Mass Grave Could be Viking Army Burial

A mass grave discovered in the 1980s could be a burial site for the war dead of the Viking Great Army, according to new research.

Initial excavations at the site at St Wystan’s Church in Repton, Derbyshire, UK unearthed several Viking graves and a charnel deposit of nearly 300 people underneath a shallow mound in the vicarage garden.

Later radiocarbon dating seemed to suggest that the grave consisted of bones collected over several centuries, throwing doubt on whether it was a mass Viking burial. However, the new scientific research, led by Cat Jarman from the University of Bristol, shows that in fact all the bones are consistent with a date in the late ninth century.

The mound appears to have been a burial monument linked to the Great Viking Army. According to historical records, the Great Viking Army wintered in Repton in 873 CE, driving the Mercian king into exile.

One room of the burial site was packed with the remains of a minimum of 264 people, around 20% of whom were women. Viking weapons and artefacts were found among the remains, including knives, axes and pennies. Mostly aged between 18 and 45 when they died, several of the male sets of remains showed signs of violent trauma.

Jarman and team re-dated the remains, showing that contrary to what the previous carbon dating had suggested, the remains were all consistent with a single date in the ninth century, and the Great Viking Army.

Jarman said: “The previous radiocarbon dates from this site were all affected by something called marine reservoir effects, which is what made them seem too old.

“When we eat fish or other marine foods, we incorporate carbon into our bones that is much older than in terrestrial foods. This confuses radiocarbon dates from archaeological bone material and we need to correct for it by estimating how much seafood each individual ate.”

The study has been published in the journal Antiquity. According to Jarman, the research could be a starting point for learning more about the Great Viking Army.

“The date of the Repton charnel bones is important because we know very little about the first Viking raiders that went on to become part of considerable Scandinavian settlement of England.

“Although these new radiocarbon dates don’t prove that these were Viking army members it now seems very likely. It also shows how new techniques can be used to reassess and finally solve centuries old mysteries.”

Prehistoric Weapons Recreated

Archaeologists from the University of Washington have recreated the weapons used by hunter-gatherers in the post-Ice Age Arctic up to 14,000 years ago.

Janice Wood, a recent anthropology graduate, and Ben Fitzhugh, a professor of anthropology, reconstructed projectiles and points from ancient sites in what is now Alaska, and studied the qualities that made them effective hunting weapons.

Their study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, focused on hunting weapons from the earliest archaeological records of Alaska (10,000 to 14,000 years ago), when a range of different projectiles and points were in use. Their study has provided insights into the technological choices made by prehistoric Alaskans.

“The hunter-gatherers of 12,000 years ago were more sophisticated than we give them credit for,” Fitzhugh said. “We haven’t thought of hunter-gatherers in the Pleistocene as having that kind of sophistication, but they clearly did for the things that they had to manage in their daily lives, such as hunting game. They had a very comprehensive understanding of different tools, and the best tools for different prey and shot conditions.”

Wood travelled to the area around Fairbanks, Alaska, and crafted 30 projectile points of various kinds, staying as close to the original materials and manufacturing processes as possible. Projectiles were made from poplar, with birch tar used as an adhesive to affix the points to the tips of the projectiles.

The anthropologist then tested how well each point could penetrate and damage two different targets: blocks of ballistic gelatin (a synthetic gelatin meant to mimic animal muscle tissue), and a fresh reindeer carcass purchased from a local farm. Instead of an atlatl, a kind of throwing board used by ancient Alaskans, Wood used a maple recurve bow to shoot the arrows.

Three different types of point were tested: composite microblades, stone and bone. It was found that the microblades were more effective on smaller prey, due to their versatility and ability to inflict more damage. The bone points penetrated more deeply and created narrower wounds, suggesting they could be used to stun larger prey such as bison. The stone points could have cut wider wounds, especially on larger prey, resulting in quicker kills.

Jarman and team re-dated the remains, showing that contrary to what the previous carbon dating had suggested, the remains were all consistent with a single date in the ninth century, and the Great Viking Army.

Jarman said: “The previous radiocarbon dates from this site were all affected by something called marine reservoir effects, which is what made them seem too old.

“When we eat fish or other marine foods, we incorporate carbon into our bones that is much older than in terrestrial foods. This confuses radiocarbon dates from archaeological bone material and we need to correct for it by estimating how much seafood each individual ate.”

The study has been published in the journal Antiquity. According to Jarman, the research could be a starting point for learning more about the Great Viking Army.

“The date of the Repton charnel bones is important because we know very little about the first Viking raiders that went on to become part of considerable Scandinavian settlement of England.

“Although these new radiocarbon dates don’t prove that these were Viking army members it now seems very likely. It also shows how new techniques can be used to reassess and finally solve centuries old mysteries.”

Prehistoric Weapons Recreated

Archaeologists from the University of Washington have recreated the weapons used by hunter-gatherers in the post-Ice Age Arctic up to 14,000 years ago.

Janice Wood, a recent anthropology graduate, and Ben Fitzhugh, a professor of anthropology, reconstructed projectiles and points from ancient sites in what is now Alaska, and studied the qualities that made them effective hunting weapons.

Their study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, focused on hunting weapons from the earliest archaeological records of Alaska (10,000 to 14,000 years ago), when a range of different projectiles and points were in use. Their study has provided insights into the technological choices made by prehistoric Alaskans.

“The hunter-gatherers of 12,000 years ago were more sophisticated than we give them credit for,” Fitzhugh said. “We haven’t thought of hunter-gatherers in the Pleistocene as having that kind of sophistication, but they clearly did for the things that they had to manage in their daily lives, such as hunting game. They had a very comprehensive understanding of different tools, and the best tools for different prey and shot conditions.”

Wood travelled to the area around Fairbanks, Alaska, and crafted 30 projectile points of various kinds, staying as close to the original materials and manufacturing processes as possible. Projectiles were made from poplar, with birch tar used as an adhesive to affix the points to the tips of the projectiles.

The anthropologist then tested how well each point could penetrate and damage two different targets: blocks of ballistic gelatin (a synthetic gelatin meant to mimic animal muscle tissue), and a fresh reindeer carcass purchased from a local farm. Instead of an atlatl, a kind of throwing board used by ancient Alaskans, Wood used a maple recurve bow to shoot the arrows.

Three different types of point were tested: composite microblades, stone and bone. It was found that the microblades were more effective on smaller prey, due to their versatility and ability to inflict more damage. The bone points penetrated more deeply and created narrower wounds, suggesting they could be used to stun larger prey such as bison. The stone points could have cut wider wounds, especially on larger prey, resulting in quicker kills. For Wood, these findings show that the hunter-gatherers were sophisticated enough to recognise which points to use and when.

“We have shown how each point has its own performance strengths. It has to do with the animal itself; animals react differently to different wounds. And it would have been important to these nomadic hunters to bring the animal down efficiently. They were hunting for food.”

The authors believe that the research could also shed new light on debates over whether human hunting practices could have led to the extinction of certain species.

“I see this line of research as looking at the capacity of the human brain to come up with innovations that ultimately changed the course of human history,” she said. “This reveals the human capacity to invent in extreme circumstances, to figure out a need and a way to meet that need that made it easier to eat and minimised the risk.”

History of Dice Revealed in New Study

New research has charted the history and development of dice, revealing how they’ve changed over the last 2,000 years to become unbiased, with every number having an equal probability of being rolled.

The research was led by Jelmer Eerkens, professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis. It reveals that in the Roman era, many dice were lopsided, in contrast to the perfect cubes seen today. It also highlights that Roman dice varied drastically in shape, size, material and the configuration of numbers.

Between 400 CE and 1100 CE, dice are apparently extremely rare in the archaeological record, corresponding with the Dark Ages.

According to Eerkens and colleagues’ research, a new awareness of the importance of form in dice became apparent around 1450, reflecting the onset of the Renaissance.

“A new worldview was emerging — the Renaissance. People like Galileo and Blaise Pascal were developing ideas about chance and probability, and we know from written records in some cases they were actually consulting with gamblers,” he said. “We think users of dice also adopted new ideas about fairness, and chance or probability in games.”

“Standardising the attributes of a die, like symmetry and the arrangement of numbers, may have been one method to decrease the likelihood that an unscrupulous player had manipulated the dice to change the odds of a particular roll,” Eerkens continued.

Eerkens and his co-author, Alex de Voogt of the American Museum of Natural History, looked at hundreds of dice in museums and archaeological depots across the Netherlands, assembling a set of 110 carefully dated, cube shaped dice to analyse.

For Eerkens, dice present a fascinating artefact for archaeologists, embodying shifting worldviews.

“In this case, we believe it follows changing ideas about chance and fate.”

The study has been published in the journal Acta Archaeologica.

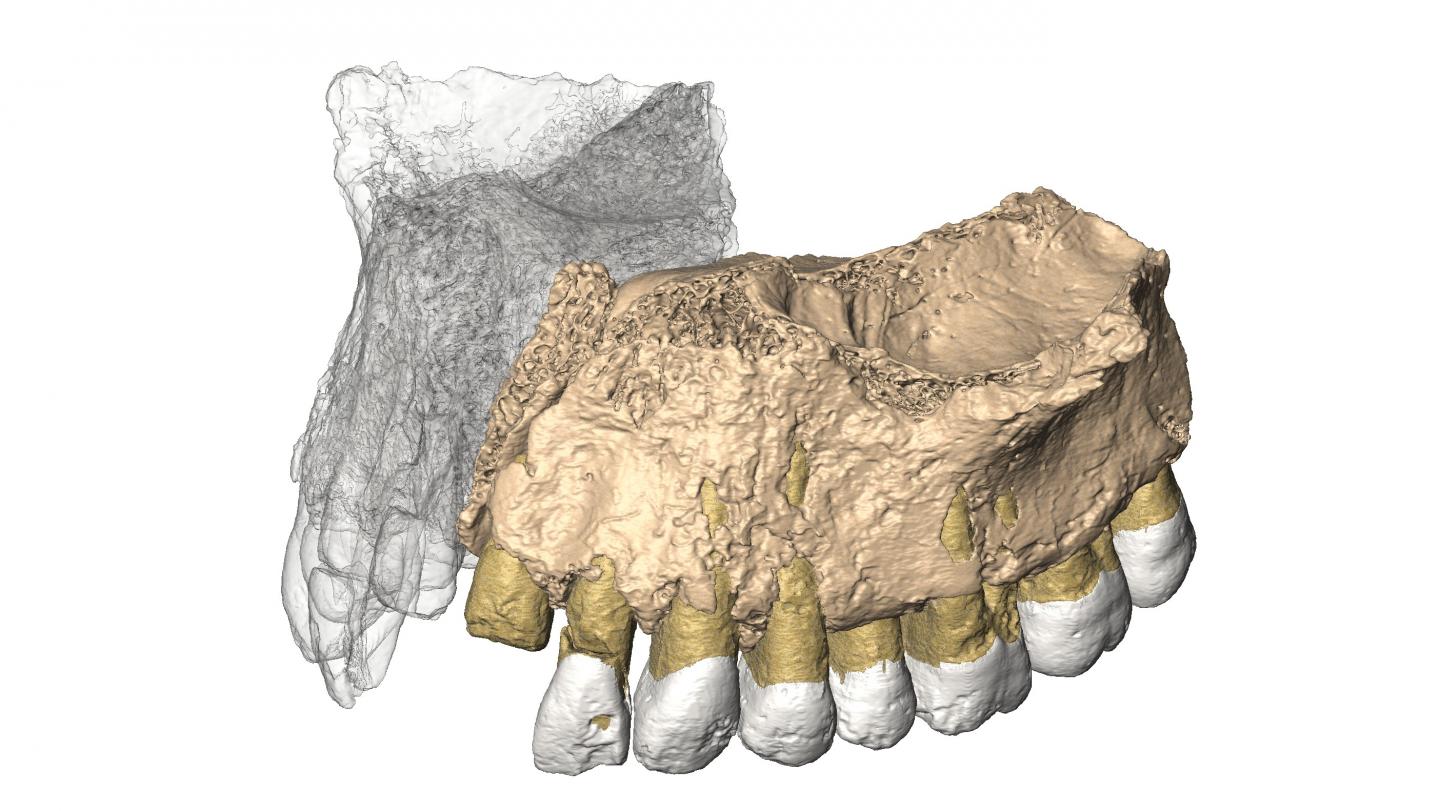

Featured image is one of the female skulls from the Repton charnel. Image credit: Cat Jarman]]>

For Wood, these findings show that the hunter-gatherers were sophisticated enough to recognise which points to use and when.

“We have shown how each point has its own performance strengths. It has to do with the animal itself; animals react differently to different wounds. And it would have been important to these nomadic hunters to bring the animal down efficiently. They were hunting for food.”

The authors believe that the research could also shed new light on debates over whether human hunting practices could have led to the extinction of certain species.

“I see this line of research as looking at the capacity of the human brain to come up with innovations that ultimately changed the course of human history,” she said. “This reveals the human capacity to invent in extreme circumstances, to figure out a need and a way to meet that need that made it easier to eat and minimised the risk.”

History of Dice Revealed in New Study

New research has charted the history and development of dice, revealing how they’ve changed over the last 2,000 years to become unbiased, with every number having an equal probability of being rolled.

The research was led by Jelmer Eerkens, professor of anthropology at the University of California, Davis. It reveals that in the Roman era, many dice were lopsided, in contrast to the perfect cubes seen today. It also highlights that Roman dice varied drastically in shape, size, material and the configuration of numbers.

Between 400 CE and 1100 CE, dice are apparently extremely rare in the archaeological record, corresponding with the Dark Ages.

According to Eerkens and colleagues’ research, a new awareness of the importance of form in dice became apparent around 1450, reflecting the onset of the Renaissance.

“A new worldview was emerging — the Renaissance. People like Galileo and Blaise Pascal were developing ideas about chance and probability, and we know from written records in some cases they were actually consulting with gamblers,” he said. “We think users of dice also adopted new ideas about fairness, and chance or probability in games.”

“Standardising the attributes of a die, like symmetry and the arrangement of numbers, may have been one method to decrease the likelihood that an unscrupulous player had manipulated the dice to change the odds of a particular roll,” Eerkens continued.

Eerkens and his co-author, Alex de Voogt of the American Museum of Natural History, looked at hundreds of dice in museums and archaeological depots across the Netherlands, assembling a set of 110 carefully dated, cube shaped dice to analyse.

For Eerkens, dice present a fascinating artefact for archaeologists, embodying shifting worldviews.

“In this case, we believe it follows changing ideas about chance and fate.”

The study has been published in the journal Acta Archaeologica.

Featured image is one of the female skulls from the Repton charnel. Image credit: Cat Jarman]]>