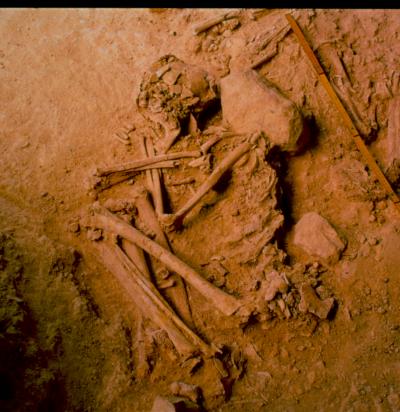

<![CDATA[The biggest history news stories of the week, including two pioneering genome studies that have shed fascinating new light on humanity’s ancient past and its echoes in the present. Present day Lebanese are descendants of Biblical Canaanites A new genome study of ancient remains from the Near East suggests that present day Lebanese people are direct descendants of the Biblical Canaanites. The research, which has been published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, sequenced the entire genomes of 4,000 year-old Canaanites who inhabited the region during the Bronze Age, and compared them to other ancient and present day populations. Despite the Canaanites creating the first alphabet and establishing colonies throughout the Mediterranean, historians and archaeologists only have a limited knowledge of them. They are mentioned several times in the Bible, as well as in ancient Greek and Phoenician texts, but experts know little about their genetic identity, who their ancestors were, and if they have any descendants today. The study by the researchers from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute determined that more than 90% of present Lebanese ancestry is likely to be from the Canaanites, with a small proportion coming from a different Eurasian population. The researchers estimate that new Eurasian people mixed with the Canaanite population about 2,200 to 3,800 years ago at a time when there were many conquests of the region from outside. Details about the Canaanites own ancestry have also been revealed. The study claims that they were a mixture of local people who settled in farming villages during the Neolithic period and eastern migrants who arrived in the area around 5,000 years ago. “For the first time we have genetic evidence for substantial continuity in the region, from the Bronze Age Canaanite population through to the present day.” Dr Claude Doumet-Serhal, co-author of the study and Director of the Sidon excavation site in Lebanon, said. “These results agree with the continuity seen by archaeologists. Collaborations between archaeologists and geneticists greatly enrich both fields of study and can answer questions about ancestry in ways that experts in neither field can answer alone.” Meanwhile, Dr. Chris Tyler-Smith, lead author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, said: “Genetic studies using ancient DNA can expand our understanding of history, and answer questions about the likely origins and descendants of enigmatic populations like the Canaanites, who left few written records themselves. “Now we would like to investigate the earlier and later genetic history of the Near East, and how it relates to the surrounding regions.” Bronze Age Iberia spared the brunt of Steppe invaders New DNA analysis of people who lived in the Iberian Peninsula during the Bronze Age has revealed that they received only minor genetic input from Steppe invaders, suggesting the Steppe migrations played less of a role in the cultural and genetic makeup of Iberian people than they did in populations elsewhere in Europe. Between the Middle Neolithic (4200-3500 BCE) and the Middle Bronze Age (1740-1430 BCE), Central, Northwestern and Northern Europe received a massive influx of people from the Steppe regions of Eastern Europe and Asia. Archaeological digs have gained insights into some of the impacts of these influxes on Iberia, in the form of changing cultural practices and funeral rituals, but the genetic effect has remained hitherto unexamined. The genomes of fourteen people who lived in Portugal in the Neolithic and Bronze Age were sequenced for the study, which has been published in the journal PLOS Genetics. These genomes were then compared with other ancient and modern genetic data, revealing only subtle changes between the Portuguese Neolithic and Bronze Age DNA, suggesting a minor genetic influence from the Steppe. Surprisingly, the changes were significantly more pronounced in paternal lineage. “It was surprising to observe such a striking Y chromosome discontinuity between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, such as would be consistent with a predominantly male-mediated genetic influx” says first author Rui Martiniano. Height was also estimated from the samples, based on relevant DNA sequences, revealing that genetic input from Neolithic migrants decreased the height of Europeans, which subsequently increased steadily through later generations. By showing that migration into the Iberian Peninsula occurred on a much smaller scale than elsewhere in Europe, the study raises questions about the impact this had on language, culture and technology. For example, the fact that the Basque region of Spain speaks a pre-Indo-European language could be explained by these findings. The discovery also supports a theory which says Indo-European languages spread through Europe from the Steppe heartland. The study was carried out by Daniel Bradley and Rui Martiniano of Trinity College Dublin, in Ireland, and Ana Maria Silva of University of Coimbra, Portugal. New project aims to highlight importance of The Indian Army in the First World War In the UK, The Soldiers of Oxfordshire (SOFO) Museum and Oxford University’s History Faculty have received a £12,000 grant from the Arts & Humanities Research Council ‘Voices of War & Peace’ WWI Engagement Centre, for their project titled: The Indian Army in the First World War: An Oxfordshire & Buckinghamshire Perspective. The project aims to shed new light on the British Indian Army’s role in the war on the Eastern Front in Iraq through an outreach programme and touring exhibition. Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus of all ages in the local community are being called upon to engage with researchers by sharing stories, experiences and memorabilia. The touring exhibition will then showcase the findings in November. Photographs that have never been displayed before will explore the experiences of British and Indian soldiers in the conflict, as well as the Iraqi prisoners. Featured image: Archaeological remains of individual MC337 excavated from the site of Hipogeu de Monte Canelas I, Portugal, and analysed by the archaeologist Rui Parreira and the anthropologist Ana Maria Silva. Courtesy of Rui Parreira ]]>

History News of the Week: The Biblical Canaanites' Modern Descendants