Who built Stonehenge?

The questions of how and why Stonehenge was built garner significantly more research than specifically

who built it. That is partly down to the fact that many of the human remains were cremated, making it difficult to extract much useful information from them.

New technique unlocks ancient secrets

Lead author Christophe Snoeck, who is undertaking doctoral research at Oxford’s School of Archaeology, demonstrates that even cremated bone retains its strontium isotope composition, making it possible to investigate where these people had lived during the last ten years of their lives. He says: ‘The recent discovery that some biological information survives the high temperatures reached during cremation (up to 1000 degrees Celsius) offered us the exciting possibility to finally study the origin of those buried at Stonehenge.’

Professor Julia Lee-Thorp, Head of Oxford’s School of Archaeology and an author on the paper, says: ‘This new development has come about as the serendipitous result of Dr Snoeck’s interest in the effects of intense heat on bones, and our realization that that heating effectively “sealed in” some isotopic signatures.’

Stonehenge bodies travelled from Wales

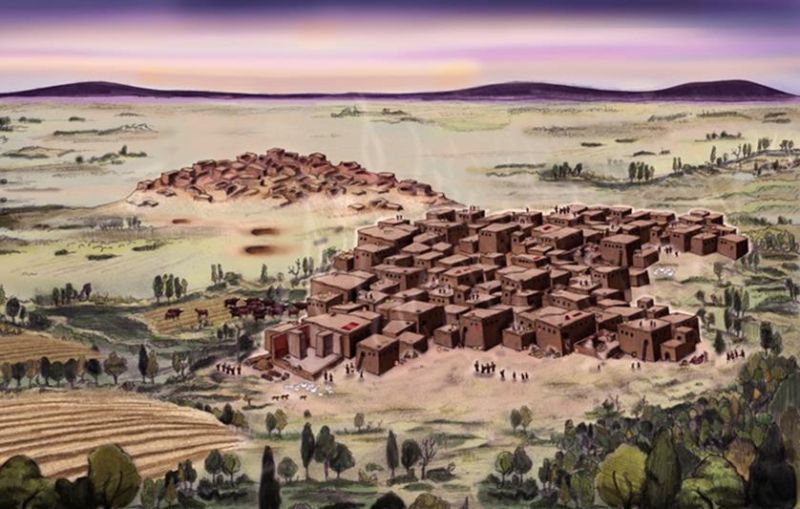

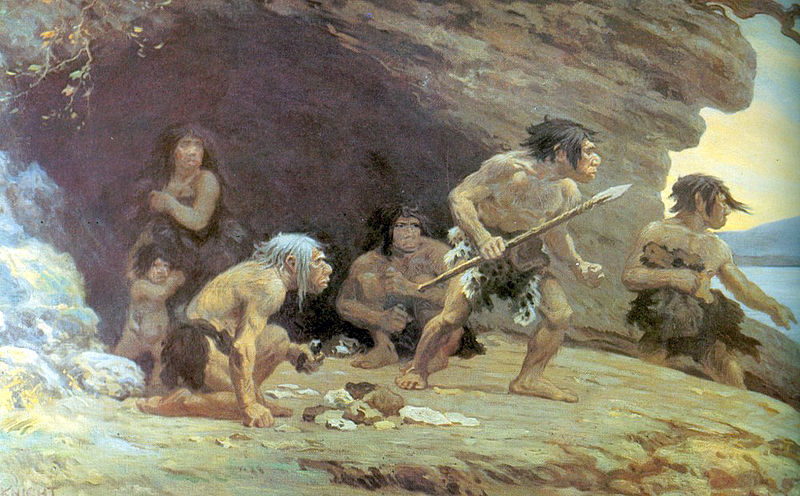

The team analysed the skulls of 25 people who were cremated at the site around 3000 BC to better understand their lives. At least ten of them did not live near Stonehenge at the time of their death. They were far more likely to have been living in western Britain; a region that includes west Wales, the known source of Stonehenge’s bluestones.

The research was conducted in partnership with colleagues from University College London, Université Libre de Bruxelles & Vrije Universiteit Brussel), and the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, France.

Rick Schulting, a lead author on the research and Associate Professor in Scientific and Prehistoric Archaeology at Oxford, explains: ‘Some of the people’s remains showed strontium isotope signals consistent with west Wales, the source of the bluestones that are now being seen as marking the earliest monumental phase of the site.’

Inter-regional connections in 3000 BC

The results emphasise the prevalence of inter-regional connections involving the movement of both materials and people in the construction and use of Stonehenge, providing rare insight into the large scale of contacts and exchanges in the Neolithic, as early as 5000 years ago.

A revolutionary analysis technique

Dr Schulting adds: ‘To me the really remarkable thing about our study is the ability of new developments in archaeological science to extract so much new information from such small and unpromising fragments of burnt bone.’

The technique is now regarded as a vehicle to improve our understanding of the past using previously excavated ancient collections.

Schulting continues: ‘Our results highlight the importance of revisiting old collections. The cremated remains from Stonehenge were first excavated by Colonel William Hawley in the 1920s, and while they were not put into a museum, Col Hawley did have the foresight to rebury them in a known location on the site, so that it was possible for Mike Parker Pearson (UCL Institute of Archaeology) and his team to re-excavate them, allowing various analytical methods to be applied.’]]>