metacarpal, we know the splints on today’s horses to be the remnants of the second and fourth digits,” said Nikos Solounias, a paleontologist from New York Institute of Technology (NYITCOM) and an author on the study. “However, these partially formed digits also appear to contain their own elevated surfaces which hold additional evolutionary clues. We find these ridges, located on the posterior of each splint, to be the partially formed remains of the first and fifth digits, which were once connected to the cartilages of the hoof.”

Key to the research are the famous Laetoil footrprints in Tanzania, which show that the famous, eight-million-year-old horse known as Hipparion primigenium walked alongside early humans and had three digits. According to a NYITCOM statement, Solounias analysed the footprints and came to the conclusion that Hipparion actually had five compacted toes, the forelimb divided into five sections – suggesting the small toes had binded together.

“Interestingly, we not only find hints of the missing digits on the modern horse, but also its ancestors, such as Hipparion and Mesohippus, two species believed to have three toes,” said Solounias.

Neurovascular evidence has provided further support to the NYITCOM researchers’ theory, with dissections of modern equine foetus forelimbs revealing a greater number of arteries and nerves than would be expected in a single digit.

“If today’s horse does indeed have one digit per forelimb, we would expect each forelimb to have a total of two veins, two arteries, and two nerve bundles,” said Melinda Danowitz, a recent NYITCOM graduate who worked with Solounias on the study. “However, our dissections found between five and seven neurovascular bundles per forelimb, suggesting that additional toes begin to develop, but do not become fully differentiated.”

King Ramses Statue Moved to New Home

A colossal, 83 tonne, 3,200 year old statue of the Ancient Egyptian King Ramses II has been moved to a new home, according to Reuters. The complex operation, which saw the statue moved 400m to Cairo’s new Grand Egyptian Museum, required army engineers and specialist contractors.

Reuters reports that the statue was put inside a cage, mounted on a truck and suspended from a steel beam to help reduce the impact of any jolts during the journey. Road surfaces on the route were treated with special materials to ensure they could adequately take the massive weight of the statue.

The entire operation cost 13.6 million Egyptian pounds ($770,000).

The statue was first discovered at the Mit Rahina archaeological site in 1820. Brought to Ramses Square in Cairo in 1955, it was moved again in 2006 due to pollution and congestion, according to Reuters. It was placed in a storage area away from public view, until now.

It will be the first site visitors to the Grand Egyptian Museum will see. The museum is set to partially open this year, before its full launch in 2022.

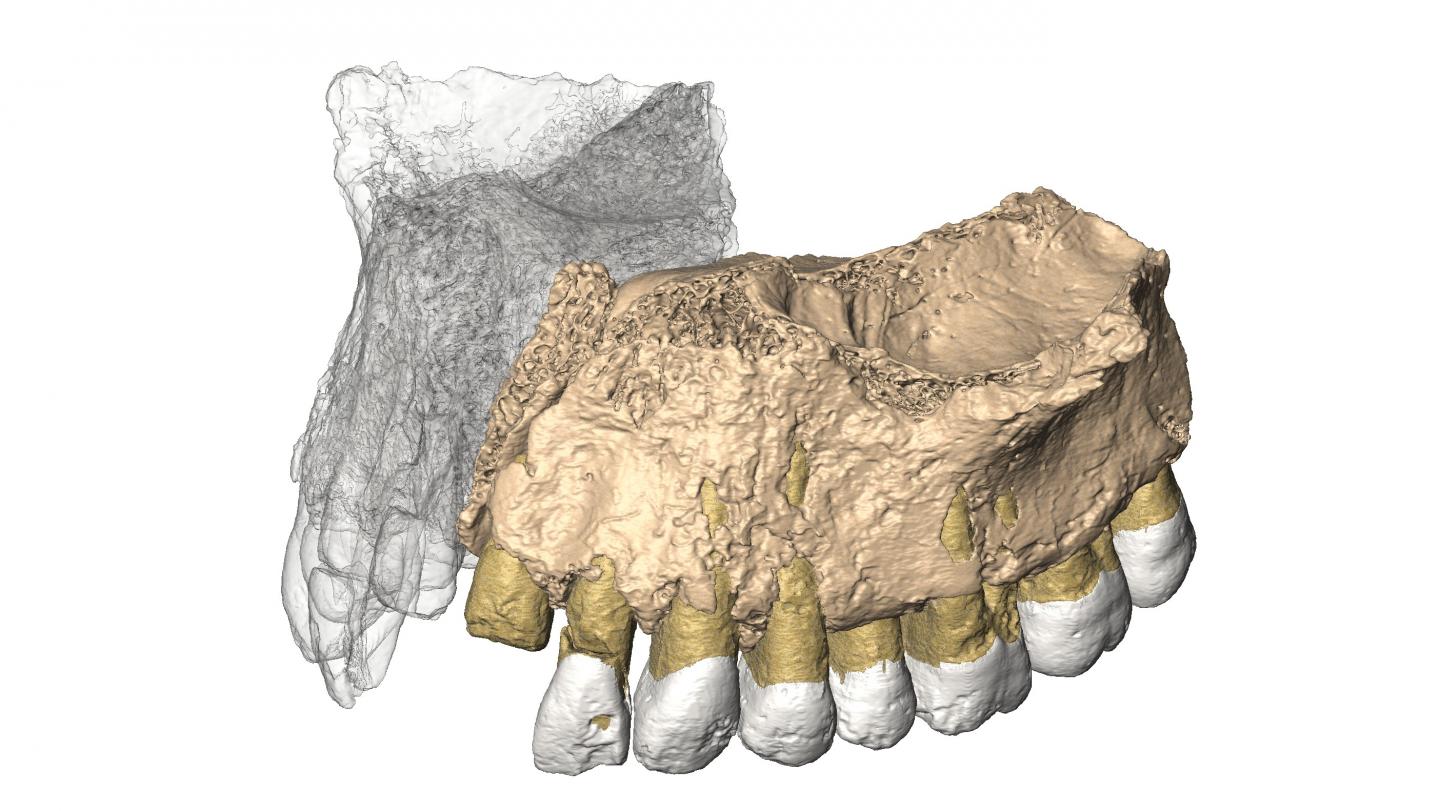

Featured image: Reconstruced maxilla from microCT images of the jawbone discovered in Israel. Image credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna, Austria]]>

Horse Evolution Mystery Solved?

The genetic ancestors of the modern horse were animals with five toes. Generally, it is believed that horses evolved to have fewer digits, but new research is challenging that theory and arguing that remnants of the five toes are still present in modern hooves.

Humans and horses actually evolved from the same common ancestor, a creature with five digits. As a consequence of living on open grassland, horses adapted to move across these plains. Scientist’s widely believe that this adaption saw horses evolve to have fewer digits. The first horse only had four digits, its later descendant had three, while modern horses have just a central digit, known as the metacarpal.

In research published in a recent issue of Royal Society Open Science, a team of scientists are proposing that rather than horses simply losing four digits, all five merged to form the compacted forelimbs with hooves seen today.

Currently, scientists accept that splints, small bones found along the outer sides of the metacarpal in modern horses, are partially formed remnants of second and fourth digits. Tapering mid-way down the metacarpal, these fragments were inherited from an earlier ancestor, but ceased to develop into fully formed digits in modern horses. The authors of the new paper claim that this theory is incomplete, failing to account for the animals’ first and fifth digits.

“With a distinct surface from the metacarpal, we know the splints on today’s horses to be the remnants of the second and fourth digits,” said Nikos Solounias, a paleontologist from New York Institute of Technology (NYITCOM) and an author on the study. “However, these partially formed digits also appear to contain their own elevated surfaces which hold additional evolutionary clues. We find these ridges, located on the posterior of each splint, to be the partially formed remains of the first and fifth digits, which were once connected to the cartilages of the hoof.”

Key to the research are the famous Laetoil footrprints in Tanzania, which show that the famous, eight-million-year-old horse known as Hipparion primigenium walked alongside early humans and had three digits. According to a NYITCOM statement, Solounias analysed the footprints and came to the conclusion that Hipparion actually had five compacted toes, the forelimb divided into five sections – suggesting the small toes had binded together.

“Interestingly, we not only find hints of the missing digits on the modern horse, but also its ancestors, such as Hipparion and Mesohippus, two species believed to have three toes,” said Solounias.

Neurovascular evidence has provided further support to the NYITCOM researchers’ theory, with dissections of modern equine foetus forelimbs revealing a greater number of arteries and nerves than would be expected in a single digit.

“If today’s horse does indeed have one digit per forelimb, we would expect each forelimb to have a total of two veins, two arteries, and two nerve bundles,” said Melinda Danowitz, a recent NYITCOM graduate who worked with Solounias on the study. “However, our dissections found between five and seven neurovascular bundles per forelimb, suggesting that additional toes begin to develop, but do not become fully differentiated.”

King Ramses Statue Moved to New Home

A colossal, 83 tonne, 3,200 year old statue of the Ancient Egyptian King Ramses II has been moved to a new home, according to Reuters. The complex operation, which saw the statue moved 400m to Cairo’s new Grand Egyptian Museum, required army engineers and specialist contractors.

Reuters reports that the statue was put inside a cage, mounted on a truck and suspended from a steel beam to help reduce the impact of any jolts during the journey. Road surfaces on the route were treated with special materials to ensure they could adequately take the massive weight of the statue.

The entire operation cost 13.6 million Egyptian pounds ($770,000).

The statue was first discovered at the Mit Rahina archaeological site in 1820. Brought to Ramses Square in Cairo in 1955, it was moved again in 2006 due to pollution and congestion, according to Reuters. It was placed in a storage area away from public view, until now.

It will be the first site visitors to the Grand Egyptian Museum will see. The museum is set to partially open this year, before its full launch in 2022.

Featured image: Reconstruced maxilla from microCT images of the jawbone discovered in Israel. Image credit: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna, Austria]]>