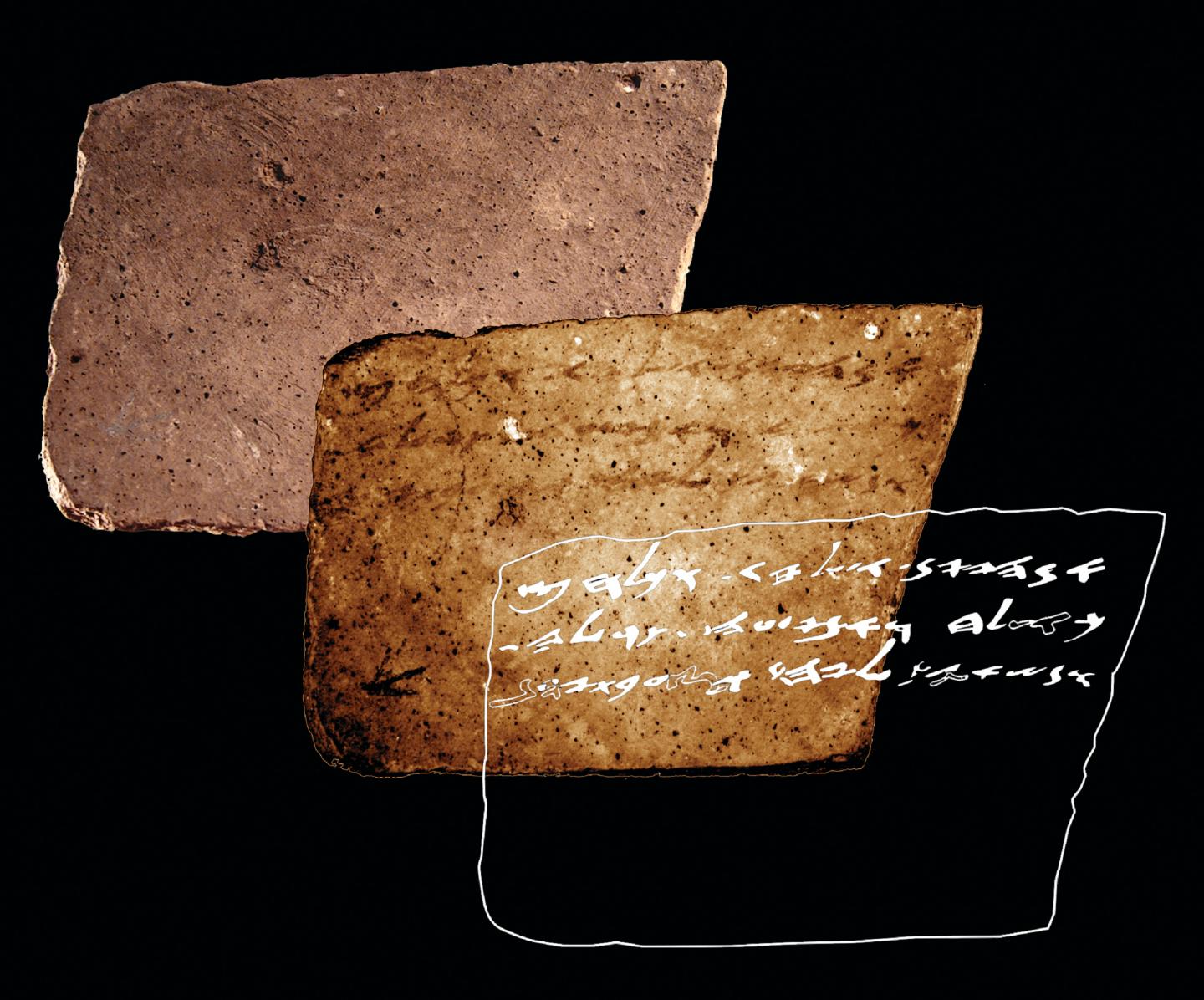

<![CDATA[The biggest history news stories of the last seven days, including a study that suggests the Nazi regime was far more tolerant of lesbians than one might expect. Limited toleration of Lesbianism in Nazi Germany A new study claims that the Nazi regime, infamous for its discrimination and oppression, had some toleration for Lesbians. Samuel Clowes Huneke, a doctoral candidate in history at Standford University in the USA, analysed police examination files from the 1940s related to alleged violations of same sex relations laws. His findings have been published in the Journal of Contemporary History. “These files add a new level of nuance to existing scholarship,” Huneke said in a statement from Stanford. “They hint at a more normal existence that was the daily experience of some lesbians in the Third Reich.” The Nazi regime’s persecution of homosexual men is well known, with homosexual acts between men explicitly criminalised. Somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000 alleged homosexual men were incarcerated in concentration camps under the Nazi regime, with up to 60% of them dying in the camps. The experience of homosexual women in Nazi Germany however, is much more ambiguous, especially because women were excluded from the laws that made homosexuality illegal among men. Huneke argues that Nazi officials didn’t view lesbians as a threat, as women were banned from most spheres of politics and public life “In light of both the fearsome persecution of homosexual men and scholarship that places it in the context of National Socialist pronatalism, the regime’s seeming lack of interest in female homosexuality is startling, for in other respects the government placed considerable burdens on women,” writes Huneke, who is working on a dissertation about the history of homosexuality in postwar Germany. Files Huneke discovered in 2015 show that Nazi authorities investigated eight women in Berlin, all denounced for violating same sex laws. In each case, authorities determined the women could not be prosecuted for same-sex relations under the criminal code. “To scholars accustomed to seeing in the Nazi state a jungle of overlapping jurisdictions, personal initiative and law based solely on the Führer’s wish, this is a curious portrait of the Nazi justice system, one marked by an unexpected concern for the strict interpretation of statute,” Huneke writes in his article. Invisible Hebrew inscription revealed Tel Aviv University (TAU) researchers have discovered and deciphered an invisible inscription on the back of a pottery shard which has been on display in the Israel Museum for over 50 years. The ostracon – an ink inscribed pottery shard, dates back around 2,600 years, to the period just before the destruction of the kingdom of Judah by Nebuchadnezzar. An inscription on the ostracon’s front side was noticed when the object was first unearthed in 1965, and has been thoroughly studied by scholars. Opening with a blessing by Yahweh, it also discusses money transfers. The back of the shard had been considered blank however, until now. “Using multispectral imaging to acquire a set of images, Michael Cordonsky of TAU’s School of Physics noticed several marks on the ostracon’s reverse side. To our surprise, three new lines of text were revealed,” said Arie Shaus of TAU’s Department of Mathematics and one of the principal investigators of the study published in the journal PLOS ONE. Deciphering 17 words on the object’s reverse, the researchers concluded it was a continuation of the text on the front side. “The new inscription begins with a request for wine, as well as a guarantee for assistance if the addressee has any requests of his own,” said Shaus, in a statement. “It concludes with a request for the provision of a certain commodity to an unnamed person, and a note regarding a ‘bath,’ an ancient measurement of wine carried by a man named Ge’alyahu.” Tel Arad was a military outpost at the southern border of the kingdom of Judah, stationing 20 to 30 soldiers. One tonne World War Two bomb exploded at Sevastopol Explosive experts in Sevastopol have successfully destroyed a one-tonne World War Two bomb, according to the Daily Mail. The parachute mine was found seventeen metres under the surface, in the bay of Sevastopol, on the Crimean Peninsula. It seems likely that the massive bomb was dropped in 1941 as part of a Nazi campaign to block the entrance to Sevastopol’s port – in turn disrupting shipping to and from the city. According to the Daily Mail, the bomb had to be destroyed due to its proximity to a gas pipeline, hydraulic engineering facility and a shellfish farm. The delicate operation took nine hours, and saw divers move the bomb into open sea, before it was detonated remotely using a robot submarine. The ferocious detonation included a massive amount of seawater being blown some 100 feet (30.5 metres) into the air. ]]>

History News of the Week: Did the Nazis Tolerate Lesbians?