<![CDATA[People with a wide range of diverse knowledge and skills are often described as “Renaissance men.” One of Europe’s great Renaissance men was actually a medieval woman, Hildegard of Bingen. Born in 1098 in Franconia (in what would later become Germany), Hildegard left her mark in mysticism, in music, in medicine and the natural sciences, and in the contentious religious and political questions of her day. Today she is remembered by music scholars, feminists, natural healers, and also devout Catholics (especially since her canonization in 2012.)

In The Beginning

Hildegard was the tenth child of a wealthy and devout family which gave her ‘as a tithe’ to the church when she was only eight years old, sending her to a Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg which had just begun to accept nuns. When she entered the monastery Hildegard had already begun to have visions which came to her surrounded by ‘a light so bright that [her] soul trembled.’ She had also figured out that other people didn’t see that light, and had decided to keep her experiences to herself—although she couldn’t conceal the physical sickness which often accompanied or followed them. Under the care of a brilliant and ascetic nun named Jutta, Hildegard learned to read and write, studied a variety of holy texts in Latin, and took holy vows when she was old enough. Jutta became Mother Superior, and on her death she chose Hildegard, who was then thirty-eight, as her successor.Coming Out

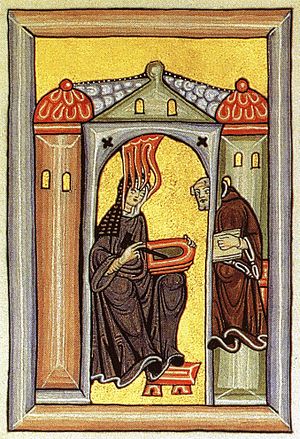

Hildegard’s administrative duties didn’t stop the visions pressing on her. She tried to keep these secret, but the effort exhausted her and finally made her seriously ill. She confided her visions to a monk who helped her record them. In the midst of her illness she heard a voice which told her to speak and write of her visions, and she obeyed, recording them as they happened and also writing long commentaries on her interpretations of those visions and the flashes of insight which accompanied them. These drew some anxious scrutiny from people higher up in the Church, but the examiners eventually decided that her visions were legitimate. The Pope wrote to Hildegard expressing his approval. Hildegard wrote back telling him to work harder to reform the Church. As the record of her visions spread far and wide, many girls and women came to study and live under Hildegard. The women’s quarters in the monastery became crowded; Hildegard may also have felt the need for more independence from the monastery’s abbot. Hildegard had absorbed her teacher Jutta’s learning, but not her asceticism; she believed in moderation, and seems to have regarded the human body with fascination rather than suspicion. Most importantly, Hildegard believed God was calling her to leave the monastery and found a new convent and church for her nuns. The abbot was very reluctant to let them go, but Hildegard persisted and finally persuaded an archbishop to overrule the abbot. She purchased land and oversaw construction of their new House at Rupertsberg near Bingen on the Rhine. Hildegard paid attention to details of the building (which included water pumped in through pipes, an unusual feature at the time) as well as administration (the nuns were free to elect their own Mother Superior without interference from the Disibodenberg monastery.) She did send part of the dowry money that had come with the nuns back to Disibodenberg. At last Hildegard had the space and freedom to pursue the physical and spiritual understandings which she prized.