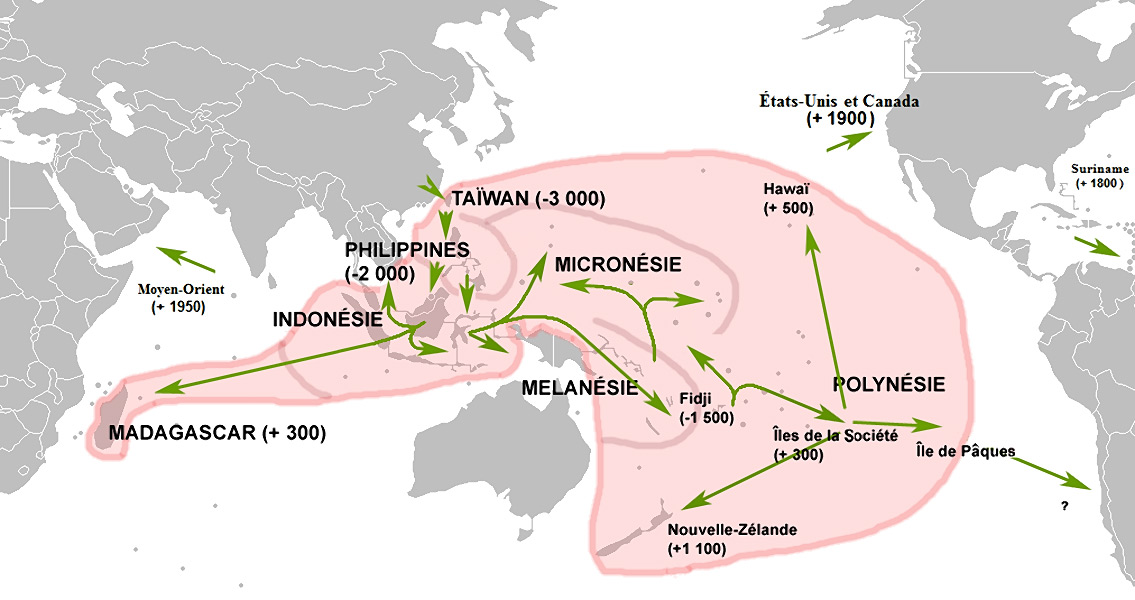

<![CDATA[The first humans to ever set foot on the remote Polynesian islands of the Pacific, including Fiji, did so just 3,000 years ago after sailing across thousands of kilometers of ocean. Although they left behind a distinctive type of red pottery, their identity has remained a mystery. Researchers have considered two possible scenarios: the first islanders were either people who interbred with the hunter-gatherers they met in Melanesia, including Papua New Guinea, on their way to Polynesia; or they were farmers who sailed directly to the isolated islands from mainland East Asia. Now, a new study describing the first genome-wide research of DNA taken from ancient Polynesians supports the non-stop option - that the ancient mariners who landed on the islands were East Asians who had been swept out to the Pacific and that the Melanesians, most likely males, headed out into Oceania much later to eventually mix with the Polynesians. A population geneticist with the University of Oxford (United Kingdom), Cristian Capelli explained in the publication Science that the study decides a decades-long dispute, showing the East Asians skipped over islands populated by Melanesians at the time without picking up any of their genes, an example of how cultures can initially avoid mixing between groups. Known collectively as the Lapita culture, the first Polynesian Islanders left behind plenty of enticing artifacts, including unique red stamped pottery, shell ornaments and obsidian tools. These artifacts first showed up over 3,000-years-ago in New Oceania, in the Bismarck Archipelago. The Lapita culture grew yams, taro and breadfruit; brought chickens and pigs; and quickly spread to other islands such as New Caledonia and Vanuatu, and then to Tonga, Samoa, Fiji, and beyond. The two models previously considered by archaeologists included the “express train” model, which had the Lapita traveling quickly from mainland China to Taiwan, the Philippines, and then across open ocean to Vanuatu and then Samoa. Covering a total of 24,300 kilometers in around 300 years. This model is supported by linguistics models showing how Austronesian languages, which are very different from the Papuan languages of Melanesia, spread into Oceania from East Asia. The “slow boat” model was supported by the DNA of live Polynesians which showed evidence of their Lapita ancestors lingering in Melanesia, living with the locals and then spreading slowly eastward. This new study involved the extraction of DNA from the ancient skeletons of four women from the islands Tonga and Vanuatu, dating back to between 2,300 and 3,100 years ago, three of which were directly connected to the Lapita culture. The international team sequenced the DNA (up to 231,000 positions) of each skeleton and then compared their findings to the DNA of almost 800 people from 83 different populations currently living in East Asia and Oceania. The four ancient women shared all of their ancestry with the Atayal, an indigenous people from Taiwan and the Kankanaey people from the Philippines. The Lapita showed no evidence of a Papuan ancestry, meaning they took the express route all the way to Oceania without ever mixing with Melanesians. ]]>

DNA Sequencing Proves First Polynesians Didn’t Linger on Their Journey