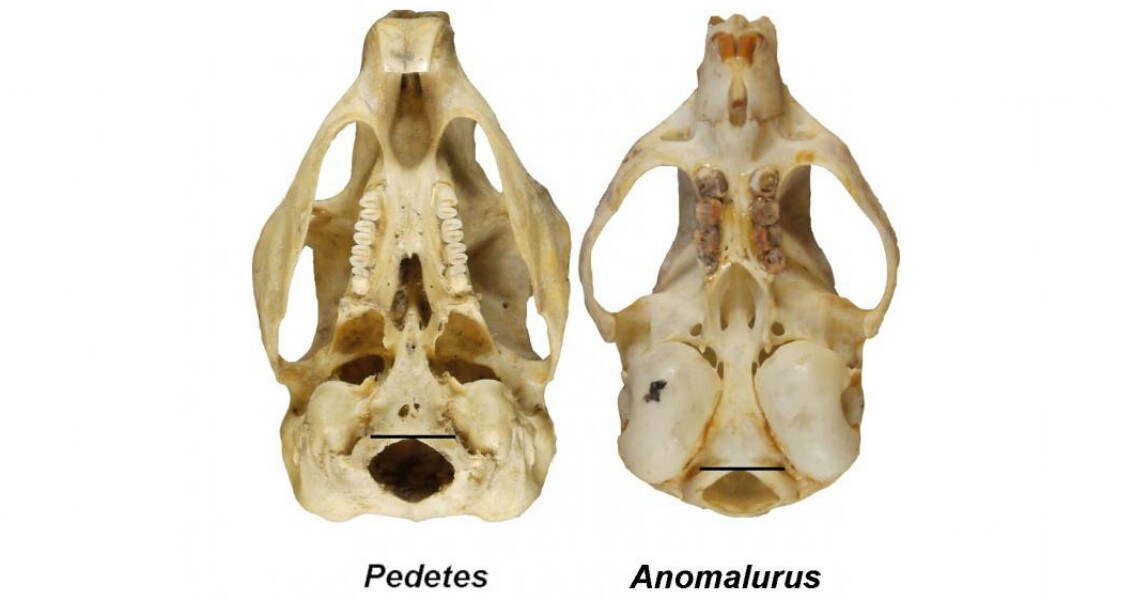

<![CDATA[The modern human skull and walking on two legs evolved together, according to a newly published study from the University of Texas at Austin and Stony Brook University. The findings have the potential to solve one of the most fascinating mysteries of human evolution. A key feature of the human skull can be used to detect the development of bipedalism (walking on two legs) in humans, according to the study published in the latest edition of the Journal of Human Evolution. This connection has long been highly controversial among biologists and archaeologists. The earliest humans climbed trees and walked on the ground, offering them flexibility of movement and the ability to evade predators. It is widely held that between 6 and 3 million years ago the gradual transition began from climbing trees to walking upright the majority of the time. This switch to exclusively walking on two legs inevitably coincided with significant physical changes, such as longer legs. Homo erectus, around 1.9 millions years ago, had leg and thigh bones very close to those of modern humans, evolved for walking on two legs over long distances. Humans differ from other primates in that the foramen magnum, the large hole at the base of the skull which the spinal cord passes through, is shifted forward. Many scientists argue that this is down to the evolution of bipedalism – the head needing to be balanced directly on top of the spine to aid walking. This connection between the foramen magnum and bipedalism is far from universally accepted, however. In 1925, Raymond Dart first questioned the connection in his description of ‘Taung child’, a 2.8 million-year-old fossil skull of the extinct South African species Australopithecus africanus. Last year, a study by Kent State University biological anthropologist Aidan Ruth further questioned the connection between walking on two legs and the forward shifted foramen magnum. Gabrielle Russo, an assistant professor at Stony Brook University, and UT Austin anthropologist Chris Kirk have provided convincing evidence in their new study that the forward shifted foramen magnum is not just a feature of humans and their fossil relatives, but bipedal mammals more generally. “This question of how bipedalism influences skull anatomy keeps coming up partly because it’s difficult to test the various hypotheses if you only focus on primates,” Kirk said in a press release. “However, when you look at the full range of diversity across mammals, the evidence is compelling that bipedalism and a forward-shifted foramen magnum go hand-in-hand.” Their groundbreaking study sampled the largest number of mammal species to date, as well as deploying new methods to measure aspects of foramen magnum anatomy. By comparing the position and location of the foramen magnum in 77 mammal species, from primates to rodents, Russo and Kirk make their case that bipedal mammals have a more forward-positioned foramen magnum than even their most closely related quadrupedal relatives. “We’ve now shown that the foramen magnum is forward-shifted across multiple bipedal mammalian clades using multiple metrics from the skull, which I think is convincing evidence that we’re capturing a real phenomenon,” Russo said. Establishing the link between bipedalism and the foramen magnum’s position is hugely significant. The connection could allow archaeologists to determine much more accurately whether extinct fossil hominids walked on two feet like modern humans, or on four like modern great apes. The specific measurements offered by the study could be applied to future research to provide a map of the evolution of bipedalism. “Other researchers should feel confident in making use of our data to interpret the human fossil record,” Russo concluded. Image shows comparison of the positioning of the foramen magnum in a bipedal springhare (left) and its closest quadrupedal relative, the scaly-tailed squirrel (right). Image credit: Russo and Kirk, Journal of Human Evolution ]]>

Walking On Two Legs Changed Evolution of Human Skulls