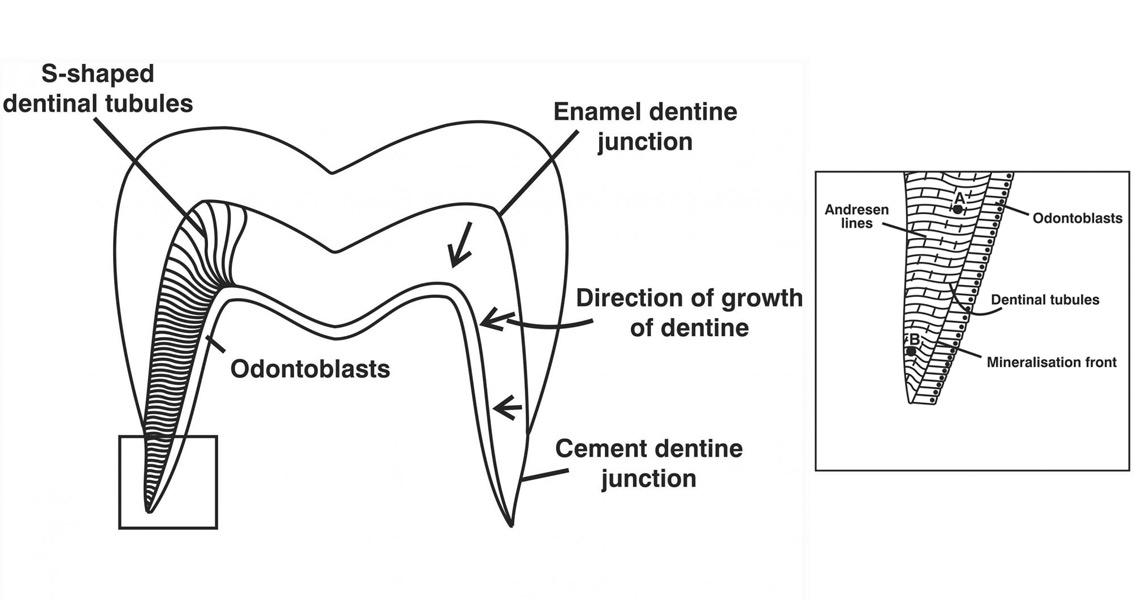

<![CDATA[The remains of several victims of the Great Irish Famine have been exposed to new analysis methods, revealing telltale signs of changes in diet as well as the prolonged stress the individuals experienced at the time. Spearheaded by the University of Bradford’s Julia Beaumont, the new study has the potential to identify signs of starvation in human tissues dating to at least the nineteenth century. Beaumont and her colleagues sampled a single tooth from twenty different residents of the Kilkenny Union workhouse, from both adults and children, and used isotopic analysis to analyze the nitrogen and carbon isotope ratios within the teeth. Researchers compared dentine collagen from small sections of the teeth, representative of the diet of the individual at the time the tooth was growing; with bone collagen taken from an individual’s ribs, which offers a record of the final years of life of each famine victim. The scientists then cross-referenced this data against food availability records dating to the nineteenth century. The results of their research did more than record the change in diet which saw the workhouse residents move away from potatoes and begin incorporating corn imported from America during relief efforts to help ameliorate the famine; it also showed evidence of long-term physiological stress, including nutritional stress as a result of not having enough to eat during childhood. These isotope analysis methods could play a role in identifying times of physiological stress, such as that caused by famine, in both adult and child populations, if the stress occurred while the subject’s teeth were still developing. The archaeological and forensic applications of these findings may aid in identifying both individuals and populations that experienced nutritional stress to the point of it playing a role in their demise, though the researchers say that additional work will be needed in order to further refine the process used to age the incremental collagen, according to a University of Bradford press release. Beaumont said that her team’s scientific analysis methods did produce detailed dietary histories, at least during the period of the subjects’ lives that their teeth were actively growing. With the workhouse residents being provided corn through famine relief efforts, the researcher added that her team was able to identify starvation markers in the teeth that were forming just prior to the change – something that has never before been seen in dentine. The Great Irish Famine, also known as the Great Hunger or the Irish Potato Famine, lasted from 1845 through 1852. Thought to be caused by a disease that ravaged potato crops during the middle of the nineteenth century, the famine had a particularly strong impact on Ireland due to how dependent the population had grown on potatoes as a nutritional staple and a cash crop. The famine reduced the population of Ireland by as much as 25 percent, through both emigration and death by starvation. The new research survey, published online in the journal PLOS ONE, can be found here Image courtesy of Beaumont et al. (2016) ]]>

Victims of Great Irish Famine Exposed to Tooth Analysis