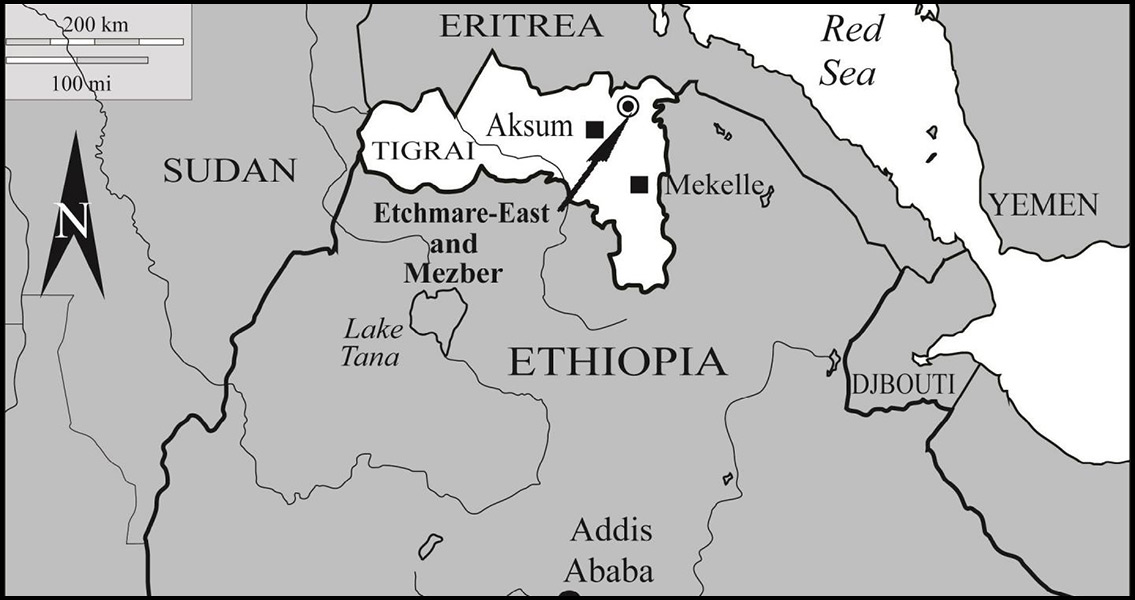

<![CDATA[Researchers have found some of the oldest known physical evidence of the introduction of domesticated chickens to the continent of Africa. The findings suggest the animals arrived on the continent centuries earlier than previously thought. The findings are providing fresh insight into ancient agricultural and trade contacts, showing how domesticated chickens crossed roads and seas to reach farms and kitchens in Africa. Most modern domestic chickens are descendants of the red junglefowl Gallus gallus, a species endemic to sub-Himalayan northern India, southern China and south-east China. First domesticated in the region between 6,000 and 8,000 years ago, the offspring of these chickens have spread across the globe. A team from Washington University in St. Louis radio carbon dated around 30 chicken bones unearthed from the site of an ancient farming village in what is today Ethiopia. Among them was a discarded chicken leg, etched with teeth marks from thousands of years ago. The bones provide physical evidence of the introduction of chickens to Africa. “Our study provides the earliest directly dated evidence for the presence of chickens in Africa and points to the significance of Red Sea and East African trade routes in the introduction of the chicken,” said Helina Woldekiros, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral anthropology researcher in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, in a press release. How the domesticated chicken arrived and then dispersed through Africa has long remained a mystery. Earlier research relied on depictions of chickens in ceramics and paintings, along with bones from other archaeological sites, to conclude that chickens were introduced to Africa through North Africa, Egypt and the Nile Valley about 2,500 years ago. Until now, the earliest actual bone based evidence of chickens in Africa was from the Saite levels at Buto, Egypt, and was dated to between 685 and 525 BCE. The new study, published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, both pushes that date back by centuries and also suggests that the initial introduction could have happened on the east rather than north coast of Africa. “Some of these bones were directly radiocarbon dated to 819-755 B.C., and with charcoal dates of 919-801 B.C. make these the earliest chickens in Africa,” explained Woldekiros. “They predate the earliest known Egyptian chickens by at least 300 years and highlight early exotic faunal exchanges in the Horn of Africa during the early first millennium B.C.” Co-author of the study Catherine D’Andrea, professor of archaeology at Simon Fraser University in Canada, led the excavation team in Ethiopia. The bones used in the study were recovered from the kitchen and living room floors of an ancient farming community known as Mezber: a rural village located in northern Ethiopia about 30 miles from the urban center of the pre-Aksumite civilization. The pre-Aksumites were the first people in the Horn of Africa to form complex, urban-rural trading networks. Interestingly, linguistic studies into the ancient root words for chickens in African languages suggest the birds had arrived through multiple routes: North Africa through the Sahara to West Africa; and from the East African coast to Central Africa. Molecular studies revealing the biodiversity of domesticated African chickens further support this notion of domestic chickens arriving in Africa through multiple routes. Woldekiros said: “It is likely that people brought chickens to Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa repeatedly over a long period of time: over 1,000 years. Our archaeological findings help to explain the genetic diversity of modern Africans chickens resulting from the introduction of diverse chicken lineages coming from early Arabian and South Asian context and later Swahili networks.” Studies like Woldekiros and D’Andrea’s shed new light on ancient migration, exchange and trade; the spread of domesticated animals tracing the paths of ancient connections. Sometimes these trades were unsuccessful of course, with various zooarchaeological studies showing examples where the introduction of a new species to a new part of the world failed. Other times it took repeated introductions of a new species to a region, something which the recently published study points to. “Our study also supports the African Red Sea coast as one possible early route of introduction of chickens to Africa and the Horn,” Woldekiros said. “It fits with ways in which maritime exchange networks were important for global distribution of chicken and other agricultural products. The early dates for chickens at Mezber, combined with their presence in all of the occupation phases at Mezber and in Aksumite contexts 40 B.C.- 600 A.D. in other parts of Ethiopia, demonstrate their long-term success in northern Ethiopia.” Image Courtesy of International Journal of Osteoarchaeology]]>

Domesticated Chickens Arrived In Africa Much Earlier than Thought