<![CDATA[A new study reports that the DNA some humans inherited from our ancient ancestors the Neanderthals is still influencing physical traits such as height, diseases developed and how the immune system functions in some modern humans. Neanderthal DNA was inherited by early humans of non-African descent whose ancestors mated with Neanderthals around 50,000 years ago, and this genetic legacy still has control of some people’s genes. According to the study, the influence of Neanderthal DNA diminished more quickly in the parts of the body which evolved faster during this time period, particularly the brain. This suggests that when our human ancestors acquired the ability for problem-solving and sophisticated language, mating with Neanderthals rapidly declined. However, Neanderthal control of some human genes continues, with both positive and negative results. The study is the result of the analysis of the DNA taken from 214 people in the United States, with a focus on people of European descent. The team of experts at the University of Washington in Seattle compared the modern DNA with DNA from Neanderthals and was able to determine that fragments of Neanderthal genes had survived and remained active in 52 separate types of human tissue. Researchers discovered some people had one Neanderthal copy and one human copy of the same gene. After comparing these copied genes, researchers found that 25 percent exhibited differences in the activity between the Neanderthal and the human copies of the same gene. More significantly, the experts were able to determine which variant was dominant. For example, Neanderthal DNA may still be causing some people to grow taller while shielding them from developing schizophrenia. The gene ADAMTSL3 is known to be a risk factor for developing schizophrenia, however, the Neanderthal DNA reduces the risk of the disease while the person’s height is increased. “Strikingly, we find that Neanderthal sequences present in living individuals are not silent remnants of hybridisation that occurred over 50,000 years ago, but have ongoing, widespread and measurable impacts on gene activity,” Joshua Akey from the University of Washington, who led the research team, explained in an article in New Scientist. “The results add to increasing evidence that these effects are often the outcome of changes to the genetic switches,” said Tony Capra of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. His own results published last year revealed Neanderthal influences on a variety of human disorders, including depression and addiction. The control of Neanderthal DNA decreased the most in regions of the brain critical for perception and fine motor skills, the basal ganglia and the cerebellum, which further evolved in humans to enable advanced thinking, behavior and the ability to process language. NTRK2 is another Neanderthal gene with fading influence. This gene is key to neuron survival in addition to the development of brain connections and its reduced influence illustrates the sort of fine-tuning which may have permitted our ancestors to take off intellectually. Another gene in which Neanderthal DNA lost control is a testes gene that affects a sperm’s ability to penetrate and subsequently fertilize an egg. Researchers theorize that once control of this gene was relinquished, neither the Neanderthals nor the human- Neanderthal hybrids were able to mate with humans. This theory is consistent with research results showing a reduction in the health of male offspring from hybrid unions. ]]>

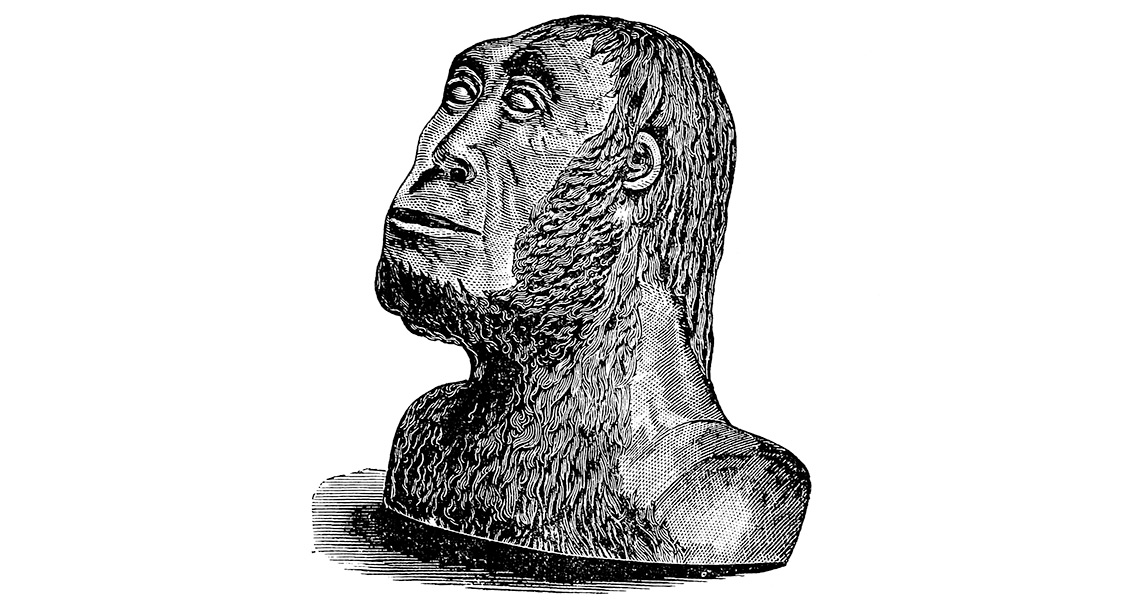

Neanderthal DNA Still Affecting Modern Humans