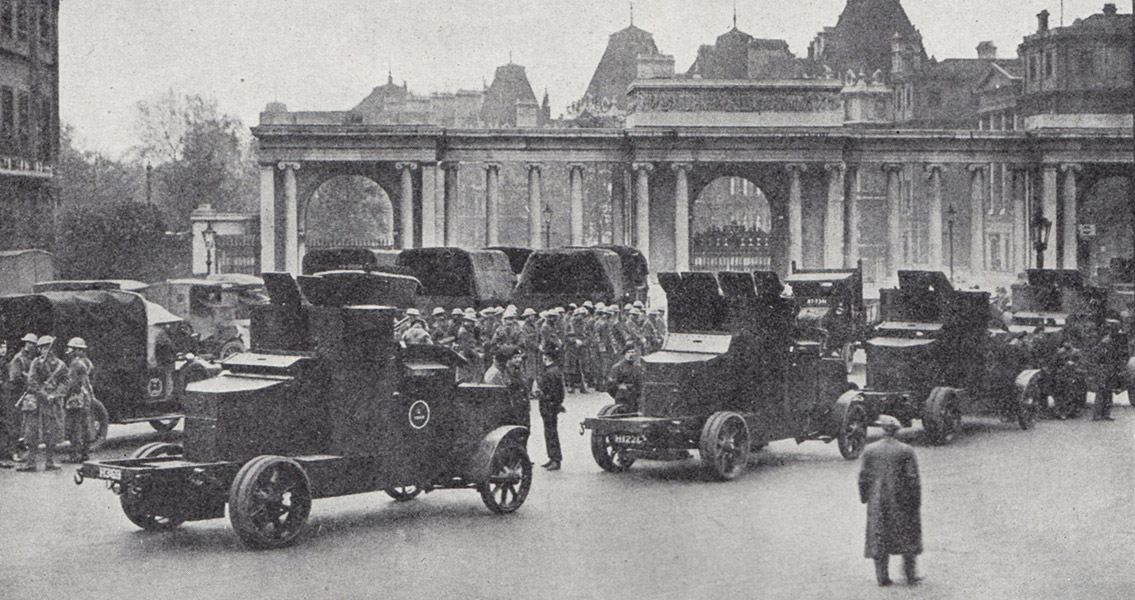

<![CDATA[Ninety years ago the biggest strike in British history started with a call to action by the Trade Union Congress (TUC). At a minute to midnight on 3rd May, 1926, the General Strike was declared. It marked a moment of solidarity across British industry, as workers downed tools in support of the nation's miners. Around a million coal miners had been locked out of their place of work at the start of May as a result of an industrial dispute, with no resolution in sight . The owners of the UK's mines wanted to reduce their employees' wages by 13% while at the same time increasing their daily hours from seven to eight. The first signs of the solidarity that would lead to the general strike came soon after, when workers at a press for the Daily Mail newspaper refused to print copies of a leading article criticising trade unions. The TUC called the massive strike across the British economy in the hope of forcing the government to intervene in the dispute and make the mine owners back down. Workers from the road transport, bus, rail, docks, printing, gas, electricity, building, iron, steel, chemicals and coal sectors all stayed off work as part of the strike. Since the late nineteenth century the relationship between labour and capital had been changing. General strikes in Belgium, Sweden and Germany had all set powerful precedents for workers' action, while the Russian Revolution stood as a shocking example of the power of labour, an inspiration for some but a source of growing fear for the establishment. Economic turmoil in the aftermath of the First World War fueled growing unionisation, and growing despair among the UK's workers. The war had taken a horrendous toll on those sent to fight, in deaths and injury, and those fortunate enough to return home were left dissatisfied with poor working conditions and inequality. The struggling British economy meant the situation showed little sign of improving, causing a series of strikes and protests. The decision by the British government to return the pound to the gold standard in 1925 triggered a full blown depression in the United Kingdom, one that particularly hurt the mining industry as it reduced the amount of coal exports from the UK. This combination of prolonged dissatisfaction with the post-War world and in the short term a severe economic depression caused by the actions of the government proved pivotal in pushing the UK towards the General Strike. Some two million workers from across the United Kingdom went on strike from the early hours of 3rd May. The goal was to bring the country to a standstill, in particular London, placing huge pressure on the government to act to keep the business centre running. The government responded by deploying the army to ensure essential services still ran and food and water supplies got through the blockades. Ultimately, the fear of communism proved to be more powerful than perhaps the TUC had expected. From non-unionised workers to university students, members of the general public decided to get involved to keep the country running, driving trams, buses and delivery vans, even going so far as assisting in power plants. Violent clashes occurred between police and strikers in several cities. In many cases these battles in the streets were caused at least in part by officers rushing the strikers. Nevertheless, the image it gave off was a strong one, of the General Strike having led to anarchy and lawlessness on the UK's streets. On 11th May the TUC called off the General Strike, leaving the miners to continue their protest alone. By November they had been defeated and were forced to accept the increased hours and reduced pay. Two years later, legislation was passed which made general strikes illegal. A combination of fear of communism pushed by the government and the media, alongisde alienation of the middle class to the striker's cause, saw the effectiveness of the 1926 general strike greatly restricted, and marked the start of increasingly widespread anti-union sentiment in the UK. ]]>

Ninetieth Anniversary of the General Strike in the UK