A major climate event

Looking closely at the Neolithic and Chalcolithic city settlement of Çatalhöyük in southern Anatolia, Turkey, the study takes into account farming practices in the period spanning 7500 BC to 5700 BC.

When the city was most intensely occupied around 8,200 years ago, there was a sudden decrease in global temperatures. It became a well-documented event in the history of climate change, and was caused by a huge amount of glacial meltwater from a massive freshwater lake in northern Canada.

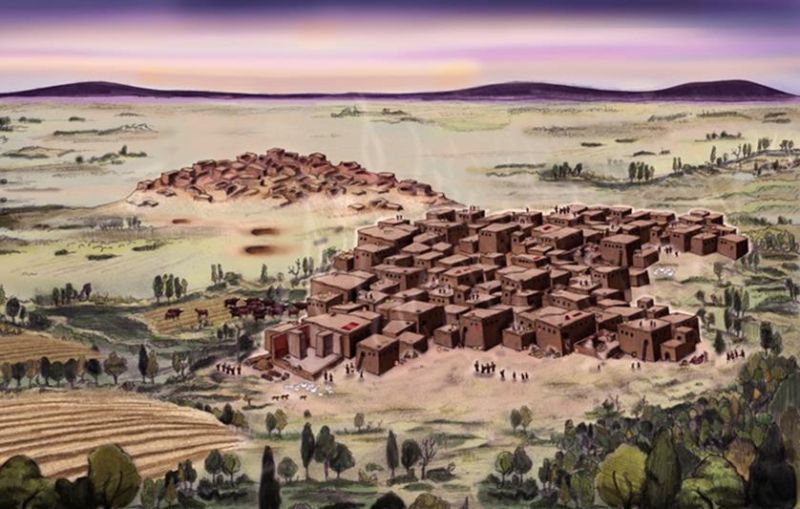

[caption id="attachment_8875" align="aligncenter" width="800"] An artist’s reconstruction of the east and west mounds at Çatalhöyük. Image Credit: Çatalhöyük Research Project[/caption]

An artist’s reconstruction of the east and west mounds at Çatalhöyük. Image Credit: Çatalhöyük Research Project[/caption]

Pragmatic farming during drought

The research centres on animal bones found at the excavation site. Scientists have concluded that the herders of the city turned towards sheep and goats, as they fared better during times of drought than cattle. By looking at the cut marks on the animal bones, we can also find more information on butchery practices. They indicate desperation in the community: the high number of cut marks on the bones during the time of the temperature drop shows how the populace exploited any meat available as food would have been scarce.Dirty dishes

Ancient cooking pots with traces of animal fats have also been analysed in the study, which makes this the first time compounds from animal fats found in pottery are shown to carry evidence for the climate event. [caption id="attachment_8874" align="aligncenter" width="500"] In situ pottery at the archaeological site of Çatalhöyük. The pottery has been at the centre of recent research shedding light on the ways ancient farming practices adapted to climate change. Image credit: Çatalhöyük Research Project.[/caption]

In situ pottery at the archaeological site of Çatalhöyük. The pottery has been at the centre of recent research shedding light on the ways ancient farming practices adapted to climate change. Image credit: Çatalhöyük Research Project.[/caption]