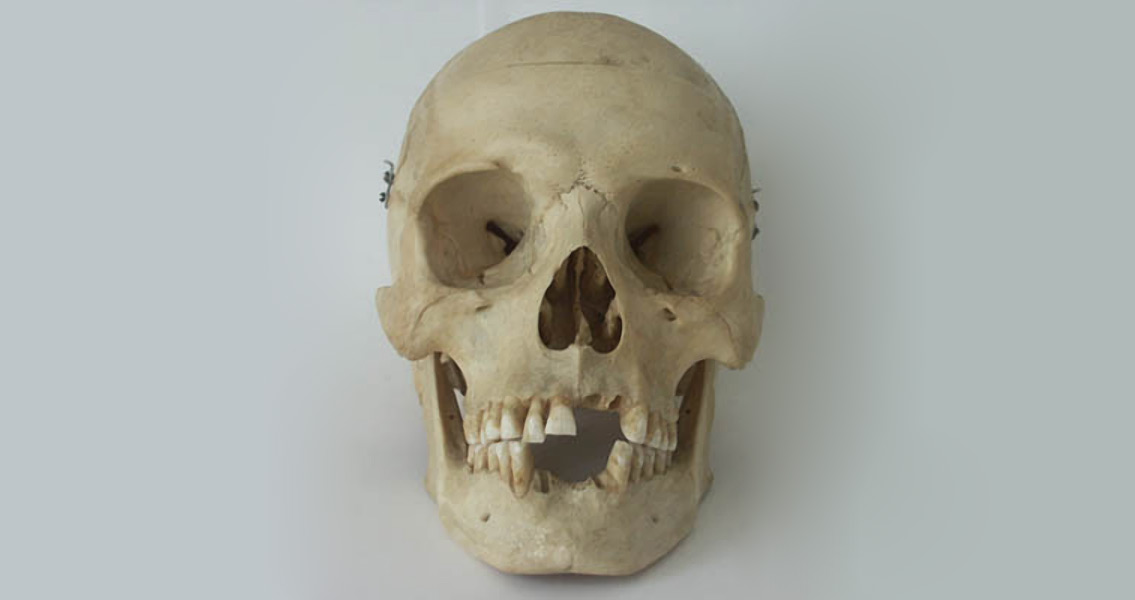

<![CDATA[A doctoral student from the University of Florida has forged a curious connection between ancient Maya living in Central America and the meteor impact that ended the reign of the dinosaurs. Ashley Sharpe, who graduates from the anthropology department of UF this fall semester, adapted a method used in forensic science to solve cold cases in order to create a map used to determine the birthplace of not just ancient people, but also ancient animals found in Central America. The process used by the map is unique in that it matches the type and amount of the mineral lead found in bedrock from particular Central American locations to ancient teeth. Being able to pinpoint the regions where prehistoric Maya were both born and died will aid researchers in unraveling the mysteries of the origins of the ancient civilization. Likewise, it could help throw new light on its mysterious decline. As part of her research, Sharpe took lead samples from rocks in the Yucatan Peninsula, specifically from the Chicxulub crater, the site of the meteor strike that catalyzed the extinction of the dinosaurs. The doctoral student analyzed the lead isotopes in these samples and then compared these results to places such as Honduras, Guatemala and Belize. An example of the research Sharpe gave in a recent press release involved finding a Maya who was buried in the Yucatan. Normally it might be impossible to determine where the individual had been born, but in doing a chemical analysis of the teeth of the Maya, it might be revealed that the lead isotopes in their teeth match that of Guatemala instead of Yucatan. The reason ancient teeth can be used in such a way is because the formation of tooth enamel during childhood years makes use of local environmental elements, up to and including the dust that might be inhaled from dirt and rock layers underfoot. Meanwhile, bones act much the opposite, soaking up geological elements after our deaths like sponges; the combination of the two can reveal, geologically, place of birth and place of death. Since tooth enamel is so very hard, it can be used to track the movement of individuals throughout their lifetimes, providing clues to things such as slavery practices and marriage alliances. Building up information about how individuals moved and migrated throughout their lives can help aid archaeologists in piecing together which villages were allied with one another and which they were opposed to, or how travel and communication was facilitated between Mayan cities. Sharpe remarked that the new technique could ultimately provide better insight into how different Maya states maintained their communication networks. Lead analysis such as Sharpe used was previously employed by UF forensic anthropologists to help identify anonymous victims of homicide by determining their place of birth. This can help law enforcement officials narrow their search parameters to particular regions, countries, or states. The university has also used the same or similar methods in tracking ancient Indus Valley humans. The new study, published in the journal PLOS ONE, can be found here]]>

The Curious Connection between Mayans and Dead Dinosaurs