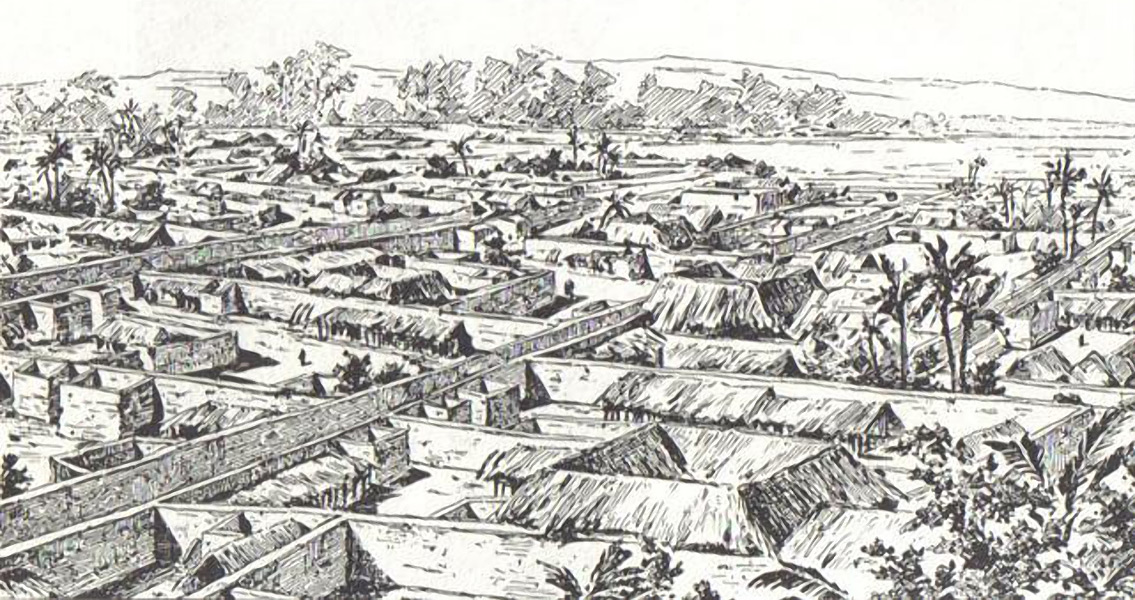

Modern estimates suggest that at one point the walls were four times longer than the Great Wall of China, using up to a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops. Beyond the city limits, further walls were constructed to divide the surroundings of the capital into around 500 distinct villages. This complicated network of walls was all dug by hand, the mosaic of settlement boundaries covering 6,500 sq. km in total. Huge metal lamps fueled by palm oil lined the city’s streets, a precursor to modern street lighting. When the Portuguese first laid eyes on the city in the middle of the jungle, they classified it as one of the most beautiful, well designed cities in the world. Lourenco Pinto, the captain of a Portuguese ship, observed in 1691: “Great Benin, where the King resides, is larger than Lisbon, all the streets run straight and as far as the eyes can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king which is richly decorated and has Fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such Security that they have no door to their houses.” Now, nothing of that city, believed to have been founded in 900 CE, remains. A new city has been built on the site, but no traces of the original’s unique splendor can be seen. The first centuries of European contact had seen Benin City enjoy a mutually beneficial trade relationship with Portugal. That all started to change in the nineteenth century, however, as Britain and other imperial powers upped their exploitation of Africa, moving from trading to the more profitable system of direct colonial take over. By 1884, chiefs of a plethora of tribes in the Niger Delta had signed treaties placing their people under the protection of the British crown. A protectorate government was set up with a headquarters in Calabar, and the area of British interest in the region continued to expand. By 1886 the activities of the Royal Niger Company had engulfed the area surrounding Benin, but the Oba (king) of Benin refused to sign up to the same treaties. For years Benin held out against many of the trading and other demands made by the British, yet the situation became increasingly perilous for the increasingly isolated kingdom. As Dr. Victor Osaro Edo wrote in 2009: “The fall of Benin from 1885 onwards became inevitable.” A trigger came in January 1897, when the Acting Consul-General in the region: James Phillips, led a large delegation to Benin City. The delegation hadn’t made their intentions clear and were making their visit during the Igue festival, when the Oba was not supposed to receive any visitors. What the expedition’s real intentions were is still debated, but Phillips’ unannounced arrival was seen as an invasion and intercepted by the Oba’s forces. In the ensuing battle, only two officers survived of the roughly 200 people in Phillips’ party. The retaliation by the British forces, known as the Benin Expedition, was swift and brutal. A large British force of 1,200 soldiers, at the time labelled the Punitive Expedition, was deployed. In February 1897, the machine gun bearing troops arrived at Benin, their orders were to conquer the city. Fierce fighting ensued, the Benin forces resisting for 17 days before the British expedition (including a large force of African recruits) took the Kingdom. What followed was a wave of destruction, the people of the city forced to flee as the invaders burnt it to the ground. The Oba’s palace was destroyed, while he was forced to live the rest of his life in exile in Calabar. The cultural relics of the city: ivory and bronze sculptures, were looted and then sold off to pay for the Benin Expedition. Today, around a thousand Benin bronzes can still be found in public and private collections around the globe, most notably in Britain but also elsewhere. These artefacts of the kingdom are relics of the achievements of the great city of Benin, and a powerful reminder of its fate at the hands of British imperialism. ]]>