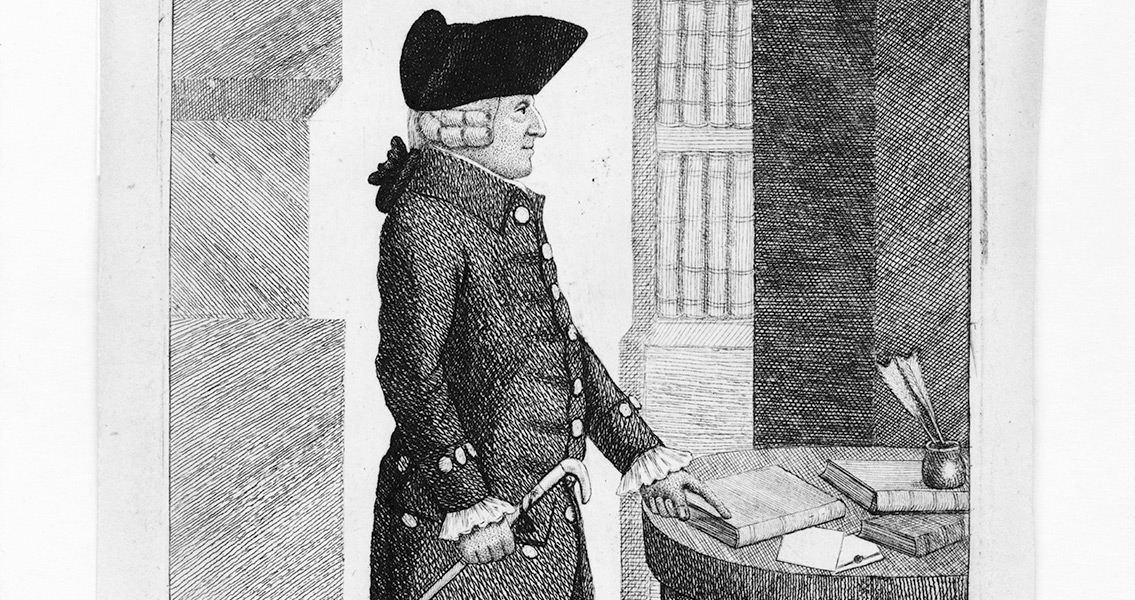

The Wealth of Nations is possibly the defining book of political economy, providing the ideological foundations for economic liberalism and laissez-faire approaches to economics. Written over a ten year period, the book was pioneering in its realisation of the political dimension to modern economics. Works on economics have of course been written throughout human history, but prior to The Wealth of Nations they tended to subjugate economics to the role of facilitator for other goals such as imperial expansion or the consolidation of governmental power. Published in 1776, Smith’s work made economics its focus, striving to explain how an economy could be run most efficiently, and how it was central to any society. The first two books of Smith’s seminal work focus on the division of labour and how it is connected to the prosperity of a society. It ultimately argues that the wealth of a nation depends on the proportion of those who are employed to those who are not, as well as the skill of the workers and the means of distributing the products of their labour. Put simply, a strong, intelligent work force increases the efficiency of production (thus encouraging the reinvestment of surpluses into educating the population). The more people who are employed, the greater the productivity of the economy, but also the more consumers there are for the products of the economy. Moving onto the third book, Smith discusses the development of societies, focusing on his native Great Britain in particular. The book charts the progression from early hunter-gatherers to the rise of agriculture and culmination in the age of international commerce. In particular, it criticises the period of feudalism across Europe following the collapse of the Roman Empire, arguing that indentured labour was an inefficient system, obstructing the progress of society. Book VI criticises the mercantile system of commerce for fixating too heavily on precious metals. Smith argues that on a national scale, true value is found in the goods and services that a nation produces and circulates. Forming the idea of Gross Domestic Product, Smith created a measure by which all modern economies are judged. Finally, Smith uses the last book to discuss ‘the revenue of the sovereign’, essentially the sources of a government’s income, but also governments’ role within the economy. It explains fair taxation, and the roles the government should play in fostering public works which facilitate education, commerce and defence. Again, the role of government is mostly located in ensuring conditions are ideal for the economy to thrive. “The subjects of every state ought to contribute towards the support of the government, as nearly as possible, in proportion to their respective abilities.” Often used as a defense of laissez-faire capitalism, it is important to point out that although a firm believer in the centrality of economy to society, in ‘The Wealth of Nations‘ Smith did not advocate ruthless consolidation of wealth by a few individuals. He argued against monopolies and lobbying groups, on the basis that they interfered with the free, natural movement of the economy. “Wherever there is great property there is great inequality. For one very rich man there must be at least five hundred poor, and the affluence of the few supposes the indigence of the many.” He explains in The Wealth of Nations, “The affluence of the rich excites the indignation of the poor, who are often both driven by want, and prompted by envy, to invade his possessions.” Critics of Smith’s work argue that he focuses too heavily on the strength of the economy and fails to take into account the moral goals it should serve in relation to the population. It is a similar criticism to that often thrown at the governments who most rigidly stick to the ideas of free market economics. However, just because Smith’s work laid the ideological basis for laissez-faire economics doesn’t mean it should also be associated with the worst excesses that have been carried out in its name.

Related Books

The Wealth of Nations

Vol. 2 of 2Vol. 2 of 2

by Adam Smith

One Comment

david

First time I’ve ever seen Smith reviewed without mention of the ‘invisible hand’, but it’s an effective way of focusing on the other elements of Wealth of Nations. If you haven’t seen his Theory of Moral Sentiments, it’s worth a look for the (supposedly) missing element of morality in Wealth of Nations. Anyway, nice, thoughtful review.