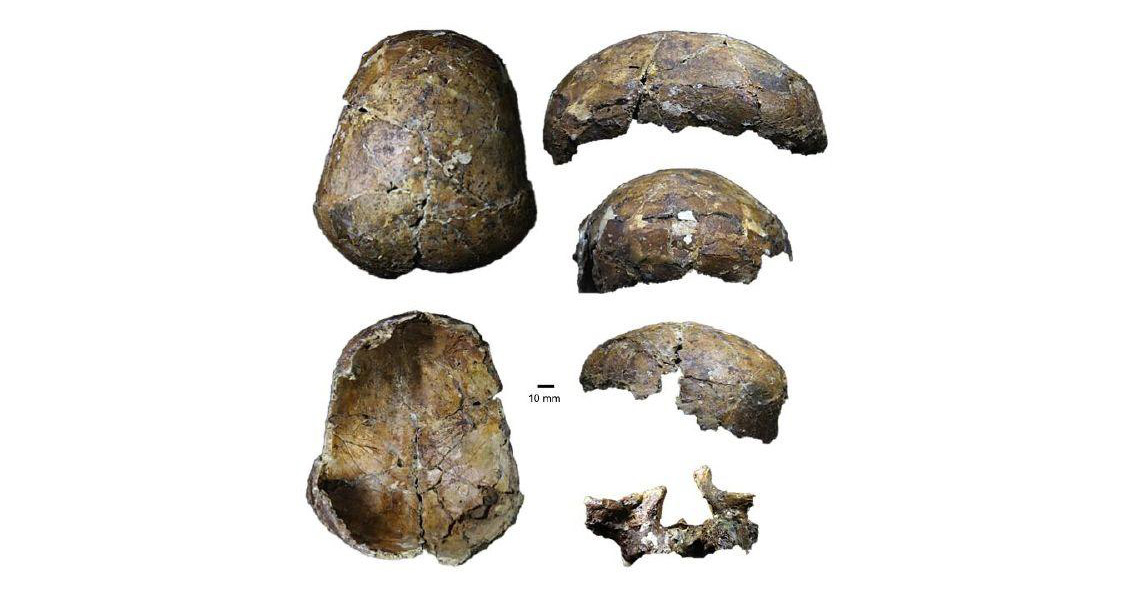

Ecology and Evolution, has brought this conclusion into question. Led by UNSW Australia Associate Professor Darren Curnoe, the research is the most comprehensive study of the skull since it was first found in the Niah Cave in Sarawak, Borneo, in 1958. “Our analysis overturns long-held views about the early history of this region,” said Associate Professor Curnoe, Director of the UNSW Palaeontology, Geobiology and Earth Archives Research Centre (PANGEA), in a press release from the University of New South Wales. “We’ve found that these very ancient remains most closely resemble some of the Indigenous people of Borneo today, with their delicately built features and small body size, rather than Indigenous people from Australia.” Among other revelations, the team have determined that the Deep Skull was likely to have belonged to a mature woman rather, than a teenage boy as previously believed. Scientists often advocate a ‘two layer hypothesis’ for the history of settlement in South-East Asia. This argues that the region was first settled tens of thousands of years ago by people related to Indigenous Australians and New Guineans. Farmers from southern China then preceded to migrate through and settle in the region, but only a few thousand years ago. The Deep Skull was considered major supporting evidence for this view, proof that 37,000 years ago the inhabitants of Borneo were similar to Indigenous Australians. The new study however, throws those assumptions up in the air. “Our discovery that the remains might well be the ancestors of Indigenous Bornean people is a game changer for the prehistory of South-East Asia.” explained Ipoi Datan, Director of the Sarawak Museum Department. The results suggest that, in Borneo at least, the people living there 37,000 years ago were much more like those who live there today, instead of Indigenous Australians. It also points to a long lasting continuity among the people who lived in the region, throwing serious doubt on the two layer hypothesis. “Our work, coupled with recent genetic studies of people across South-East Asia, presents a serious challenge to the two-layer scenario for Borneo and islands further to the north,” said Curnoe. Another ramification of the study is that the indigenous Borneans were not replaced by the migrating Chinese farmers, but instead adapted to the new farming culture when it arrived 3,000 years ago, further complicating our understanding of the prehistory of South-East Asia and raising questions about the dynamics at play during the processes of migration, settlement and resettlement. “We need to rethink our ideas about the region’s prehistory, which was far more complicated than we’ve appreciated until now.”, concluded Curnoe. Image courtesy of Curnoe]]>