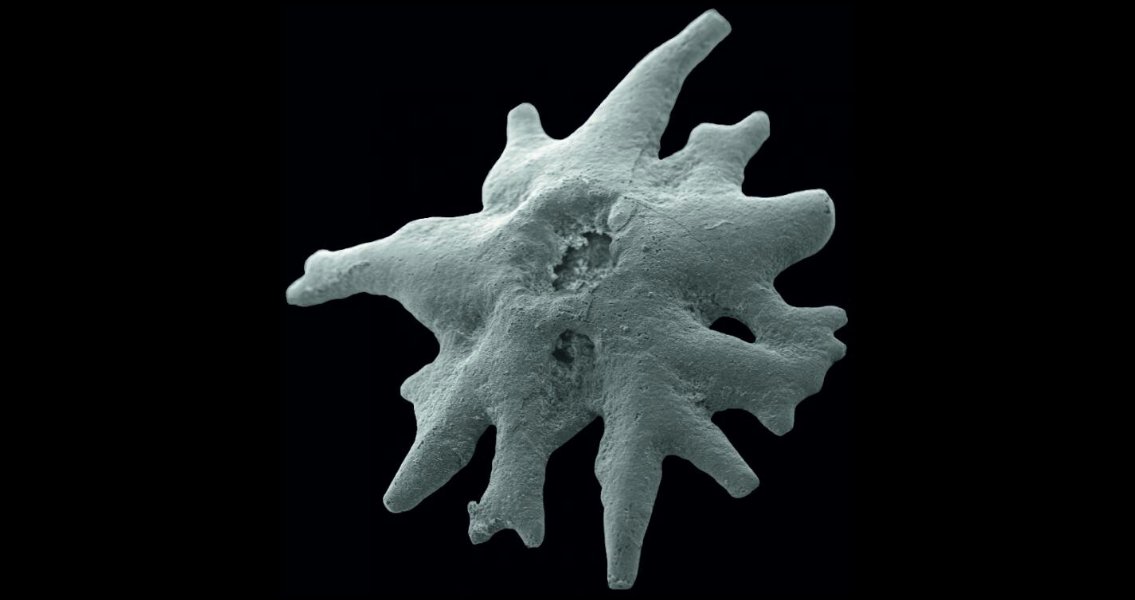

<![CDATA[A 425-million-year-old fossil of a juvenile crinoid, a distant ancestor of the sea lily, has been found in a unique place – the remains of a trench dug on the border between Italy and Austria during the First World War. According to a press release from Ohio State University (OSU), the rare find was found encased in iron oxide and limestone in the Cardiola Formation, a region of the Austrian Alps that was exposed by trenches dug during the Great War. The characteristics of the fossil have been able to provide researchers new ideas on how some of the earliest animals to inhabit the planet came to proliferate in the Earth’s seas. The crinoid, which used to carpet the ocean floor in great numbers, was at one time an abundant animal. The creatures, which resembled spindly and plant-like animals that would anchor themselves to the ocean floor, are mostly known from the fossilized remains of fully-grown crinoids. Finding the fossilized remains of juvenile crinoids is quite rare in comparison. OSU earth science professor William Ausich, co-author of a recent study of the juvenile fossil, said the new find is even more exciting because of one very important feature: the juvenile crinoids found in the Cardiola Formation had not been attached to rocks when they died. Instead, whatever they had been attached to didn’t fossilize along with the crinoids. This leads Ausich to believe that these juvenile crinoids were likely attached to objects that had been free-floating in the water. Another theory, the earth science professor said, was that they had been attached to a second bottom-dwelling creature that lacked the hard parts that would have been preserved by the fossilization process. What kind of creatures could these crinoids have clung to on their trek through the waters? Scientists say that a free-floating algae bed or a swimming cephalopod could have been the culprits. Either of these answers would have resulted in the crinoids being carried far from the spot where they began their lives as larvae. Modern sea lilies, the closest living relative to the crinoid, begin as larvae as well. These larvae grow until the free-floating juvenile sea lily attaches itself to the seafloor. After around 18 months, these juveniles reach adulthood. Yet the new evidence raises the suggestion that ancient crinoids might have spread far and wide as juveniles by settling on objects that were much more mobile. It could provide clues to the wide geographic distribution of the sea creature, Ausich said, especially since these nomad juveniles could have traveled leagues before reaching reproductive age. The modern sea lily and the ancient crinoid have several similarities, including long, stem-like bodies that resemble flowers thanks to the feathery fronds at their highest point. The center of the crinoid “flower” would have been a mouth, while its so-called petals would have been used for capturing plankton for food. Like the sea lily, the crinoid had a star-shaped organ on its lower end to hold tight to the sea floor. In modern sea lilies this organ, called a “holdfast”, does have the ability to let go and navigate the sea lily over short distances. However, it’s a rare occurrence, and if crinoids lived their lives along similar lines, there needs to be some explanation as to how they spread across the ancient globe. The recent research paper, published in the journal Geologica Acta, can be found online here Image courtesy of Ohio State University]]>

Rare Fossil Discovered in remnants of Trench From WWI