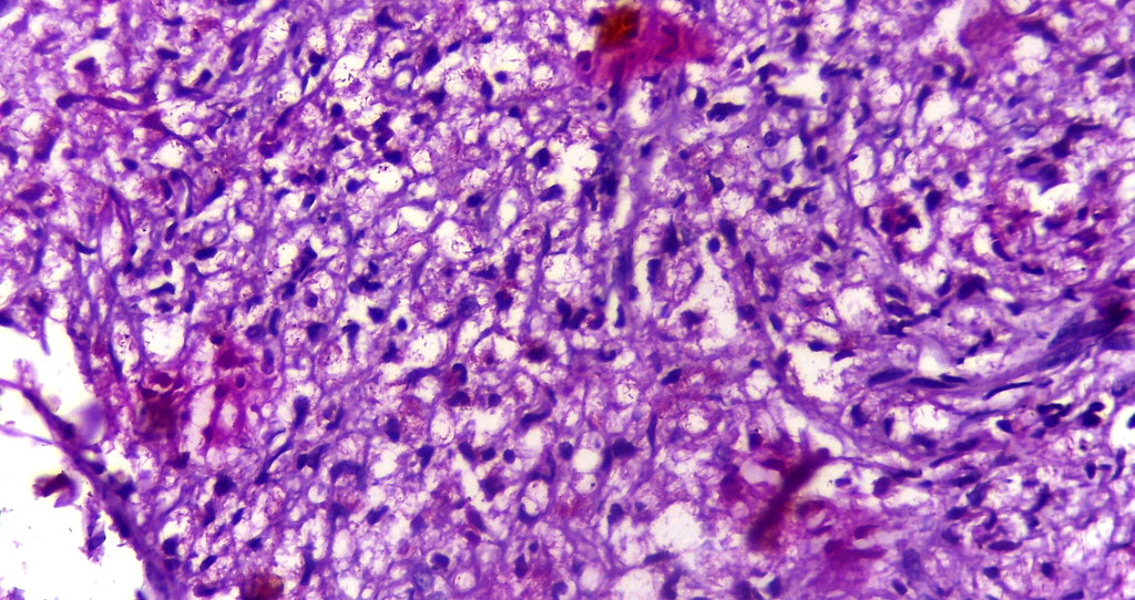

PLOS ONE. The man’s skeleton shows the signs of having been afflicted by leprosy: the toe bones have narrowed and there is damage to the joints. By conducting modern DNA testing the team confirmed that the man, probably aged in his twenties, suffered from leprosy and may well have come to Britain from southern Scandinavia. The team tested the skeleton for bacterial DNA and lipid biomarkers which are characteristic of leprosy. What they found was quite remarkable. “Not every excavation yields good quality DNA,” Professor Mike Taylor, a Bioarchaeologist from the University of Surrey, said, “but in this case, leprosy DNA isolated from the skeleton was so good it enabled us to identify its strain.” Results of the tests showed the specific lineage which the leprosy strain belonged to. The lineage, called 3I, has previously been found in burial sites from Medieval Scandinavia and southern Britain. In the case of the team’s research, the leprosy strain comes from a much earlier period, dating from the fifth or sixth Century CE. By comparing the identified fatty molecules known as lipids from the different leprosy bacteria, the team confirmed that the 3I leprosy found in the Great Chesterford skeleton was different to later strains. Isotopic analysis of the man’s teeth also provided some interesting results. It seems that the Great Chesterford man did not come from Britain; he most likely grew up elsewhere in northern Europe, perhaps southern Scandinavia. It is possible, therefore, that he brought a Scandinavian strain of the leprosy bacterium with him when he traveled to Britain. Project leader Dr Sarah Inskip of Leiden University stated: “The radiocarbon date confirms this is one of the earliest cases in the UK to have been successfully studied with modern biomolecular methods. This is exciting both for archaeologists and for microbiologists. It helps us understand the spread of disease in the past, and also the evolution of different strains of disease, which might help us fight them in the future. We plan to carry out similar studies on skeletons from different locations to build up a more complete picture of the origins and early spread of this disease.” Leprosy today is mainly confined to tropical areas, but in the past it occurred in Europe. Human migration helped to spread the disease, with skeletons from the seventh century onward in particular exhibiting signs of it. The origins of leprosy and how it spread are, however, shrouded in mystery. The recent study of the Great Chesterford skeleton has given us a fantastic opportunity to understand leprosy and, in particular, how it spread. For more information: www.journals.plosone.org Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Netha Hussain]]>

One Comment

Stephen Thake

Also picked up by New York Times but on 20th May and with less than 100 words.