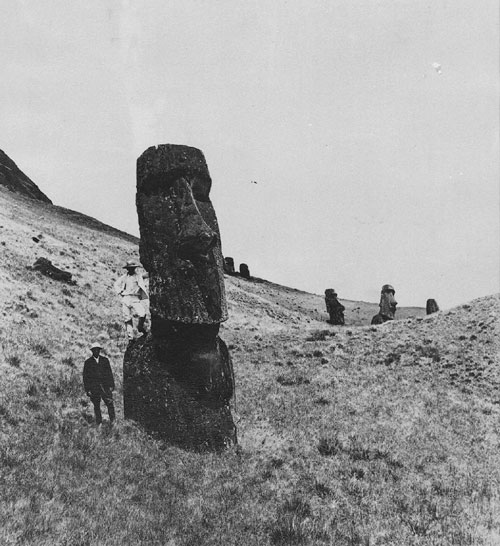

<![CDATA[The biggest history news stories of the last seven days, including a fascinating study into a myth about Saint Francis of Assisi, research that has compared the differences in growth between Homo sapiens and Neanderthal children, and a new study into the people of Rapa Nui prior to the arrival of Europeans. Saint Francis of Assisi Myth Proven true? For more than seven centuries the Friary of Folloni near Montella in Italy has gone to great lengths to protect some small fragments of textile. This is because of a myth claiming the fragments originate from a sack of bread that appeared on the doorstep of the friary in the winter of 1224, a sack allegedly sent from Francis of Assisi and carried to the friary by an angel. Now, an international team of scientists has determined that at least part of this myth is true. C-14 analysis has confirmed that the textile can be dated to between 1220-1295, while there is also evidence that bread had been kept in the sack. “Our studies show that there was probably bread in the sack. We don’t know when, but it seems unlikely that it was after 1732, where the sack fragments were inmured in order to protect them. It is more likely that bread was in contact with the textile in the 300 years before 1732; a period, where the textile was used as altar cloth — or maybe it was indeed on the cold winter’s night in 1224 — it is possible,” said research leader Kaare Lund Rasmussen, a specialist in archaeo-chemical analysis from the University of Southern Denmark, and the leader of the research team. Unfortunately, the researchers have not been able to address the question of how the bread sack ended up at the friary. “This is maybe more a question of belief than science,” said Rasmussen, in a statement. The results of the study have been published in the journal Radiocarbon. New Insights Into How Neanderthals Grew Pioneering research has shed light on how Neanderthals, the closest extinct evolutionary cousins to modern humans, grew. A study led by Antonio Rosas, researcher at the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC), looked at the fossilised remains of an eight-year-old Neanderthal child’s skeleton to establish whether there are any differences in the growth of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens. Published in the journal Science, the study determined that both species do indeed regulate their growth differently. Neanderthals had a greater cranial capacity than modern humans, an intracranial volume of 1,520 cubic centimetres for a Neanderthal adult compared to 1,195 cubic centimetres for a modern human. Tellingly, the intercranial volume of the Neanderthal child had already reached 1,330 cubic centimetres at the time of his death. In other words, it had reached 87.5% of the total by around eight years of age. For a modern human child, the full development of cranial capacity would already have been reached by that age. “Developing a large brain involves significant energy expenditure and, consequently, this hinders the growth of other parts of the body. In sapiens, the development of the brain during childhood has a high energetic cost and, as a result, the development of the rest of the body slows down,” Rosas explained. According to the research, the skeleton and dentition of the young Neanderthal present a physiology which is similar to that of a sapiens of the same age, except for the thorax area, which corresponds to a child between five and six years, in that it is less developed. “The growth of our Neanderthal child was not complete, probably due to energy saving”, explains CSIC researcher Antonio Rosas. It was also determined by the study that the maturation of the Neanderthal child’s vertebral column occurred around two years later than it would in an anatomically modern human. In all hominids, the cartilaginous joints of the middle thoracic vertebrae and the atlas are the last to fuse, but in this Neanderthal, fusion occurred about two years later than in modern humans. “The delay of this fusion in the vertebral column may indicate that Neanderthals had a decoupling of certain aspects in the transition from infancy to the juvenile phase. Although the implications are unknown, this feature could be related to the characteristic enlarged shape of the Neanderthal torso, or slower brain growth”, says Rosas. New Insight into the Size of Rapa Nui’s Population When Europeans first arrived on Rapa Nui (aka Easter Island), they estimated the population to be between 1,500 and 3,000, numbers which seemed strikingly low considering the nine hundred giant stone statues located around the island. Now, a new study hopes to give a new estimation of the population of Rapa Nui, based on the island’s farming potential, and hopefully provide some explanation as to how the spectacular statues could have been built. “Despite its almost complete isolation, the inhabitants of Easter Island created a complicated social structure and these amazing works of art before a dramatic change occurred,” said Dr. Cedric Puleston, lead author of the study, from the Department of Anthropology, University of California, Davis, USA. “We’ve tried to solve one piece of the puzzle – to figure out the maximum population size before it fell. It appears the island could have supported 17,500 people at its peak, which represents the upper end of the range of previous estimates.” He added: “If the population fell from 17,500 to the small number that missionaries counted many years after European contact, it presents a very different picture from the maximum population of 3,000 or less that some have suggested.” Rapa Nui’s history has long been a source of controversy. Much archaeological evidence has suggested that the population had been much higher than the small number encountered by the first Europeans to arrive at the island. What caused this massive population drop-off however, has remained shrouded in mystery, with theories ranging from war to the island’s resources being exhausted through over use. Puleston and colleagues examined the agricultural potential of the island, to calculate how many people the island could have sustained. “We examined detailed maps, took soil samples around the Island, placed weather stations, used population models and estimated sweet potato production. When we had doubts about one of these factors we looked at the range of its potential values to work out different scenarios,” Puleston explained. “The result is a wide range of possible maximum population sizes, but to get the smallest values you have to assume the worst of everything. If we compare our agriculture estimates with other Polynesian Islands, a population of 17,500 people on this size of island is entirely reasonable.” ]]>

History News of the Week – St. Francis of Assisi Myth, Neanderthal Children, and the Rapa Nui