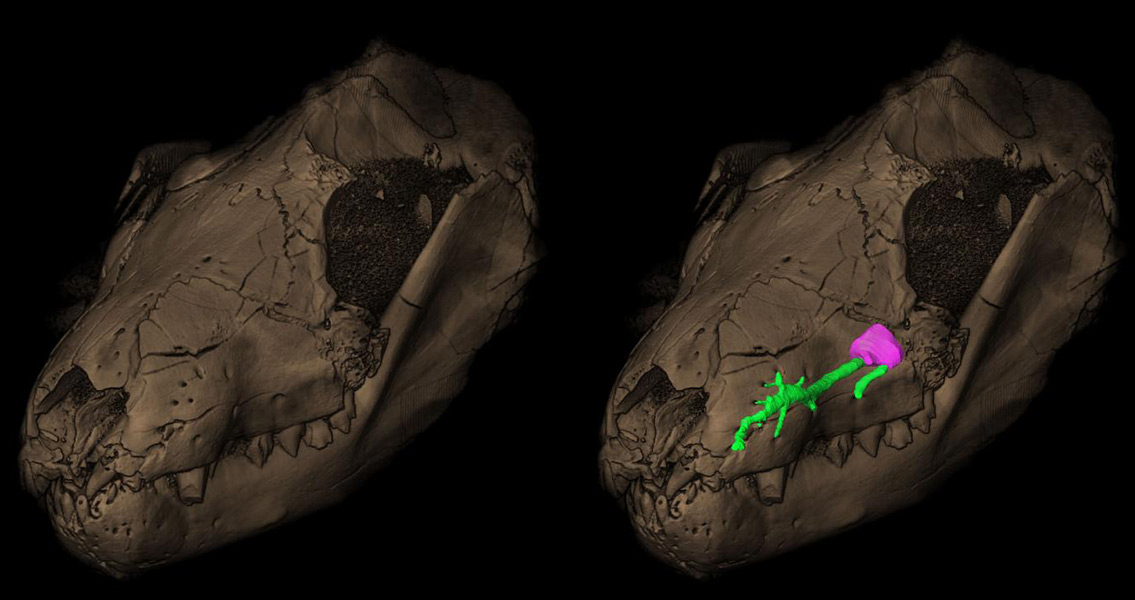

Scientific Reports, the new study suggests that something seemingly as trivial as hair, more specifically whiskers, allowed mammal like reptiles to outlive their ferocious competitors in the jungle. Dr Julien Benoit and his colleagues from the University of the Witwatersrand, Professors Paul Manger and Bruce Rubidge, studied the fossils of mammal like reptiles, known as therapsids, unearthed in the Karoo of South Africa. They found evidence that leads them to believe the therapsids may have evolved whiskers as a means to operate nocturnally during the Mesozoic Age, well before the ascendancy of the dinosaurs. “Whiskers are an amazing sensory tool to have when you are nocturnal and the evolution of whiskers possibly assisted in the survival of the therapsids – and more specifically the probainognathians – which eventually evolved into mammals as we know them today,” explained Dr. Benoit, in a press release from the University of Witwatersrand. An order of Triassic and Permian period reptiles, therapsids are widely considered the predecessors to modern mammals. It has long baffled scientists how this group of creatures were able to survive not only the competition from the dinosaurs, but also the mass extinction events that wiped out most dinosaur species. A rich fossil record exists of the therapsids, providing insight into their key role in the development of modern mammals. However, until now there was no evidence of hair among therapsids, meaning it was a development believed limited to mammals. Benoit’s team used a unique approach to solve the issue. Instead of looking for fossilised evidence of hair, they deployed scanning technology to search for the neural structures which could have allowed hair to develop in therapsids. Through computerised X-ray micro-tomography (CT scan) and digital three-dimensional modelling, Benoit discovered that therapsids had a shorter maxillary canal, a bony tube in the snout of the animal that houses the trigeminal nerve, than reptiles. The trigeminal nerve is responsible for motor functions in the face. Shortening of the maxillary canal allows for the movement of the trigeminal nerve, letting it extend into the soft tissue of the lips and nose where it innervates a creature’s whiskers. “This leaves the trigeminal nerve free to follow the movements of a flexible snout.” explained Benoit. “In reptiles this canal is long and the nerve is enclosed in the maxilla all along its length, which prevents any movement of the nose and lips,” The team’s research suggests that a mobile snout evolved between 240-246 millions years ago in the Prozostrodontia, a group of dog like therapsids which were direct ancestors of modern mammals. Research carried out on mutant mice suggests that two mammalian features, the cerebellum and the trigeminal nerve, were controlled by the same gene: MSX2. This is the gene that regulates the development of mammary glands and body hairs. As Benoit explained, “This is the gene that makes us mammals”. It seems, based on the team’s CT studies of probainognathians, the group to which Prozostrodontians belong, that MSX2 underwent a significant change in its expression 240-246 million years ago. This could have triggered the evolution of a host of mammalian traits, including hair and whiskers, an enlarged cerebellum, complete ossification of the skull roof, and more importantly, the mammary glands. Developing whiskers would have allowed therapsids to operate in the jungle at night, providing them a key advantage over dinosaurs. The animals may have been afforded the opportunity to hunt without coming into contact with their dangerous rivals. “Our research has shown that these features of mammals were already present in advanced therapsids, prior to the appearance of mammals,” says Benoit. “It also has implications for understanding how mammals survived the domination of dinosaurs during the Mesozoic period and the subsequent evolutionary success of mammals.” For more information: ww.nature.com Image courtesy of Wits University ]]>