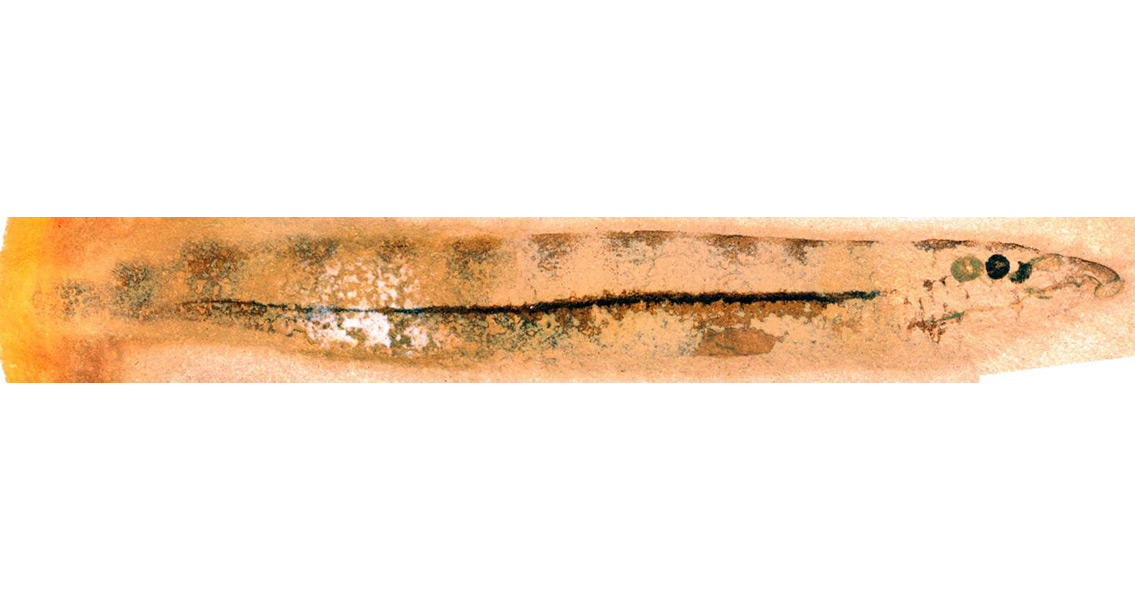

<![CDATA[New research, spearheaded by scientists from the University of Leicester, has been able to shed light on the evolutionary process behind the formation of sight in vertebrates, through the study of fossils. According to a university press release, Professor Sarah Gabbott led a team of researchers in studying 300-year-old fossilized hagfish and lamprey remains. The eyes of the fossil hagfish in particular were vastly different when compared to modern-day hagfish; while the modern hagfish (also known as the slime eel for its slime-producing properties) is completely blind, ancient hagfish had well-developed eyes, indicating that a “reverse” evolution had occurred over millions of years to rob the marine animal of its sight. Professor Gabbott’s team looked at both hagfish and lamprey fossils discovered in the Mazon Creek fossil bed in Illinois, dating to the Carboniferous age. The researchers examined the eye tissue in two fossil jawless fish species - Mayomyzon (a lamprey) and Myxinikela (a hagfish). Through the use of a scanning electron microscope, they studied the eyes under 5,000 times magnification, revealing melanosomes: minute structures that are present in human eyes and allow for clear focus and limit reflected light levels. This marks the first time that the eyes of fossilized vertebrates have been studied at such high resolutions. With the complexity of vision high, the evolution of sight is something that most scientists feel developed over small steps, but with the lack of any recorded data in living animals – and the belief up until now that it was impossible to see these details in fossils – the new research has helped to shed some much-needed light on an evolutionary process that has been otherwise occluded. Professor Gabbott explained: "To date models of vertebrate eye evolution focus only on living animals and the blind and 'rudimentary' hagfish eye was held-up as critical evidence of an intermediate stage in eye evolution. Living hagfish eyes appeared to sit between the simple light sensitive eye 'spots' of non-vertebrates and the sophisticated camera-style eyes of lampreys and most other vertebrates." But with the highly detailed images of the retina in fossilized hagfish, the evidence is high that the vertebrate could see quite clearly. This leads the researchers to believe that the eyes of living hagfish have lost their ability to see over the last 300 million years through evolution, and that the slime eel has not always been as simple and primitive a creature as traditionally thought. This makes modern hagfish a poor choice for studying the evolution of sight. The professor also remarked that with sight being arguably our most crucial sense, the evolution of eyes in vertebrates not only represents an enigma but also an often trotted-out argument in favor of Creationism. However, Professor Gabbott believes that this new method for examining fossilized eyes can open up the door for renewed scrutiny of other vertebrate fossils in order to build a better understanding of the evolution of vision. The new research study, published in the journal The Proceedings of the Royal Society B, can be found online here Image courtesy of Rober Sansom]]>

New Research on Evolution of the Eyes of Vertebrates