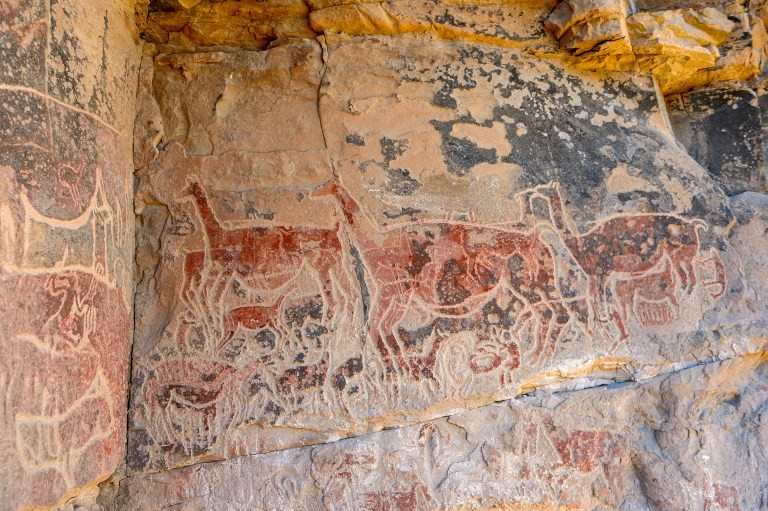

What does the Taira rock art depict?

Roughly 90% of the artworks focus on llamas. Some are pregnant, others are suckling their young; and all represent life.

The other 10% of the engravings depict the diversity of the desert, with foxes, snakes, ostriches, partridges and dogs featuring in scenes.

Human figures are few and far between, and always drawn small. Archaeologists have posited that it is as if painting them small represents just how important desert animals were to their culture and economy.

[caption id="attachment_8867" align="aligncenter" width="500"]

View of drawings at the Taira Cave in Chile, located at a height of 3,150 meters, on July 21, 2018. The paintings left by shepherds almost three millennia ago on the walls of the rocks that flank the course of the Loa River. Credit: AFP Martin Bernetti.[/caption]

The role of llamas in ancient desert culture

Archaeologist and curator at Santiago’s Museum of Pre-Colombian Art, Jose Bereguer, says that Taira art is ‘a celebration of life’. First rediscovered by Swedish archaeologist Stif Ryden in 1944, the gallery has been dated to c.400-800 BCE. 16 paintings remain, sitting 3,000 metres above sea level on the banks of the Loa River that traverses the desert. [caption id="attachment_8866" align="aligncenter" width="670"] Archaeologist Jose Bereguer, above, curator at Santiago’s Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, describes the site as “the most complex in South America” because of its astronomical importance as well as the significance to local shepherds. Credit: AFP Martin Bernetti[/caption]

Previous studies tell us that the rock art was created by shepherds, who were pleading with the ‘deities that governed the skies and the earth’ to allow their llama flocks to flourish.

The Alero Taira drawings, which were created in a natural shelter 30 metres away from the Loa River, give us deeper insight into the role of llamas in ancient desert culture.

More than just the lead source of wealth for people inhabiting the desert, the llama was a symbolic creature used in ritual ceremonies throughout the Andes for thousands of years. The ‘Wilancha’, for instance, sees llamas given as sacrifice to ‘Pacha Mama’ (Mother Earth). Volcanoes, like springs, were considered deities by the Atacama natives, while llamas were thought to have been born of springs.

Berenguer says: “No one can understand the things done 18,000 years ago because the cultures that did them have disappeared. Here, it’s possible to delve into the meaning because we have ethnography and because there are still people living in practically the same way as in the past.”

Archaeologist Jose Bereguer, above, curator at Santiago’s Museum of Pre-Columbian Art, describes the site as “the most complex in South America” because of its astronomical importance as well as the significance to local shepherds. Credit: AFP Martin Bernetti[/caption]

Previous studies tell us that the rock art was created by shepherds, who were pleading with the ‘deities that governed the skies and the earth’ to allow their llama flocks to flourish.

The Alero Taira drawings, which were created in a natural shelter 30 metres away from the Loa River, give us deeper insight into the role of llamas in ancient desert culture.

More than just the lead source of wealth for people inhabiting the desert, the llama was a symbolic creature used in ritual ceremonies throughout the Andes for thousands of years. The ‘Wilancha’, for instance, sees llamas given as sacrifice to ‘Pacha Mama’ (Mother Earth). Volcanoes, like springs, were considered deities by the Atacama natives, while llamas were thought to have been born of springs.

Berenguer says: “No one can understand the things done 18,000 years ago because the cultures that did them have disappeared. Here, it’s possible to delve into the meaning because we have ethnography and because there are still people living in practically the same way as in the past.”