Mystery of Mummified Brothers solved

Modern DNA techniques have solved a 4,000-year-old mummy mystery.

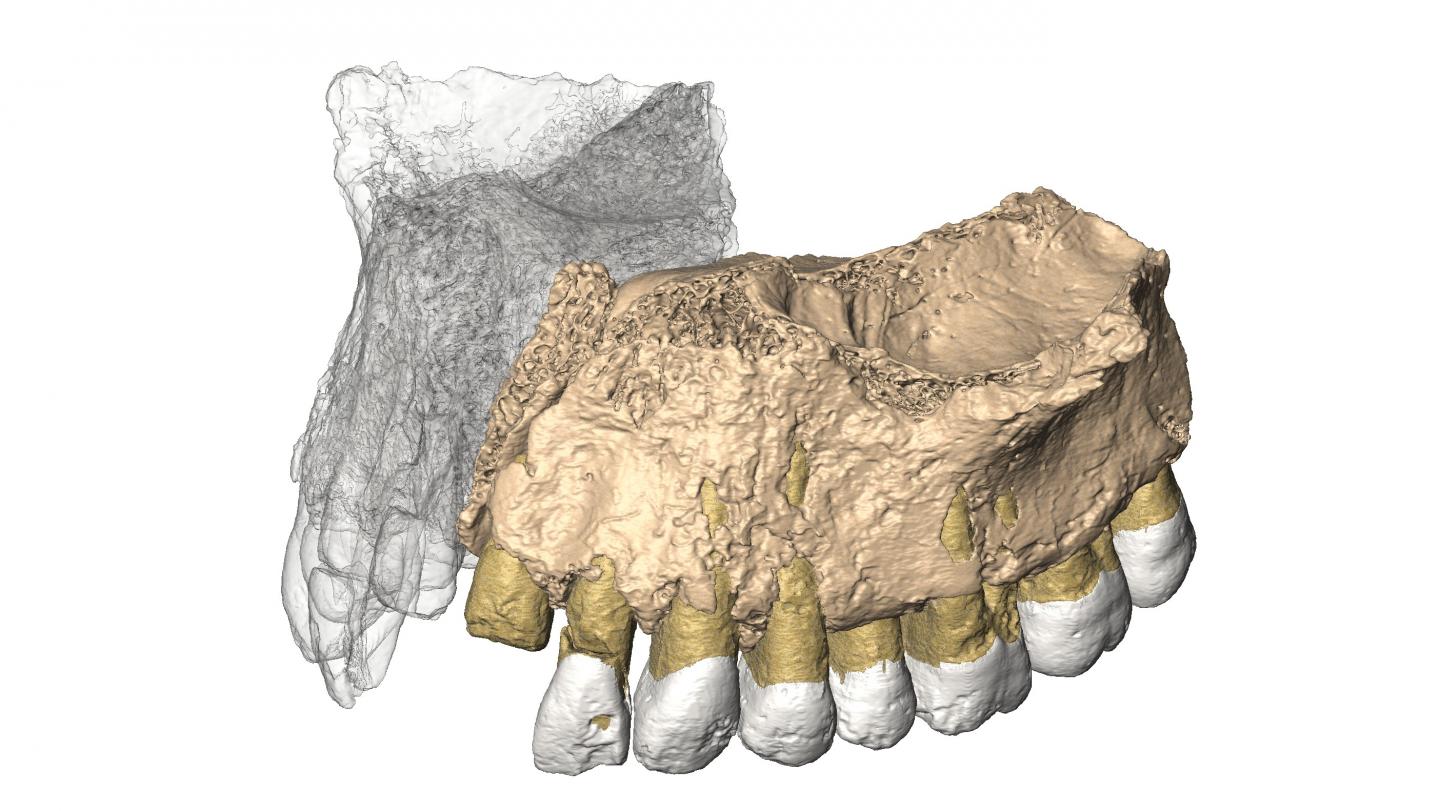

For years, two mummies at the Manchester Museum were thought to be brothers, but a new study by scientists from the University of Manchester has revealed they are in fact half-brothers with a different father.

The mummies are of two ancient Egyptian elites, Khnum-nakht and Nakht-ankh – dating to around 1800 BCE. Despite popularly being dubbed ‘The Two Brothers’, ever since their discovery in 1907 there has been debate over whether they were really related.

Hieroglyphic inscriptions on their coffins had suggested the two men were siblings. However, when pioneering Egyptologist Dr. Margaret Murray unwrapped the two mummies in 1908, she argued that differences in skeletal morphologies suggested they weren’t actually related and one had been adopted.

In 2015, DNA was extracted from the teeth and sequenced using a next generation technique to determine the relationship – if any – of the two men. The results have now been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, revealing that they were half-brothers.

Dr Konstantina Drosou, of the School of Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Manchester, who conducted the DNA sequencing, said: “It was a long and exhausting journey to the results but we are finally here. I am very grateful we were able to add a small but very important piece to the big history puzzle and I am sure the brothers would be very proud of us. These moments are what make us believe in ancient DNA. ”

The study is the first to successfully use the typing of both mitochondrial and Y chromosomal DNA in Egyptian mummies.

Europe’s Forests Halved over last 6,000 years

More than 50% of Europe’s forests have disappeared in the last 6,000 years, new research claims. Authors of the new study identify the need for agricultural land and wood as a source of fuel as causing the massive deforestation.

The shocking findings were made through pollen analysis at over 1,000 different sites on the continent. They reveal that at one point more than two thirds of northern and central Europe were covered by trees. By contrast, now only a third of the region is covered with forest. In the UK, Ireland and other coastal areas, the amount has plummeted to less than 10%.

Published in the journal Scientific Reports, the study points out that this trend of massive deforestation is now starting to reverse due to new types of fuel and building techniques, and ecological initiatives.

“Most countries go through a forest transition and the UK and Ireland reached their forest minimum around 200 years ago,” said study lead author Neil Roberts, Professor of Physical Geography at the University of Plymouth.

“Other countries in Europe have yet to reach that point, and some parts of Scandinavia – where there is not such a reliance on agriculture – are still predominantly forest. But generally, forest loss has been a dominant feature of Europe’s landscape ecology in the second half of the current interglacial, with consequences for carbon cycling, ecosystem functioning and biodiversity.”

Along with Roberts, the study also involved scientists from Estonia, France, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Remarkably, in their bid to track the development of Europe’s forests over the last 11,000 years, the authors found that between 11,000 and 6,000 years ago the amount of forest coverage increased, from 60& to 80%.

The introduction of ‘modern’ farming practices in the Neolithic period started the drastic decline that accelerated towards the end of the Bronze Age and has lasted until the present.

Glass Was Made in Sub-Saharan Africa Centuries Before Europeans Arrived

Glass was being made in Sub-Saharan Africa centuries before the arrival of Europeans, new research has discovered.

Scientists from Rice University, University College London and the Field Museum say the findings represent a new chapter in the history of glass making.

Abidemi Babatunde Babalola, a recent graduate of Rice with a PhD in anthropology and a visiting fellow at Harvard University, came across evidence of early glass making during archaeological excavations at Igbo Olokun, located on the northern periphery of Ile-Ife in southwestern Nigeria. He recovered more than 12,000 glass beads and several kilograms of glass-working debris.

“This area has been recognised as a glass-working workshop for more than a century,” Babalola said. “The glass-encrusted containers and beads that have been uncovered there were viewed for many years as evidence that imported glass was remelted and reworked.”

A decade ago, it was found that the chemical composition of the glass from Ile-Ife was different to other known glass production areas, raising the possibility the glass was actually produced in Ile-Ife.

The excavations at Igbo Olokun have confirmed that possibility. The researchers analysed 52 of the glass beads discovered, revealing that none matched the chemical composition of any glass production area in the ‘Old World’. The excavations revealed that glass production at Igbo Olokun dates to the eleventh through fifteenth centuries CE, long before Europeans arrived at the west coast of Africa.

The teams’ findings have been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Featured Image: The Two Brothers are the Museum’s oldest mummies and amongst the best-known human remains in its Egyptology collection. They are the mummies of two elite men — Khnum-nakht and Nakht-ankh — dating to around 1800 BCE. Credit: Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester]]>

Europe’s Forests Halved over last 6,000 years

More than 50% of Europe’s forests have disappeared in the last 6,000 years, new research claims. Authors of the new study identify the need for agricultural land and wood as a source of fuel as causing the massive deforestation.

The shocking findings were made through pollen analysis at over 1,000 different sites on the continent. They reveal that at one point more than two thirds of northern and central Europe were covered by trees. By contrast, now only a third of the region is covered with forest. In the UK, Ireland and other coastal areas, the amount has plummeted to less than 10%.

Published in the journal Scientific Reports, the study points out that this trend of massive deforestation is now starting to reverse due to new types of fuel and building techniques, and ecological initiatives.

“Most countries go through a forest transition and the UK and Ireland reached their forest minimum around 200 years ago,” said study lead author Neil Roberts, Professor of Physical Geography at the University of Plymouth.

“Other countries in Europe have yet to reach that point, and some parts of Scandinavia – where there is not such a reliance on agriculture – are still predominantly forest. But generally, forest loss has been a dominant feature of Europe’s landscape ecology in the second half of the current interglacial, with consequences for carbon cycling, ecosystem functioning and biodiversity.”

Along with Roberts, the study also involved scientists from Estonia, France, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. Remarkably, in their bid to track the development of Europe’s forests over the last 11,000 years, the authors found that between 11,000 and 6,000 years ago the amount of forest coverage increased, from 60& to 80%.

The introduction of ‘modern’ farming practices in the Neolithic period started the drastic decline that accelerated towards the end of the Bronze Age and has lasted until the present.

Glass Was Made in Sub-Saharan Africa Centuries Before Europeans Arrived

Glass was being made in Sub-Saharan Africa centuries before the arrival of Europeans, new research has discovered.

Scientists from Rice University, University College London and the Field Museum say the findings represent a new chapter in the history of glass making.

Abidemi Babatunde Babalola, a recent graduate of Rice with a PhD in anthropology and a visiting fellow at Harvard University, came across evidence of early glass making during archaeological excavations at Igbo Olokun, located on the northern periphery of Ile-Ife in southwestern Nigeria. He recovered more than 12,000 glass beads and several kilograms of glass-working debris.

“This area has been recognised as a glass-working workshop for more than a century,” Babalola said. “The glass-encrusted containers and beads that have been uncovered there were viewed for many years as evidence that imported glass was remelted and reworked.”

A decade ago, it was found that the chemical composition of the glass from Ile-Ife was different to other known glass production areas, raising the possibility the glass was actually produced in Ile-Ife.

The excavations at Igbo Olokun have confirmed that possibility. The researchers analysed 52 of the glass beads discovered, revealing that none matched the chemical composition of any glass production area in the ‘Old World’. The excavations revealed that glass production at Igbo Olokun dates to the eleventh through fifteenth centuries CE, long before Europeans arrived at the west coast of Africa.

The teams’ findings have been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Featured Image: The Two Brothers are the Museum’s oldest mummies and amongst the best-known human remains in its Egyptology collection. They are the mummies of two elite men — Khnum-nakht and Nakht-ankh — dating to around 1800 BCE. Credit: Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester]]>