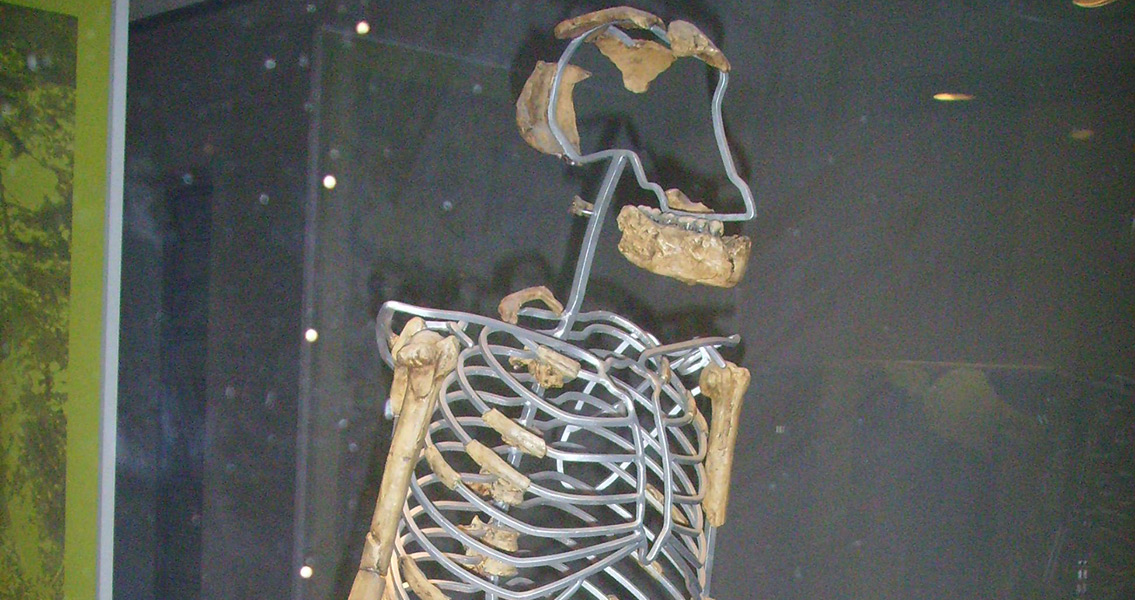

New Scientist. The debate may finally be settled based on the work completed by Christopher Ruff with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, along with his colleagues. Using CT scans taken of Lucy’s skeleton, they studied the cross sections of both (left and right) upper arm bones along with the left thigh bone — the thigh bone from the right leg was never found. What the team discovered was that Lucy’s arm bones had thick walls, suggesting unusual strength. Bone strength is considered a “use it or lose it” characteristic directly related to an animal’s behavior and not inherited; meaning that at least some australopiths were at home on the ground and in trees. “It would not be present unless Lucy mechanically loaded her upper limbs more than most modern humans,” Ruff told New Scientist. “Ours is the best evidence to date that A. afarensis actually spent a significant portion of their time engaged in arboreal behaviour.” Over the course of a person’s life, bone structure changes depending on the way we use, or don’t use, our bodies. Human thigh bones typically have thicker walls due to all of our walking, our arm bones however, have relatively thin walls because we seldom use them to carry or lift our full body weight. Chimpanzees on the other hand develop arms with thick-walled bones because of their tree climbing. Previously, Ruff and his team discovered injuries to Lucy’s skeleton that indicated she may have died from a high fall, most likely from a tree. That study also suggested that Lucy spent a significant amount of time climbing trees, but it was far from conclusive. “I could fall out of a tree and present the same injuries as they suggest Lucy had,” Harcourt-Smith says in the article. The study has been published in the online journal PLOS One. ]]>