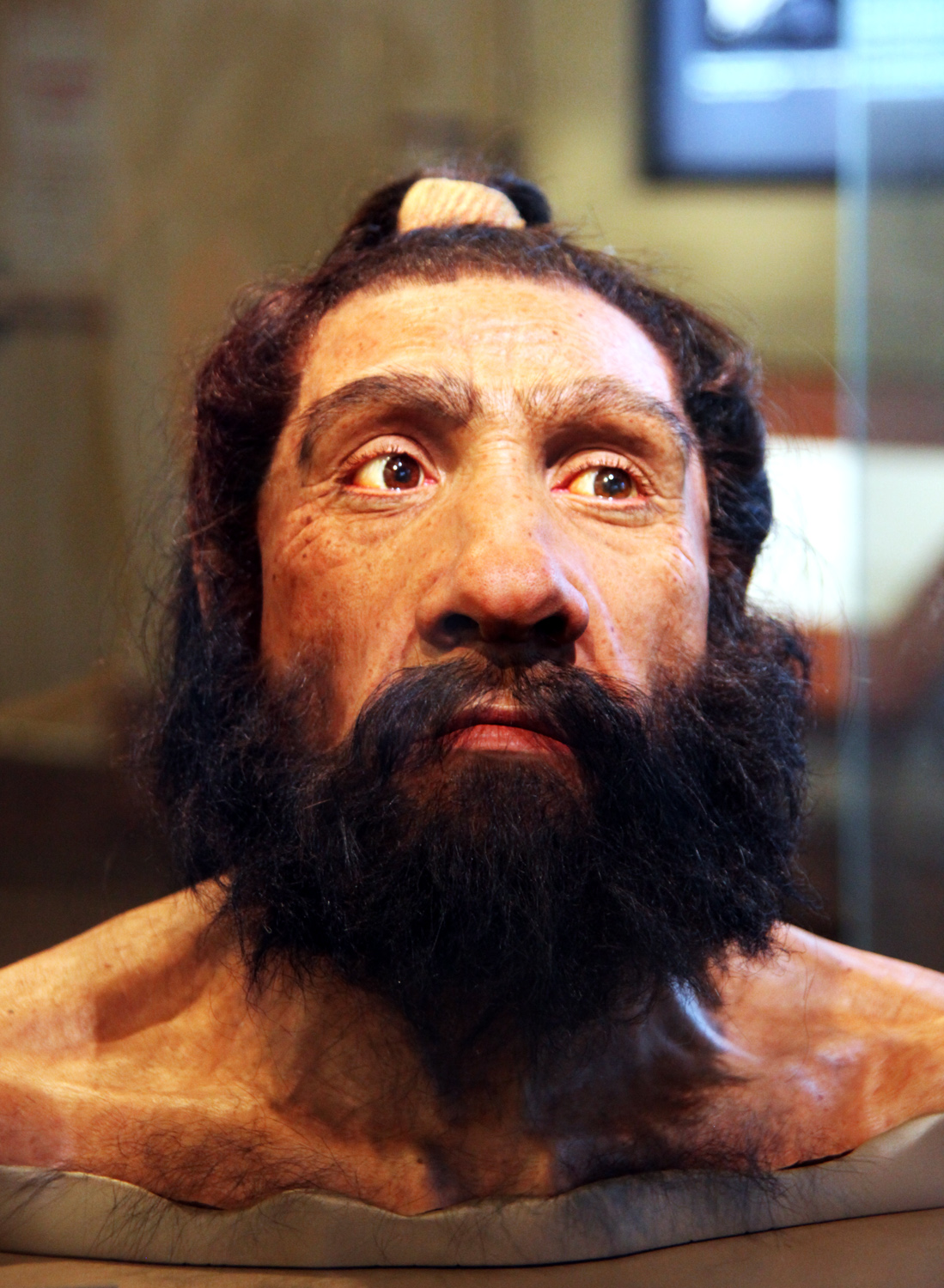

here. Controversy Surrounding King Tut’s Tomb One of the most bizarre stories of the year took place over a few months of the spring, and concerned the constantly fascinating tomb of Tutankhamun. In March, Egypt’s Antiquities Minister, Mamdouh Eldamaty, announced at a press conference that cutting edge radar scans had revealed the presence of hidden chambers in King Tutankhamun’s burial chamber. It was a revelation which sparked intrigue across the globe, as anyone with even the slightest interest in Egyptology began to speculate about what could still be hidden in the tomb of Ancient Egypt’s most famous Pharaoh. A few weeks later, doubts started to appear about the Egyptian Antiquities Ministry’s claims. Radar experts unconnected to the project started to question the findings, while others called for more evidence to be released to back up the claims and allow peer review. In May, the results of another series of scans were released, commissioned by National Geographic to verify the possibility of the existence of a hidden chamber. Announced at the Second Annual Tutankhamun Grand Egyptian Museum Conference in Cairo, the results of the second investigation suggested there was in fact no hidden chamber, directly contradicting the earlier study. The Egyptian Antiquities Authority is now carrying out additional scans in the hope of finding out once and for all if there are any more secrets to King Tut’s tomb. Just How Smart Were the Neanderthals? It’s a question that has been asked many times: just how similar are we to our closest extinct evolutionary cousins, the Neanderthals? For a long time the Neanderthals were considered to be primitive and unintelligent when compared to modern humans. Findings from 2016 however, brought that idea into question like never before. A study published in September added new fire to the long running debate over whether the Neanderthals were capable of creating jewellery. Almost since the moment they were discovered in central France half a century ago, a collection of prehistoric tiny, centimeter-long necklaces created from ivory, shells and animal teeth have been a source of contention among scientists who debate if the Neanderthals could have made the items. Using new research methods relying upon ancient proteins to date and identify bone fragments found at the site, researchers concluded that Neanderthals had lived there, supporting the idea they created the jewellery. Another study published in September carried out an in depth comparison between Neanderthal and modern human ears. The results of the pioneering research challenged the idea that Neanderthals would have only spoken in primitive grunts and groans, suggesting the possibility that Neanderthals had been capable of speech like modern humans. In December, a study from the University of Southampton revealed that Neanderthals had kept returning to the same coastal site on Jersey for a period of over 140,000 years. Through analysing stone tools, the study authors concluded that Neanderthals had kept making regular journeys back to the site for generations. The study raises interesting questions, firstly about what motivated the Neanderthals to keep returning to the site, but also about the extent to which they understood the geography around them – perhaps even some early form of mapping – to keep finding their way back there. What We Know, and What We Don’t About the History of Disease 2016 witnessed a series of shocking revelations and radical theories about the history of disease. In April, a startling study suggested that humans could have played a part in the extinction of Neanderthals by passing on a host of diseases, such as tapeworm, tuberculosis, stomach ulcers and types of herpes. The authors of the study argue that as humans left Africa, they exposed the Neanderthals to new diseases which their immune systems had not built any resistance to. Weakening the hunter-gatherer species, it would have made it harder for them to collect food, in turn causing communities to collapse. A study published in December made the shocking claim that smallpox is nowhere ear as ancient as often thought. Previously, it was believed that smallpox could be traced at least as far back as Ancient Egypt. However, a team of geneticists reconstructed the smallpox genome, based on DNA taken from the remains of victims in a crypt in Lithuania. They found that all strains of the disease had an ancestor from no further back than 1580. If true, the findings would cause a dramatic rewriting of history. Smallpox has been used by historians to explain millions of deaths and tragedies through the centuries, yet if it’s not as ancient as typically thought, such ideas will have to be rethought. Most significantly, the date of 1580 precludes the idea that the European colonisation of the Americas in the fifteenth century saw the devastating introduction of smallpox to the continent; resulting in millions of deaths for the indigenous populations. It was only in 2013 that scientists unequivocally proved that the bacteria Y.pestis played a role in both plague pandemics of the Middle Ages – the Plague of Justinian between the sixth and eighth centuries, and the second pandemic between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries that peaked with the Black Death. A study published in January 2016 revealed that a single genotype of Y.pestis had persisted in Europe from the fourteenth to the seventeenth centuries. The findings suggest that the plague survived in Europe for three hundred years in as yet unidentified reservoir. In September, a new study reconstructed the bacterial genome responsible for the Plague of Justinian. The study found that the strain of Y.pestis responsible was far more diverse than previously thought, and also infected people far beyond the region historically documented. With plague reemerging in certain parts of the world, such studies have relevance beyond history. The greater our understanding of historical plague outbreaks, the better chance we have of combating it in the present. ]]>