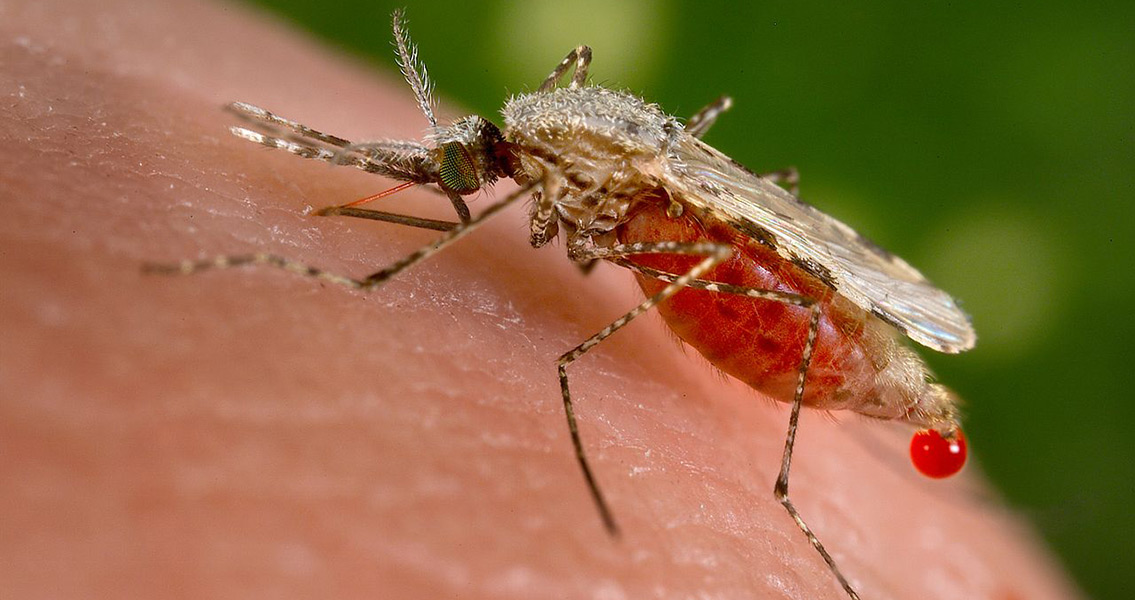

<![CDATA[The denizens of the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago suffered from malaria, the modern malady that plagues the current world – and it was the exact same strain of the disease that’s present today. In a new breakthrough study, scientists have found DNA evidence enabling them to positively identify the type of malaria that plagued individuals interred in three different cemeteries in Italy dating from the imperial period. Taking genetic samples from the teeth of 10 children and nearly 60 adults, the researchers found that the specific strain of malaria that had infected these individuals was the same as the most common one today: Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria, which can cause a flu-like illness, chills and fever in those it infects, was likely a significant force in ancient Rome resulting in widespread death, according to Hendrik Poinar, the director of McMaster University’s Ancient DNA Center in Canada. The evolutionary geneticist and one of the authors of the new research report said in an interview with CNN that the death toll from Malaria in ancient Rome could have been close to the toll it takes in modern Africa. There are approximately 438,000 fatalities a year from malaria, according to the World Health Organization, and the vast majority of these cases – a full 91 percent – originate from sub-Saharan Africa, despite the treatable and preventable nature of the disease. Prior to this new discovery, the only evidence of malaria – or illnesses with symptoms that matched malaria – was found in texts from the period. Poinar stated that there were difficulties classifying these illnesses as malaria. There were simply too many infections that cause fevers for a malaria diagnosis to be definitive. However, the clues were there, especially since the outbreaks seemed to be repeated at the same time each year. This indicated that the culprit could be malaria, as it’s possible to be re-exposed again and again without building immunity to the infection. However, without any sort of DNA evidence to back up the theory, there was no way to support it with raw data – until now. Malaria was found to be quite widespread, not only present on the coast of the Italian peninsula but also in deep inland rural regions as well. Normally it would be next to impossible to find evidence of malaria infection in 2,000-year-old remains as the parasites most often leave evidence behind in organs that decompose quickly, and do not cause changes in skeletal remains. New methods allow scientists to extract minute particles of DNA from dental pulp, purifying and enriching the remains enough to test for the presence of modern malaria. The researchers used an innovative method that has been employed in studying the plague and cholera which involves attaching molecules of a modern version of the pathogen with magnetic beads. These beads “pulled down” the low concentration of parasite DNA and found its signature. The new research study, which appears in the journal Current Biology, can be found here]]>

Modern Malaria Parasite Found in Ancient Roman DNA