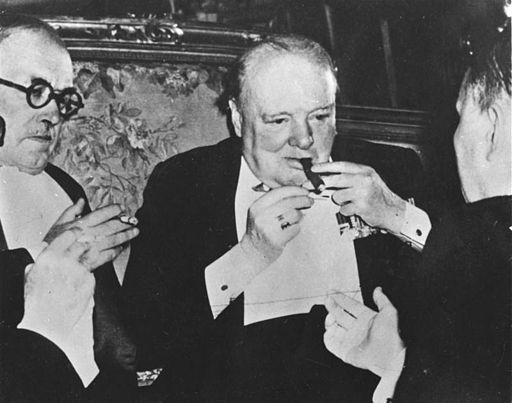

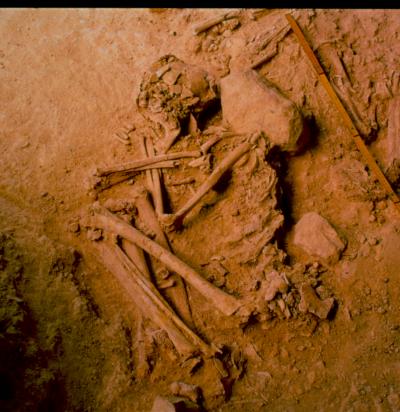

Churchill Tried to Cover-up Nazi Royal Plot Newly released papers from the UK’s National Archives have revealed that Winston Churchill wanted to “destroy all traces” of telegrams about a Nazi plot to reinstate the abdicated King Edward VIII to the throne in return for his support during the Second World War. According to the Guardian, the telegrams reveal a plan to kidnap the Duke of Windsor – as the abdicated monarch was then known, and his wife Wallis Simpson, in Portugal in 1940. The Cabinet Office papers released by the National Archives reveal a 1953 appeal from Churchill to US president Dwight D Eisenhower and the French government to prevent publication of the telegrams for at least “10 to 20 years”, the Guardian reports. Churchill believed the telegrams were likely to give the misleading impression that the duke was in regular touch with German agents, and open to ideas which were disloyal. The prime minister’s appeal was made after he’d learnt a microfilm of the documents had fallen into the hands of the US State Department, and were being considered for inclusion in the US’ official history of the war. Although Churchill succeeded, and publication of the telegrams was delayed by a few years, they still eventually came to light in 1957. “Ghost” Species Points to Interbreeding Between Humans and Other Hominins Through studying saliva, scientists have discovered clues to a “ghost” species of archaic humans that may have contributed genetic material to the ancestors of people living in Sub-Saharan Africa today. The new findings add to growing evidence that sexual relationships between different species of archaic humans might not have been unusual, and in fact the norm. Previous research has already concluded that the ancestors of modern humans interbred with other hominin species, such as Neanderthals and Denisovans, in Asia and Europe. The latest research, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, adds to other recent genetic analyses indicating ancient Africans also interbred with other early hominins. “It seems that interbreeding between different early hominin species is not the exception — it’s the norm,” said Omer Gokcumen, PhD, an assistant professor of biological sciences in the University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences. “Our research traced the evolution of an important mucin protein called MUC7 that is found in saliva,” he said. “When we looked at the history of the gene that codes for the protein, we see the signature of archaic admixture in modern day Sub-Saharan African populations.” The MUC7 protein gives spit its slimy consistency, as well as binding to microbes, which may help the body get rid of disease-causing bacteria. The team of scientists were researching the purpose and origins of the protein by examining the gene in more than 2,500 human genomes, when they discovered that one group from Sub-Saharan Africa had a significantly different version to that found in other humans. “Based on our analysis, the most plausible explanation for this extreme variation is archaic introgression – the introduction of genetic material from a ‘ghost’ species of ancient hominins,” Gokcumen says. “This unknown human relative could be a species that has been discovered, such as a subspecies of Homo erectus, or an undiscovered hominin. We call it a ‘ghost’ species because we don’t have the fossils.” The study was led by Gokcumen and Stefan Ruhl, DDS, PhD, a professor of oral biology in UB’s School of Dental Medicine. Humans May Have Arrived in Australia 10,000 Years Earlier than Thought Newly discovered artefacts suggest humans arrived in Australia 10,000 years earlier than previously believed. Exactly when Australia was first settled by humans has long been shrouded in ambiguity, with recent studies seemingly pushing the approximate date further and further back in time. A team of researchers led by the University of Queensland, and including scientists from the University of Washington, found and dated artefacts from Madjedbebe, Northern Australia that suggest humans arrived there 65,000 years ago. A paper detailing the artefacts and the dating method has been published in the journal Nature. The new findings could have a significant impact on theories about the emergence of early humans and how they coexisted with their environment. In particular, according to the researchers it throws serious doubt on the idea that humans caused the extinction of megafauna such as giant kangaroos, wombats and tortoises. “Previously it was thought that humans arrived and hunted them out or disturbed their habits, leading to extinction, but these dates confirm that people arrived so far before that they wouldn’t be the central cause of the death of megafauna,” co-author and UW associate professor of anthropology Ben Marwick said. “It shifts the idea of humans charging into the landscape and killing off the megafauna. It moves toward a vision of humans moving in and coexisting, which is quite a different view of human evolution.” Among the artefacts discovered were ochre crayons and other pigments, as well as objects believed to be the world’s oldest edge-ground hatchets, potential evidence that these ancient humans ground seeds and processed plants. The artefacts were dated using radiocarbon dating and optical stimulated luminescence (OSL) – a technique used on minerals that can reveal a variety of things, such as the last time a grain of sand was exposed to sunlight – useful for determining when an artefact was buried. Featured Image courtesy Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-14059-0005 / CC-BY-SA 3.0 [CC BY-SA 3.0 de (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/de/deed.en)], via Wikimedia Commons ]]>