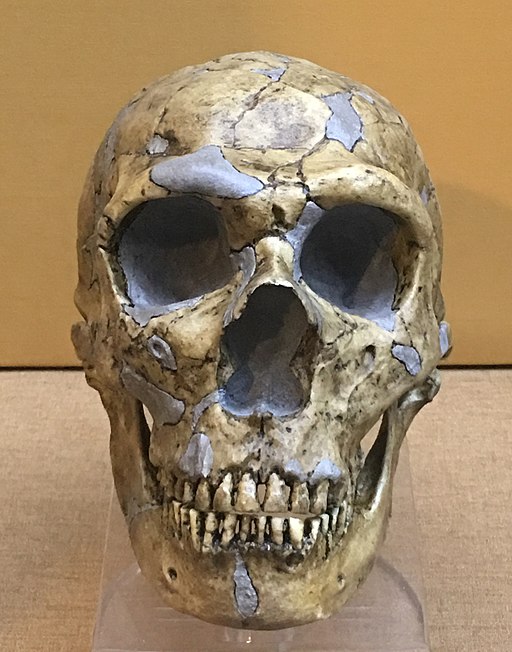

Neanderthals Were Always Doomed A new study, published this week in the journal Nature Communications, claims the Neanderthals were doomed the moment humans entered Eurasia. Scientists have long been trying to determine the cause of the Neanderthals’ extinction. Theories have ranged from the spread of humans providing too much resource competition for the Neanderthals’ to survive, to climate change or fundamental genetic limitations. The latest study suggests that the Neanderthals’ fate was inevitable. The Stamford University scientists used computer modelling to show that the migration of modern humans from Africa into Asia meant humans were always going to eventually replace Neanderthals, whatever factors might have played a role in the species’ collapse. “Here we show that a scenario of migration and selectively neutral species drift predicts the Neanderthals’ replacement,” the authors write in the introduction to their study. Neanderthals inhabited Eurasia for over 300,000 years, yet within 15,000 years of the arrival of modern humans to the region, our closest extinct living relatives were extinct. “We suggest that although selection and environmental factors may or may not have played a role in the inter-species dynamics of Neanderthals and modern humans, the eventual replacement of the Neanderthals was determined by the repeated migration of modern humans from Africa into Eurasia,” the authors write. “Our simple model suggests that recurring migration from Africa into the Levant and Europe—even at a low rate—was sufficient to result in the Neanderthals’ replacement even if neither species had a selective advantage over the other, and regardless of possible differences in population size between the two species.” Fossils of Humans’ Oldest Ancestors Discovered in Southern England Fossils of the oldest mammals from the line that led to mankind have been discovered on England’s Jurassic Coast. The small, rat like mammals lived 145 million years ago, at the time of the dinosaurs, and are the ancestors of most mammals alive today – from humans to blue whales. A team of researchers led by Dr Steve Sweetman from the University of Portsmouth identified the two fossilised teeth of the creatures found on the Dorset coast. Portsmouth graduate student Grant Smith made the initial discovery. “Grant was sifting through small samples of earliest Cretaceous rocks collected on the coast of Dorset as part of his undergraduate dissertation project in the hope of finding some interesting remains. Quite unexpectedly he found not one but two quite remarkable teeth of a type never before seen from rocks of this age. I was asked to look at them and give an opinion and even at first glance my jaw dropped,” Dr Sweetman explained in a University of Portsmouth press release. “The teeth are of a type so highly evolved that I realised straight away I was looking at remains of Early Cretaceous mammals that more closely resembled those that lived during the latest Cretaceous – some 60 million years later in geological history. In the world of palaeontology there has been a lot of debate around a specimen found in China, which is approximately 160 million years old. This was originally said to be of the same type as ours but recent studies have ruled this out. That being the case, our 145-million-year-old teeth are undoubtedly the earliest yet known from the line of mammals that lead to our own species.” According to Dr Sweetman, the animals were likely furry, nocturnal creatures. He believes the smaller one may have eaten insects and could have been a burrower, while the larger may have eaten plants as well as insects. “The teeth are of a highly advanced type that can pierce, cut and crush food. They are also very worn which suggests the animals to which they belonged lived to a good age for their species. No mean feat when you’re sharing your habitat with predatory dinosaurs.” The teeth were recovered from exposed rocks in cliffs near Swanage, a site which has yielded thousands of fascinating fossils in the past. According to Smith’s supervisor, Dave Martill, a professor of Biology at the University of Portsmouth, it quickly became apparent that they’d discovered something remarkable. “We looked at them with a microscope but despite over 30 years’ experience these teeth looked very different and we decided we needed to bring in a third pair of eyes and more expertise in the field in the form of our colleague, Dr Sweetman. “Steve made the connection immediately, but what I’m most pleased about is that a student who is a complete beginner was able to make a remarkable scientific discovery in palaeontology and see his discovery and his name published in a scientific paper. The Jurassic Coast is always unveiling fresh secrets and I’d like to think that similar discoveries will continue to be made right on our doorstep.” A study detailing the findings has been published in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. Ancient Egyptian Papyri Ink Contained Copper The black ink used by Ancient Egyptian scribes contained copper, according to new analysis by the University of Copenhagen of 2,000-year-old papyri fragments. It’s generally been assumed that writing ink was primarily carbon-based until the fourth and fifth centuries CE, but by carrying out X-ray microscopy on the fragments, the Danish researchers have shown that copper, an element never before identified in ancient ink, was used. Intriguingly, even though the papyri fragments were written over a period of three centuries and originate from different regions, the team’s results did not show much variation. “The composition of the copper-containing carbon inks showed no significant differences that could be related to time periods or geographical locations, which suggests that the ancient Egyptians used the same technology for ink production throughout Egypt from roughly 200 BCE to 100 CE,” said Egyptologist and first author of the study Thomas Christiansen from the University of Copenhagen. Private papers of an Egyptian soldier named Horus, who was stationed at a military camp in Pathyris, and the Tebtunis temple library, were the two primary sources of the papyri. The fragments all formed parts of larger manuscripts which are currently part of the Carlsberg Collection at the University of Copenhagen. “None of the four inks studied here was completely identical, and there can even be variations within a single papyrus fragment, suggesting that the composition of ink produced at the same location could vary a great deal. This makes it impossible to produce maps of ink signatures that otherwise could have been used to date and place papyri fragments of uncertain provenance,” explains Christiansen. “However, as many papyri have been handed down to us as fragments, the observation that ink used on individual manuscripts can differ from other manuscripts from the same source is good news insofar as it might facilitate the identification of fragments belonging to specific manuscripts or sections thereof.” The researchers suggest that their findings, which have been published in the journal Scientific Reports, could also greatly aid conservation efforts of ancient Papyri. Featured Image: Homo neanderthalensis skull – a hominid fossil reconstruction in the Beijing Museum of Natural History – China, July 2017. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Bjoertvedt ]]>