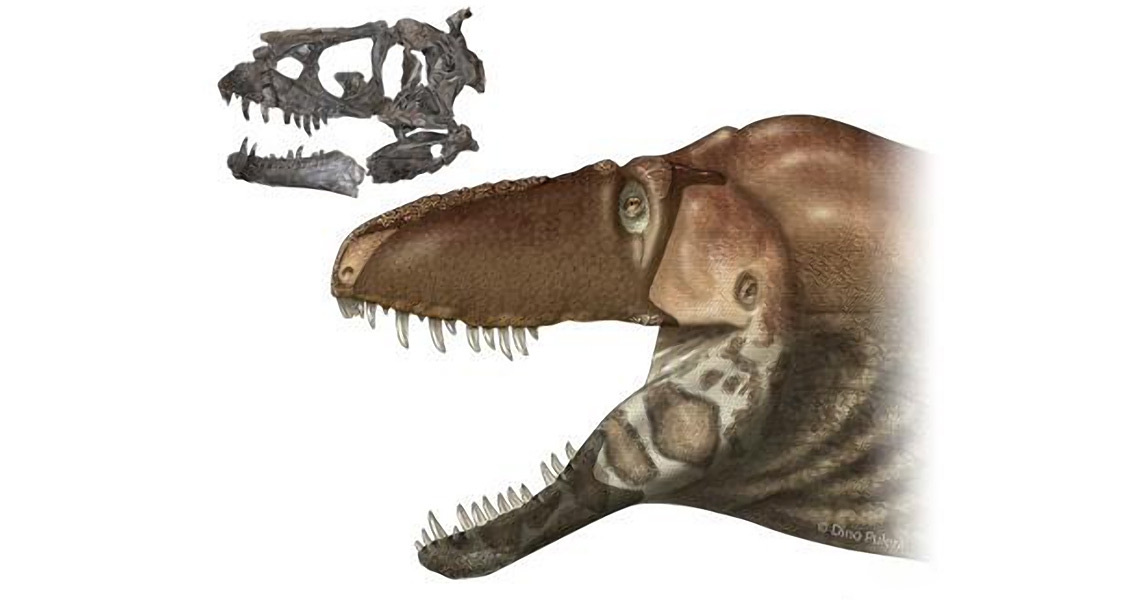

Daspletosaurus horneri – “Horner’s Frightul Lizard” – the new species is named after renowned paleontologist John “Jack” R. Horner. Horner, a former curator at the museum of the Rockies, discovered numerous dinosaur fossils in the region and also mentored local students towards scientific careers. “Being a tyrannosaur, they had really small arms,” said UNM Honors College Professor Jason R. Moore, who was involved in the discovery. “They wouldn’t be able to interact with their environment with their hands the way mammals do — find food, build nests, tend to eggs and young. In order to do these things, Daspletosaurus needed to use its feet or head. The discovery and analysis of the tyrannosaur shows that the dinosaur had a developed face sensitivity similar to the sensitivity in our finger tips, suggesting it could use its snout for all those complex ecological interactions, similar to the way crocodiles do today.” Published in Nature Publishing Group’s Scientific Reports, the study led by Thomas Carr of Carthage College’s Department of Biology in Wisconsin sheds new light on the development of the tyrannosaur lineage. “Daspletosaurus horneri was the youngest, and last, of its lineage that lived after its closest relative, D. torosus, which is found in Alberta, Canada,” explained Carr. “The geographic proximity of these species and their sequential occurrence suggests that they represent a single lineage where D. torosus has evolved into D. horneri.” The team’s research suggests the evolution of the tyrannosaurs was slow, the transition from D. torosus to D. horneri taking two million years. Carr and colleagues’ study stands to drastically enhance our understanding of tyrannosaurs, revealing a great deal about how their faces would have looked. “It turns out that tyrannosaurs are identical to crocodylians in that the bones of their snouts and jaws are rough, except for a narrow band of smooth bone along the tooth row,” explained Carr. “We did not find any evidence for lips in tyrannosaurs: the rough texture covered by scales extends nearly to the tooth row, providing no space for lips.” “However, we did find evidence for other types of skin on the face, including areas of extremely coarse bone that supported armor-like skin on the snout and on the sides of the lower jaws. The armor-like skin would have protected tyrannosaurs from abrasions, perhaps sustained when hunting and feeding.” Like crocodylians, tyrannosaurs had highly sensitive snouts and jaws, penetrated by numerous small nerve openings which would have allowed a multitude of branches of nerves to innervate the skin. This reveals a great deal about the development of the trigeminal nerve, responsible for sensations and motor actions in the face. “The trigeminal nerve has an extraordinary evolutionary history of developing into wildly different ‘sixth senses’ in different vertebrates, such as sensing magnetic fields for bird migration, electroreception for predation in the platypus bill or the whisker pits of dolphins, sensing infrared in pit vipers to identify prey, guiding movements in mammals through the use of whiskers, sensing vibrations through the water by alligators and turning the elephant trunk into a sensitive ‘hand’ similar to what has been done to the entire face of tyrannosaurs.” explained Jayc Sedlmayr, professor at the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center New Orleans. Image courtesy of @Dino ]]>