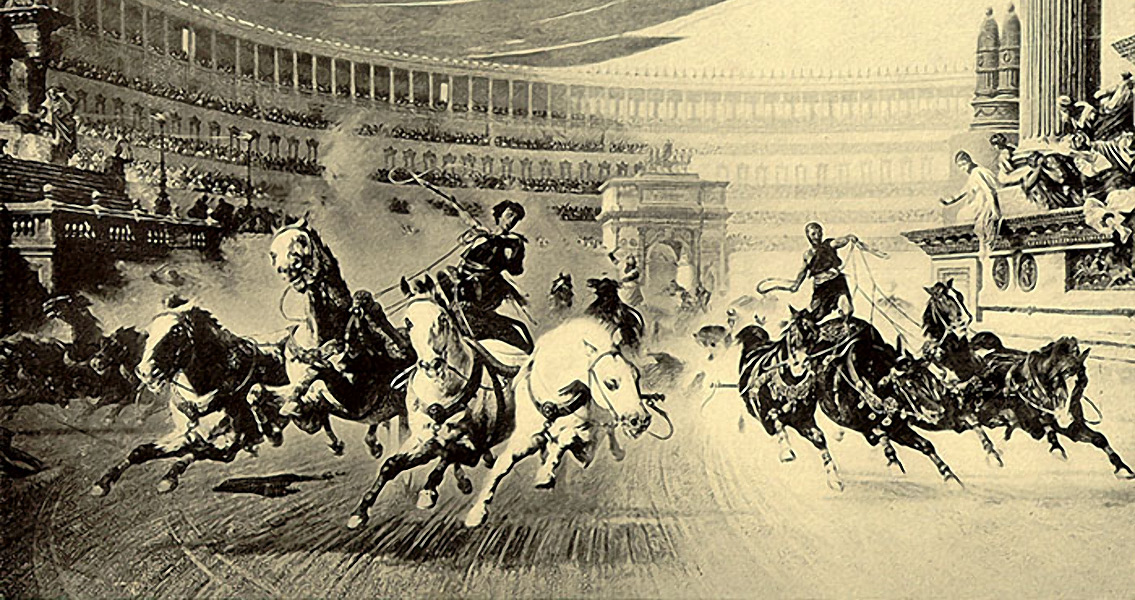

Seeker. “Any iron tire for racing would be a very thin strip of iron on the outside of the wooden rim, best when heat-shrunk on the wood, to consolidate the whole wheel. The solution makes full sense in engineering thinking, ancient or modern.” Horse and chariot races were part of the sacred games, known as ludi, which were held during archaic Roman festivals. The race’s sacral meaning, although diminished across time, has been preserved by the iconography found at Rome’s primary racetrack, the Circus Maximus. No actual Roman chariots are known to have survived. The small toy model, currently being displayed at the British Museum, is the only archaeological evidence for the reinforced single-tire design. The bronze, hand-sized model represents a biga, a racing chariot with two wheels, driven by two horses. The model is missing the charioteer as well as one of the horses and was likely a toy for a prosperous individual, possibly even Emperor Nero himself who, according to historians, played with toy chariots. “The wheels originally rotated freely on the axle. It was made by someone who knew a lot about racing chariots,” Sandor says in the article. Given that it’s easier to guide horses into left-turns, a majority of chariot races ran counter-clockwise. Therefore, chariots’ had only the right wheels strengthened because the chariots naturally leaned right, overloading the right wheel during left-hand turns. The single tire reinforcement configuration didn’t always mean a faster chariot, however, it may have prevented the wheel from failing, consequently reducing crashes. This alone made it statistically superior on the racetrack. In general, Sandor estimates that the chariots with no iron tires had a 50 percent chance of winning, while vehicles with two iron tires would only win 30 percent of the time. The study, which has been published in the Journal of Roman Archaeology, found that a racing chariot with one iron tire on the right was the best design in regards to durability, safety and chance of winning. ]]>