<![CDATA[On 16th June 1958, Imre Nagy was hanged by communist authorities in Budapest. The former Hungarian Prime Minister who had become a leading figure in the 1956 Hungarian uprising was executed on the charge of treason. Nagy was born in Kaposvár, Hungary on 7th June 1896. Raised in a peasant family, he became a locksmith's apprentice at a young age before eventually joining the Austria-Hungarian forces fighting in the First World War. Nagy was captured by the Russian army, and while imprisoned joined the communists. By the time of the Russian Revolution, the future Hungarian Prime Minister had started to fight for the Red Army, helping the Bolsheviks overthrow the Tsarist regime. Following the end of the Russian Revolution, and the closing of the First World War, Nagy returned to his native Hungary. Serving in the short lived communist government of Bela Kun, Nagy was forced underground again in 1919 after Kun's government fell. As in much of Europe, a new fear of Communism spread to Hungary in the 1920s, making it increasingly dangerous to publicly advocate the ideology. By 1929 the situation had become too perilous, the Hungarian government continuing its clampdown on communists, and Nagy left for Moscow where he gained employment in the Institute for Agrarian Sciences. He remained in the Soviet Union until the end of the Second World War, when he returned to serve in the Soviet government of the newly occupied country. As minister of Agriculture, Nagy introduced substantial land reforms to Hungary in adherence to Soviet policy. Massive land estates were broken up and redistributed among the people of the country. Collectivisation was then applied to these farms, uniting the small plots of land in an attempt to pool resources and increase productivity. Although a long term and seemingly loyal follower of Soviet doctrine, Nagy soon started to find himself in opposition to the government in Moscow. In 1949 he was briefly expelled from the Hungarian Soviet Government for being too concerned with peasants' rights in the wake of Collectivisation. Nagy later made a public recantation, but the event revealed a willingness to question the authority of Moscow that would prove so important, and ultimately tragic, in later years. In 1953 Nagy was appointed Hungarian Prime Minister, suggesting he was still held in high regard in the Soviet Union. The situation would soon change dramatically. He reeled back the harshest extremes of Collectivisation, while encouraging the manufacture of more consumer goods. Nagy became an increasingly liberal dissenter in the uniform Soviet Republics; unsurprisingly, he was forced out of his role in 1955. He would return to the public eye soon after. On 23rd October 1956, in response to the Soviet Union's backlash against Nagy's liberal reforms, students and workers took to the streets of Budapest in protest. What started as demonstrations escalated into a full scale national revolt within a number of days. The Soviet government in Hungary could not deal with the mass protest, and quickly collapsed. Nagy, who had spent the interim working as a teacher, joined the revolt, and was soon nominated as Hungary's new premier through popular support. The response by the Soviet Union was a devastating one. 200,000 Soviet troops entered Hungary on 4th November and brought the revolution to a bloody halt. Nagy, who had attempted to install a new multi party system in the Hungarian government, desperately appealed to the United Nations for assistance, but it never came. He fled to the Yugoslav embassy for asylum, but was ultimately deceived into leaving under a false pledge of safe passage, and was quickly arrested. Tried and found guilty of treason in a secret trial, Nagy was executed on 16th June 1958 in Budapest; his body buried with little acknowledgment. 31 years later, on the anniversary of his death and with the Soviet Union collapsing, he was reburied with full honours at a massive ceremony in the Hungarian capital, attended by thousands of Hungarians. ]]>

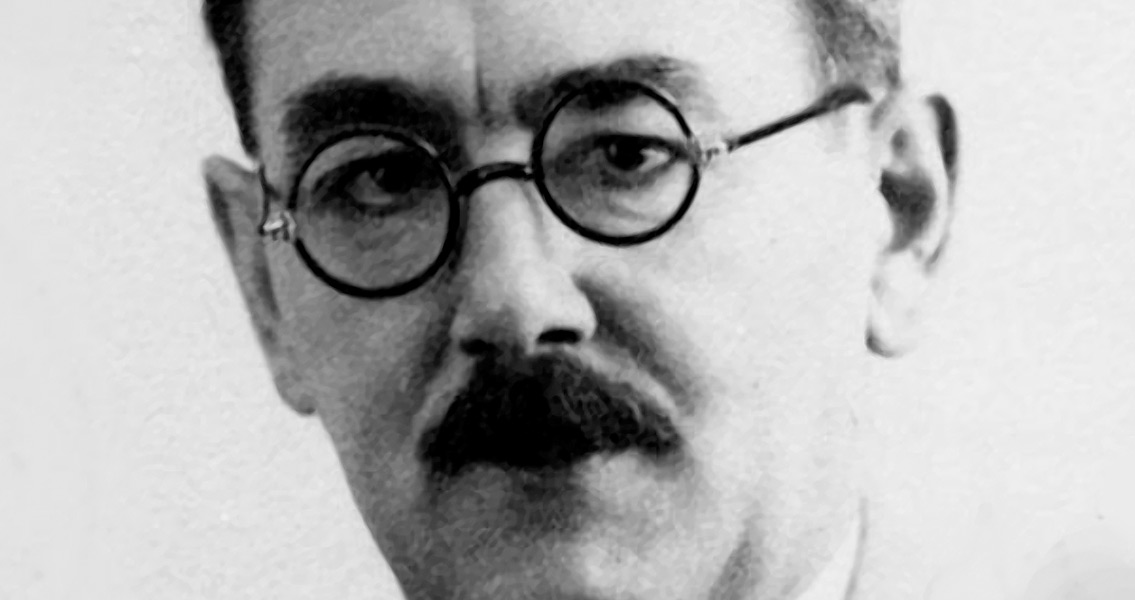

Imre Nagy Executed In Hungary