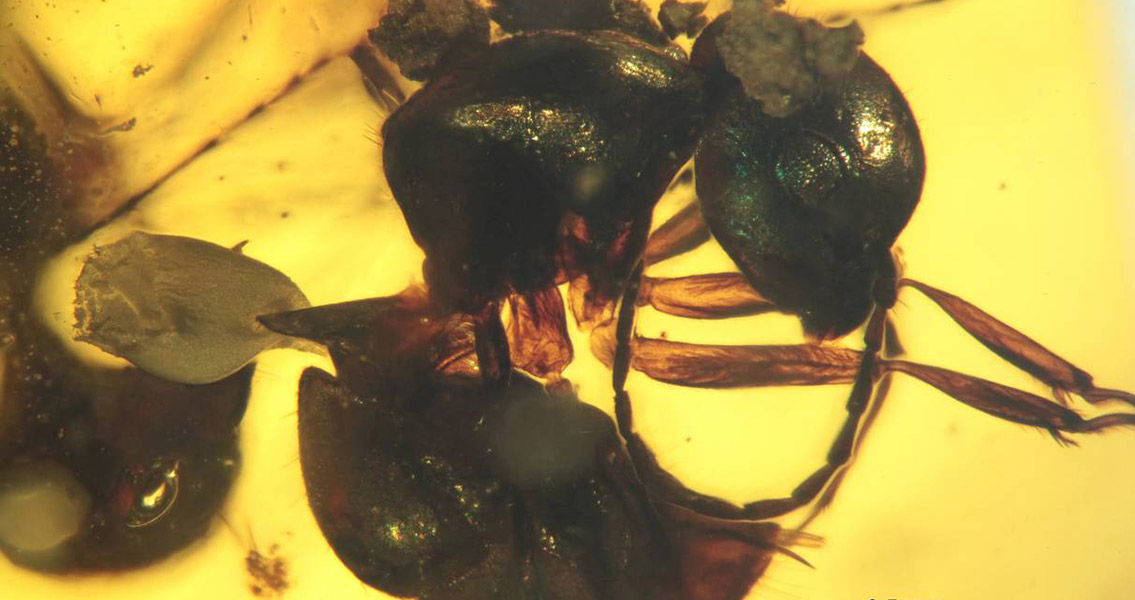

<![CDATA[New research into the fossilized remains of the ancestor species of ants dating to the Cretaceous has revealed the possibility of socially advanced behavior and group recruitment among these creatures. Ants, which diversified early within the Cretaceous, are just one of three highly organized, or eusocial, insects. Their success is, more or less, thought to be down to how organized and social their behavior is. Some studies have posited that early evolutionary branches may have resulted in the rise of small colonies of more solitary predator ants, but recent discoveries now suggest that the social levels of these early Cretaceous ancestors were already relatively advanced. A new ant species, found in a piece of Burmese amber dating to 99 million years ago, was discovered to have a rather prominent horn atop its head as well as extra-large mandibles resembling scythes, that extended high above the head. The new species, dubbed Ceratomyrmex ellenbergeri, is thought to have used its horn and mandibles to trap prey relatively large for its size. C. ellenbergeri, which belongs to the Formicidae stem-group, seems to be an exception to the idea of social evolution in Cretaceous ant species. The bladelike horizontal movement of the species’ mandibles are unique, resembling the Haidomyrmecine ants of the same time period which have long puzzled evolutionary biologists when it comes to classifying their ecology; both these species bear little in common with other large-mandible solitary hunter ant species such as modern trap-jaw ants. According to a press release from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, a new research paper spearheaded by Dr. Wang Bo from the academy’s Nanjing Institute of Geology and Paleontology found that C. ellenbergeri’s remarkable cephalic horn represents a hitherto unseen genetic modification among both ants discovered in the fossil record and the known ant species of today. This shows that the morphology of exaggerated trap-jaws such as in the Haidomymrmecines occurred early in the Formicidae stem group. The implications of the discovery include suggestions that at the very least some of the earliest Cretaceous stem-group ants differentiated themselves by being solitary socialist predators instead of eusocial insects. Additionally, the research study states that soon after ants started forming social bonds during the Early Cretaceous, there was at least one lineage in the form of Haidomyrmecini that grew to become effective at capturing prey – something that would not be seen in ant morphology again until well after the end of the Mesozoic, as evidence of these morphological specializations in the fossil record disappear for millions of years. The highly exaggerated features of the fossilized C. ellenbergeri specimen also show how early Cretaceous ants developed the ability to carry large-bodied prey, despite the fact that smaller prey would have presumably been easier to capture. In the end, the research data indicates that the earliest ants of the Cretaceous had ecological traits that were much more diversified and complex than previously thought. The research study, recently published in the journal Current Biology, can be found online here]]>

Evolution of Ants Laid Bare by New Fossil Discoveries