Cheops Pyramid Void an Iron Throne Room?

An Italian archaeologist has come up with a theory for the huge void recently discovered in the Cheops (Khufu) Pyramid.

In November 2017, the results of the Scan Pyramids project were published in the journal Nature. They revealed a huge void measuring at least thirty metres long within the Pyramid of Cheops. The project used a non-invasive technique based on the measurement of muons: elementary particles that are generated in cosmic rays and absorbed differently depending on the materials they go through.

Giulio Magli, Director of the Department of Mathematics and Professor of Archaeoastronomy at the Politecnico di Milano, has now come up with a possible explanation for the mysterious void, suggesting it could be a Pharaoh’s “iron throne”.

“Cheops Pyramid, built around 2550 BC, is one of the largest and most complex monuments in the history of architecture. Its internal rooms are accessible through narrow tunnels, one of which, before arriving at the funerary chamber, widens and rises suddenly forming the so-called Great Gallery,” Magli explained in a press release.

“The newly discovered room is over this gallery, but does not have a practical function of “relieving weight ” from it, because the roof of the gallery itself was already built with a corbelled technique for this very reason.”

Magli continued: “There is a possible interpretation, which is in good agreement with what we know about the Egyptian funerary religion as witnessed in the Pyramids Texts. In these texts it is said that the pharaoh, before reaching the stars of the north, will have to pass the “gates of the sky” and sit on his “throne of iron”.

It would be possible to check Magli’s hypothesis by exploring the north shaft of the Cheops Pyramid. At present, it’s not known for sure that the north shaft leads into the mysterious void, as the available images are only approximations of the pyramid’s layout.

Dual Migration Routes to Scandinavia Suggested by new Genomic Data

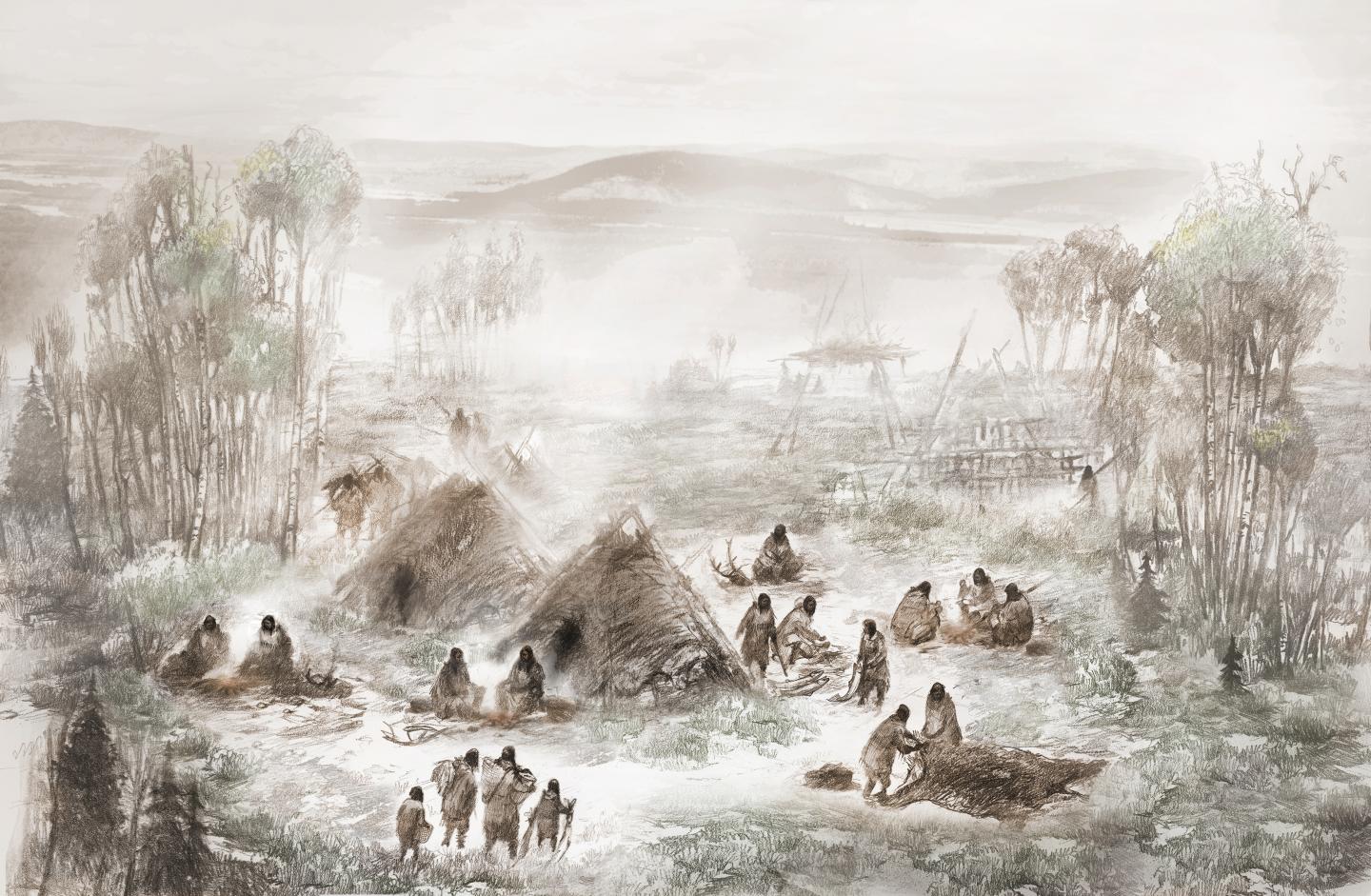

The first human settlers to Scandinavia arrived by two distinct migration routes, new research suggests. The new study, which has been published in the journal PLOS Biology, also suggests that the resulting mixed population genetically adapted to the extreme environmental conditions.

Although there is consistent evidence of a human presence in the Scandinavian peninsula from around 11,700 years ago, the migration routes and genetic makeup of the first Scandinavians have until now remained elusive.

Researchers from Uppsala University sequenced the genomes of seven hunter-gatherers excavated from across Scandinavia and dated to be between 9,500 to 6,000 years old. They determined from their findings that migrations into Scandinavia likely followed two routes, one from central Europe and one from the Northeast along the Norwegian Atlantic Coast.

The two groups met and mixed in Scandinavia, creating a genetically diverse population with variants that haven’t been passed along to modern Europeans.

Several genetic variants in the hunter-gatherers were found to be linked to a gene associated with physical performance. The study authors hypothesise that this could be part of the physical adaption to cold weather. In addition, the hunter-gatherers had a high-frequency of genetic variants linked to reduced skin pigmentation, a known adaptation to environments with low UV radiation, such as those at high latitude.

“We used cutting-edge genomic approaches to investigate hypotheses about the early colonization of northern Europe after the ice-sheet of the last glaciation retracted. It is really great to see how evidence from different disciplines can be combined to understand these complex past demographic processes,” said population geneticist Torsten Günther, one of the lead authors, in a press release.

Council Accused of Covering Up Major Archaeological Find

North Somerset Council in the UK has been accused of trying to keep a major archaeological find quiet, according to the BBC.

The pre-Christian cemetery, containing over 300 graves, was discovered in the village of Yatton in 2017, during works to develop the land for housing. Some have claimed that the local council attempted to keep the find “hush-hush”, although the council told the BBC that publicising cemetery excavations was not common practice.

“I’m amazed there hasn’t been more public communication between the archaeologists, the developer and the local community – it’s almost scandalous,” Mark Horton, professor of archaeology at the University of Bristol, told the BBC.

“It’s normal procedure – even if the public aren’t allowed inside – to put information on the outside about what’s been found and it does seem to be really bad practice that there’s such secrecy about this project.”

The remarkable site is close to both an Iron Age fort and a Roman hill fort.

An archaeologist for the council claimed that the fact human remains were found at the site meant that information about it was not made widely available to the public.

“It seems like we’ve been covering it up, but it’s common practice not to publicise the excavation of cemeteries like this to avoid risking the integrity of the site,” said Cat Lodge, archaeologist for the council.

Boor Homes, the company developing the site, said in a statement to the BBC that “no identified grave goods” or “datable artefacts” had been unearthed, while the skeletons “are in varying states of survival”.

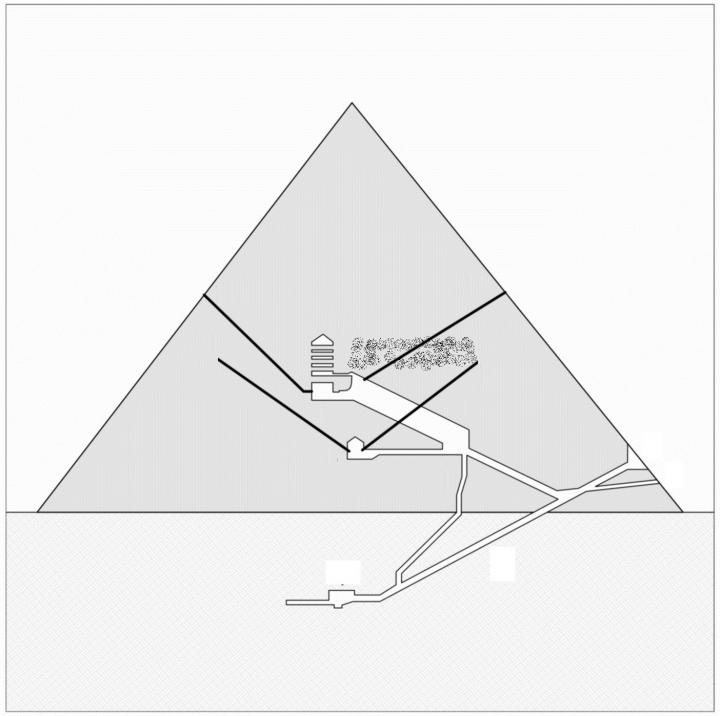

Featured image: North-south section of the Great Pyramid showing (dust-filled area) the hypothetical project of the chamber, in connection with the lower southern shaft. The upper southern shaft does not intersects the chamber (as instead suggested by the section) because, when viewed in plan, it is displaced to the west with respect to the Great Gallery. Courtesy of Giulio Magli]]>

Dual Migration Routes to Scandinavia Suggested by new Genomic Data

The first human settlers to Scandinavia arrived by two distinct migration routes, new research suggests. The new study, which has been published in the journal PLOS Biology, also suggests that the resulting mixed population genetically adapted to the extreme environmental conditions.

Although there is consistent evidence of a human presence in the Scandinavian peninsula from around 11,700 years ago, the migration routes and genetic makeup of the first Scandinavians have until now remained elusive.

Researchers from Uppsala University sequenced the genomes of seven hunter-gatherers excavated from across Scandinavia and dated to be between 9,500 to 6,000 years old. They determined from their findings that migrations into Scandinavia likely followed two routes, one from central Europe and one from the Northeast along the Norwegian Atlantic Coast.

The two groups met and mixed in Scandinavia, creating a genetically diverse population with variants that haven’t been passed along to modern Europeans.

Several genetic variants in the hunter-gatherers were found to be linked to a gene associated with physical performance. The study authors hypothesise that this could be part of the physical adaption to cold weather. In addition, the hunter-gatherers had a high-frequency of genetic variants linked to reduced skin pigmentation, a known adaptation to environments with low UV radiation, such as those at high latitude.

“We used cutting-edge genomic approaches to investigate hypotheses about the early colonization of northern Europe after the ice-sheet of the last glaciation retracted. It is really great to see how evidence from different disciplines can be combined to understand these complex past demographic processes,” said population geneticist Torsten Günther, one of the lead authors, in a press release.

Council Accused of Covering Up Major Archaeological Find

North Somerset Council in the UK has been accused of trying to keep a major archaeological find quiet, according to the BBC.

The pre-Christian cemetery, containing over 300 graves, was discovered in the village of Yatton in 2017, during works to develop the land for housing. Some have claimed that the local council attempted to keep the find “hush-hush”, although the council told the BBC that publicising cemetery excavations was not common practice.

“I’m amazed there hasn’t been more public communication between the archaeologists, the developer and the local community – it’s almost scandalous,” Mark Horton, professor of archaeology at the University of Bristol, told the BBC.

“It’s normal procedure – even if the public aren’t allowed inside – to put information on the outside about what’s been found and it does seem to be really bad practice that there’s such secrecy about this project.”

The remarkable site is close to both an Iron Age fort and a Roman hill fort.

An archaeologist for the council claimed that the fact human remains were found at the site meant that information about it was not made widely available to the public.

“It seems like we’ve been covering it up, but it’s common practice not to publicise the excavation of cemeteries like this to avoid risking the integrity of the site,” said Cat Lodge, archaeologist for the council.

Boor Homes, the company developing the site, said in a statement to the BBC that “no identified grave goods” or “datable artefacts” had been unearthed, while the skeletons “are in varying states of survival”.

Featured image: North-south section of the Great Pyramid showing (dust-filled area) the hypothetical project of the chamber, in connection with the lower southern shaft. The upper southern shaft does not intersects the chamber (as instead suggested by the section) because, when viewed in plan, it is displaced to the west with respect to the Great Gallery. Courtesy of Giulio Magli]]>