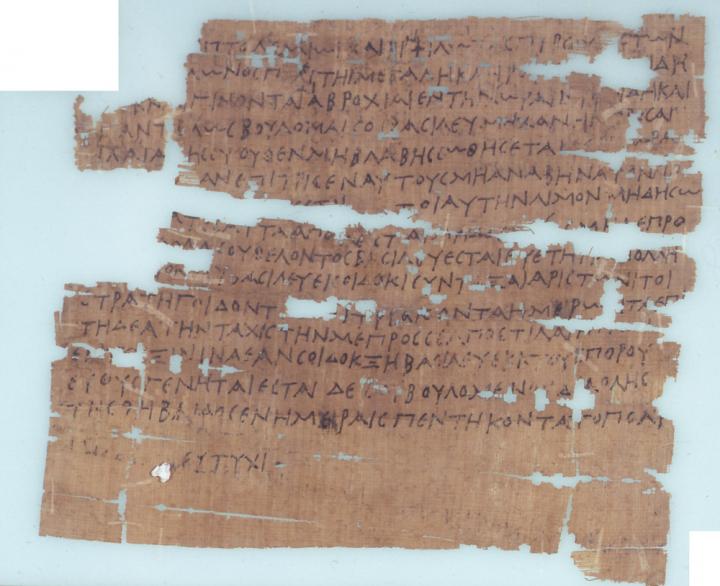

Volcano Led to Unrest in Ancient Egypt An event that “changed everything about Near-East history,” according to Yale University historian Joseph Manning, could be explained by volcanic eruptions. In the middle of a highly successful campaign against the Seleucid Empire, Ptolemy III, leader of the Ancient Egyptian Ptolemaic Kingdom, abruptly decided to return his forces back to Egypt in around 245 BCE. It was a dramatic and hugely significant move which historians have long been unable to explain. Manning and colleagues believe Ptolemy’s actions could be explained by the effects of volcanic eruptions. In particular, they’ve found evidence that by cooling the planet’s atmosphere, major volcanoes can disrupt the flow of the Nile River. This could have led to drastic food shortages in the region, and heightened tensions. Beyond the war with the Seleucid Empire, Manning believes that volcano eruptions could be linked to a host of upheavals and uprisings in Ptolemaic Egypt. Manning’s study, which has been published in the journal Nature Communications, drew on evidence ranging from ice core records to ancient papyri to analyse the effects of climate events on Ancient Egyptian society. “That’s the beauty of these climate records. For the first time, you can actually see a dynamic society in Egypt, not just a static description of a bunch of texts in chronological order,” Manning says. “This is of absolutely enormous importance.” During the Ptolemaic period, which spread from just after the death of Alexander the Great until the death of Cleopatra, Egyptian farmers depended hugely on flooding of the Nile in the summer months to irrigate their grain fields. “When the Nile flood was good, the Nile valley was one of the most agriculturally-productive places in the Ancient World,” says Francis Ludlow, a climate historian at Trinity College in Dublin and a co-author of the new study. “But the river was famously prone to a high level of variation.” If the Nile didn’t flood the land, it could lead to grain shortages. The authors suggest it was one such grain shortage that forced Ptolemy to return home in 245 BCE. The study authors highlight how this lack of flooding in the Nile could have been caused by volcano eruptions elsewhere on the planet. The key is a band of monsoon weather around the equator called the intertropical convergence zone. Most years, in the summer months, this band of weather moves up from the equator and floods one of the major tributaries to the Nile. When volcanoes erupt they blast out sulphurous gases which can ultimately cool the atmosphere. When this happens in the northern hemisphere, it can prevent the monsoon rains moving as far as normal. “When the monsoon rains don’t move far enough north, you don’t have as much rain falling over Ethiopia,” Ludlow said in a press release. “And that’s what feeds the summer flood of the Nile in Egypt that was so critical to agriculture.” Using computer simulations, the team found that poor flood years on the Nile matched up with major volcanic eruptions at locations across the globe. They then found that these volcanic eruptions also preceded major political and economic events that affected Egypt, including Ptolemy III’s abandonment of the campaign against the Seleucid empire, as well as the Theban Revolt. The volcanic eruptions didn’t cause these upheavals on their own, both Ludlow and Manning stress, but they likely added fuel to existing economic, political and ethnic tensions. Ominously, Ludlow claimed the findings could hold a warning for the future. “The twenty-first century has been lacking in explosive eruptions of the kind that can severely affect monsoon patterns. But that could change at any time,” he says. “The potential for this needs to be taken into account in trying to agree on how the valuable waters of the Blue Nile are going to be managed between Ethiopia, Sudan and Egypt.” Permian-Triassic Extinction Happened a Million Years Earlier than Thought New research in the remnants of the Godwanides mountain range has discovered evidence that one of the greatest mass extinction events in history happened earlier than previously thought. “We’ve established that climatic changes related to the devastating end of the Permian mass extinction event about 250 Million years ago were beginning earlier than previously identified,” said Dr. Pia Viglietti from the Witwatersrand University. The Permian-Triassic was one of history’s most significant mass extinction events, wiping out 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. Viglietti analysed fossil rich sediments present in the Karoo region of South Africa, which were deposited in the tectonic events that created the spectacular Gondwanides mountains. She found that the vertebrate animals in the area started to go extinct much earlier than would be expected under conventional dating of the mass extinction event. “The Karoo Basin takes up a huge portion of South Africa and most of us who drive through it do not think much of it,” explained Viglietti. “But if you know what you’re looking for, the Karoo represents a wealth of knowledge about the story of life on Earth.” She continued: “The Gondwanides not only influenced how and where rivers flowed (depositing sediment), it also had a significant effect on the climate, and thus the ancient fauna of the Karoo Basin,” As mountains erode, they place less weight on the earth’s crust, meaning the depression they’ve created in it starts to reduce. 100 million years ago, the Gondwanides would have had this effect on the Karoo region. This process is recorded in the sediment by periods of deposition and non-deposition. “During my PhD, I have identified a new tectonic “loading” event (mountain building event) that kick-started sedimentation in the Latest Permian Karoo Basin,” explained Viglietti. The sediments during this loading event also provided evidence of climatic changes as well as evidence of a previously overlooked “faunal turnover”, which points to the start of the end Permian mass extinction event, according to Viglietti’s findings. “Within the last million years before this major biotic crisis, the animals had already started to react. I interpret this faunal change as resulting from climatic effects relating to the end-Permian mass extinction event – only occurring much earlier than previously identified,” concluded Viglietti. Viglietti’s study has been published in the journal Scientific Reports. Amber Room Discovered? Three German researchers claim to have discovered the most valuable piece of treasure looted by the Nazi regime, the Independent reports. A series of ornate panels, the legendary Amber Room is often considered the most expensive item stolen by the Nazi’s in the Second World War. Embellished with amber and gold leaf, the panels were gifted to Peter the Great in 1716. Estimated to be worth £224 million, their whereabouts has remained a mystery since the end of the war. After examining witness reports compiled by the Stasi and KGB after World War Two, treasure hunters Leonhard Blume, Peter Lohr and Günter Eckhardt concluded that the Amber Room had been hidden in a network of tunnels in a cave in the Ore Mountains, eastern Germany. They used radar to reveal what lay beneath the cave outside the town of Hartenstein, close to the Czech border. “We discovered a very big, deep and long tunnel system and we detected something that we think could be a booby trap,” Blume told The Times. The three explorers also claim to have found evidence of an explosion in the area, which they say fits with witness accounts of items being hidden in the tunnel and then the entrance blown up to hide them. According to the Independent, historians tend to argue that either the Amber Rooms were destroyed in an air raid on Konigsberg, or by Soviet soldiers at the end of the war. Blume, Lohr and Eckhardt are now seeking funding from a sponsor, so they can excavate the location. Featured Image Caption: This piece of papyrus from the mid-Third Century BCE describes a period of famine in Egypt that occurred when the Nile River failed to flood for several years in a row. It was collected from the Egyptian city of Edfu. Credit: © Department of Papyrology, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw ]]>