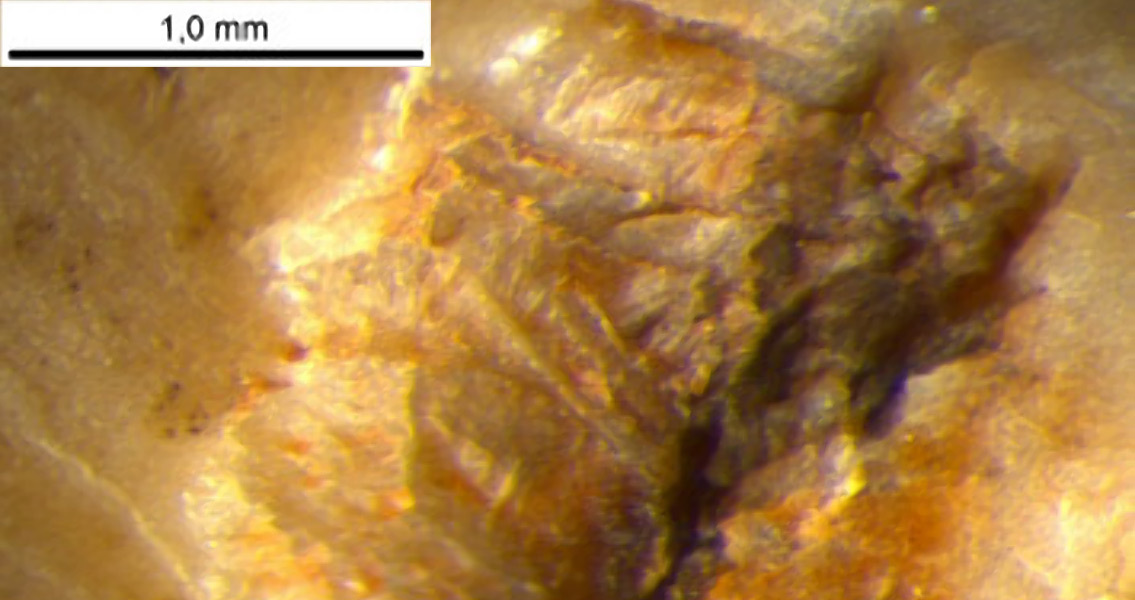

Ars Technica, the remains in question show no signs of violence, indicating that the bodies were likely consumed after death. Identifying cannibalism can be a tricky business, but Morales-Pérez and his team say the evidence was clear. The bones themselves were discovered buried alongside the remains of other, non-human animals; bore signs of being burned and butchered, and evidence of being bitten and scraped. Radiocarbon dating has set the age of the bones to between 9,000 and 10,000 years old. Finding evidence of the practice of cannibalism during this time period is not unheard of, though this is the first time that cannibalism has reared its ugly head in Spain during the Mesolithic. Other archaeological finds throughout Europe and the Levant dating to this time period have yielded evidence of humans eating their own. Additional questions have arisen after discovering the cannibalism. One such question – one that may not ever be able to be answered – is why the humans inhabiting this cave in Spain decided to turn to the practice in the first place. Necessity due to starvation is always one reason for cannibalism, but the multitude of animal remains found in the cave indicates that the food sources for the humans living there were varied and apparently abundant. Occasional periods of privation do occur of course, and the evidence of cannibalism could represent a desperate time in the lives of the people who lived there when food sources were scarce. However, the possibility that the cannibalism might have been ritual in nature cannot be discounted – there’s precedent of complex rituals for eating the flesh of the deceased, often important members of the community, dating back thousands of years. The beginning of the Mesolithic also represented a time period when humans were beginning to transition from their hunter-gatherer existence of the earlier Paleolithic, and taking up the trappings of a more sedentary, agrarian lifestyle. The conflict between these two ways of life could have precipitated some funerary practices that would seem gruesome and barbaric to our own modern sensibilities, researchers say. The state of the remains seems to contradict the idea that they were consumed as part of a ritual. Seemingly dumped unceremoniously in a midden heap at the rear of the cave, these butchered, fire-processed and chewed human bones don’t seem to have been treated with much care. However, with literally ten thousand years having passed between the event and the discovery of the evidence of that event, there’s no way of knowing if the remains had at one time been buried with reverence and then ended up in a new location due to rain runoff and soil erosion. The new research study, published in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, can be found online here Image courtesy of Journal of Anthropological Archaeology]]>