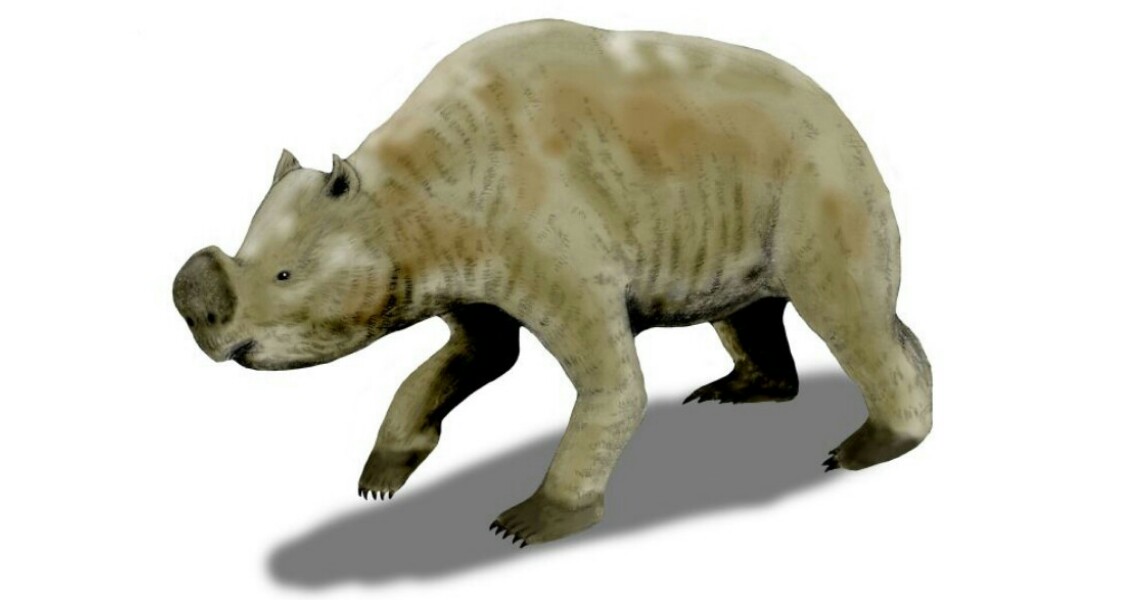

<![CDATA[Australia was once the home of megafauna that included giant birds, reptiles and marsupials. The cause of their extinction, however, has been debated for more than a hundred years, despite scientific advances. Nineteenth century scientists such as British anatomist Sir Richard Owen and Prussian scientist Ludwig Leichhardt asked the same question heard today: were people behind the megafauna's demise or was climate change the culprit? In zoological terms megafauna are defined as large or even giant animals. Although the weight threshold an animal is required to meet varies from over 40 kilograms (90 lbs.), over 44 kilograms (100 lbs.), or over 1,000 kilograms (2,205 lbs.), the most commonly used criteria is a land mammal that’s larger than a human and not domesticated. New research suggests that Australia’s early humans lived at the same time as the megafauna, perhaps for thousands of years prior to their extinction. In the past, it had been theorized that a fire may have dramatically altered early Australia’s landscape and ecology, with one species of bird in particular: Genyornis newtoni, which was giant and flightless, believed to have succumbed to predation due to major changes in its habitat. This theory is now being been questioned due to new evidence. Additionally, the study of fire sensitive plants shows no sign of the genetic bottlenecks a significant fire event would have caused. Furthermore, genomic research indicates that significant population changes didn’t occur until around 10,000 years ago, suggesting aboriginal populations remained small for tens of thousands of years. One specimen, Zygomaturus trilobus, discovered several decades ago may have finally provided the answer. Large and lumbering with big flared cheek bones (zygomatics), Zygomaturus was a marsupial generally the size of a large bull. Little is known about its ecology, or why it went extinct. Excavated on two different occasions during the 1980s, the animal’s upper jaw was shipped to the Australian Museum in Sydney where it was stored still surrounded by the original sediments. The lower part of the jaw is on display at Mungo National Park. Optically stimulated luminescence dating (OSL) was used to test the sediment samples, while the fossils were tested directly using uranium series (U-series) dating. The tests show the specimen died approximately 33,000 years ago. Aborigines arrived in the region about 50,000 years ago. The Zygomaturus specimen indicates megafauna and people coexisted for 17,000 years at least. In fact, the species appears to have lived until the dramatic climate change referred to as the last glacial cycle prior to the Last Glacial Maximum. This date of 33,000 years does not necessarily represent the extinction of Zygomaturus. The deteriorating climatic conditions could have made Willandra Lakes a refuge for both people and megafauna as the surrounding plains became drier, bringing species like the Zygomaturus into increased contact with people. Regardless, the fossil has caused a shift in the debate over megafauna extinction. The research has been published in the Quaternary Science Reviews journal. ]]>

New Research Reveals Australian Megafauna Coexisted with People