Today the US government is shut down due to debates over building a wall on the border between Mexico and the US. This isn’t the first fierce political controversy over the border. Two hundred years ago all the territory where the wall might be built clearly belonged to Mexico. How did that change? The answer involves questions of sovereignty, slavery, illegal immigration, and accusations of ‘fake news.’ Today’s post describes the first part of that process.

Questions of Freedom

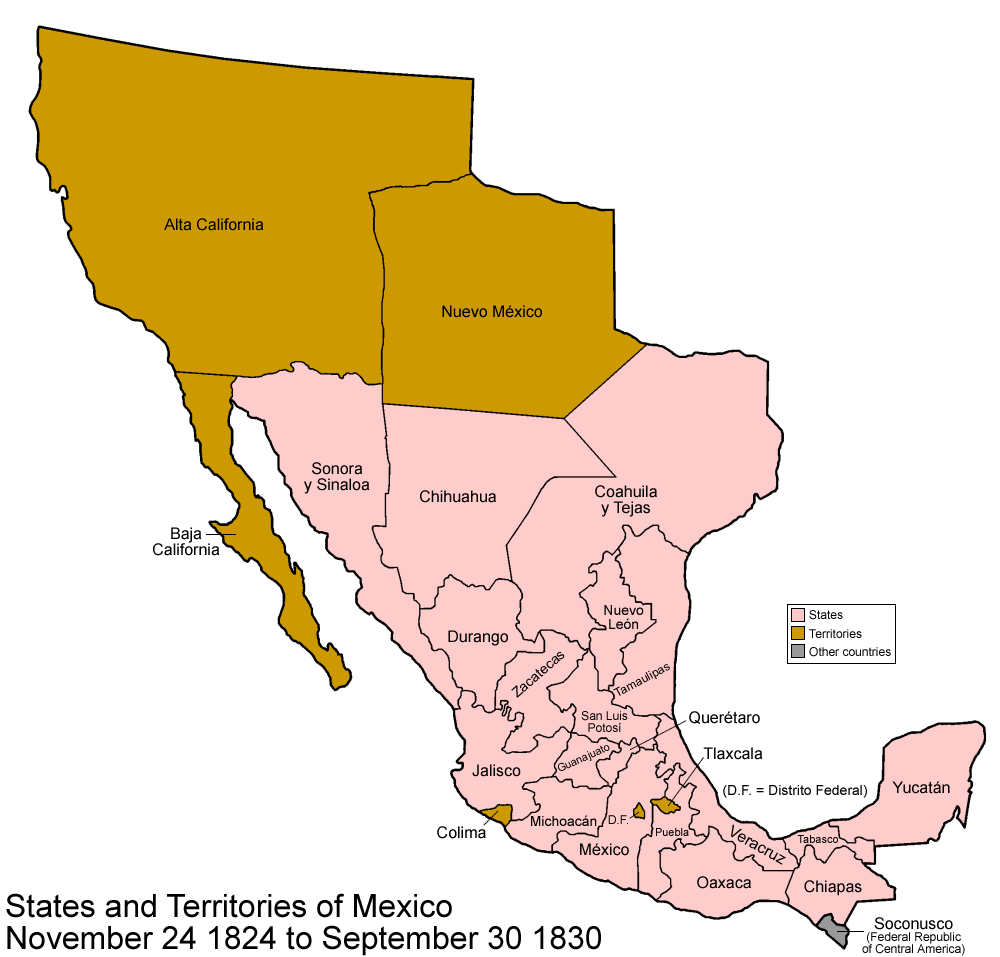

In 1820 New Spain opened some northern territories to Anglo-American settlers. Those territories, which jointly comprise today’s states of Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming, were mainly inhabited by First Nations people; Spain wanted to ‘civilize’ the land and remove or forcefully assimilate its original inhabitants. When New Spain won independence in 1821 and became Mexico, it encouraged immigrants and allowed empresarios to claim large tracts of land in exchange for bringing in large numbers of colonists “of good character” to settle on them.

One Anglo-American empresario was Stephen Austin, for whom the capital of the US state of Texas was later named. Austin was a skilled political operator who talked the new Mexican government into continuing the grant New Spain had given his family, together with tax and tariff privileges designed to encourage settlers. He preserved those privileges through the resignation of the Mexican Emperor and the subsequent political upheaval in 1823. He was far less diplomatic in his approach to the Karankawa tribe who inhabited parts of the land that had been designated as his; in 1825 he ordered Karankawas to be pursued and killed on sight. By that time 300 formerly American families had settled on the land he controlled in the combined territory of Texas/Coahuila, and had begun growing sugarcane and cotton with slave labor.

In 1829 Mexico outlawed slavery in all its territories. Austin had sometimes declared that he disapproved of slavery (in large part because he feared that slave rebellions could endanger white people), but he also knew that the economy of his colony ran on slave labor, and he wasn’t willing to lose that revenue. He lobbied successfully to get Texas exempted from the anti-slavery laws. But the Mexican government was beginning to be concerned about the influx of Protestant Anglo slaveholding immigrants who didn’t seem particularly interested in assimilating into their new country. In 1830 it banned further immigration from the US and imposed taxes and tariffs. A small group of Mexican soldiers were dispatched to prevent smuggling and illegal immigration. The American Texans, armed and irritable, didn’t take this well; at the end of the skirmishes of the 1832 Anahuac Disturbance, the Mexican army withdrew from most of its Texan garrisons, and immigrants continued to enter in large numbers. Texans began to demand separation from Coahuila and greater autonomy.

“With His Rifle, With Passports Or No Passports”

The Mexican government had more to worry about than Texas. General Santa Anna was actively rebelling against Mexico’s President. In 1833 Santa Anna took power. That same year the Texans held a Constitutional Convention, chaired by Sam Houston, a protégé of expansionist American president Andrew Jackson. That convention called for Texan separation from the territory of Coahuila, freedom from tariffs, and a repeal of the American immigration ban. Austin took the convention’s demands to Santa Anna, who repealed the immigration ban but refused the other requests. His agents intercepted Austin’s letter telling the Texans to disregard the Mexican government’s rulings, and Austin was imprisoned for eighteen months. Sam Houston left Texas and traveled through the US; some historians report that he encouraged militant immigrants to go to Texas with the view of preparing to help separate Texas from Mexico by force.

When Austin was released from prison on 1835 he wrote a letter calling for Anglo-Americans to immigrate to Texas en masse, “each man with his rifle, with passports or no passports,” and proclaimed that war was inevitable. Some historians see this as a reluctant acceptance of facts; others say he was spoiling for a fight.

At the same time, Santa Anna was moving to consolidate his power, rewrite the Mexican constitution and assert federal control over the territories. In 1835 he violently put down an insurrection in Zacatecas and prepared to assert his control in Texas. He sent 500 soldiers to Gonzalez, TX to repossess a cannon which had earlier been given to the Texans to help in their campaign against indigenous peoples. The Texans gathered in arms and refused to turn the cannon over. On October 2 they attacked the soldiers, drove them back to San Antonio and besieged them there; late in December the soldiers surrendered and were allowed to leave.

Remember the Alamo!

Santa Anna mounted a counterattack in early 1836, bringing about seven thousand troops to quell what he saw as a criminal insurrection. The Texans fortified the Alamo mission and sent out urgent appeals for other Anglos to join them. Very few came, and those who did were killed by the federal troops. Militarily, the Alamo was an unqualified defeat; but the dramatic story of the deaths of its defenders became a rallying cry for Texans. The same could be said of the capture of Texan commander James Fannin’s retreating forces and the later execution of four hundred prisoners. To these stories was added an appeal to race prejudices: Austin wrote that the inevitable conflict between a “mongrel Spanish-Indian and negro race” and “civilization and the Anglo-American race” could have only one outcome.

In March 1836 Texans formally declared their independence, and Sam Houston was put in charge of the Texan army. On April 21 his troops caught Mexican forces under Santa Anna’s command unawares, resting on the road between forts, and killed six hundred men—many of whom, according to contemporary reports, were trying to surrender. Some prisoners were taken, including Santa Anna, who signed a treaty from prison in which re recognized Texas and called off the war. The Mexican government deposed him in his absence and refused to recognize his treaty, but Texas declared victory.

Where, exactly, were the new boundaries of the Republic of Texas, and what should its relationship to the United States be? Those questions, and the lingering tensions between the Mexican government and the Texan republic, would be settled in another ten years, with complex repercussions for both the countries Texas bordered. That story will be told in next week’s column on the Mexican-American War.

]]>