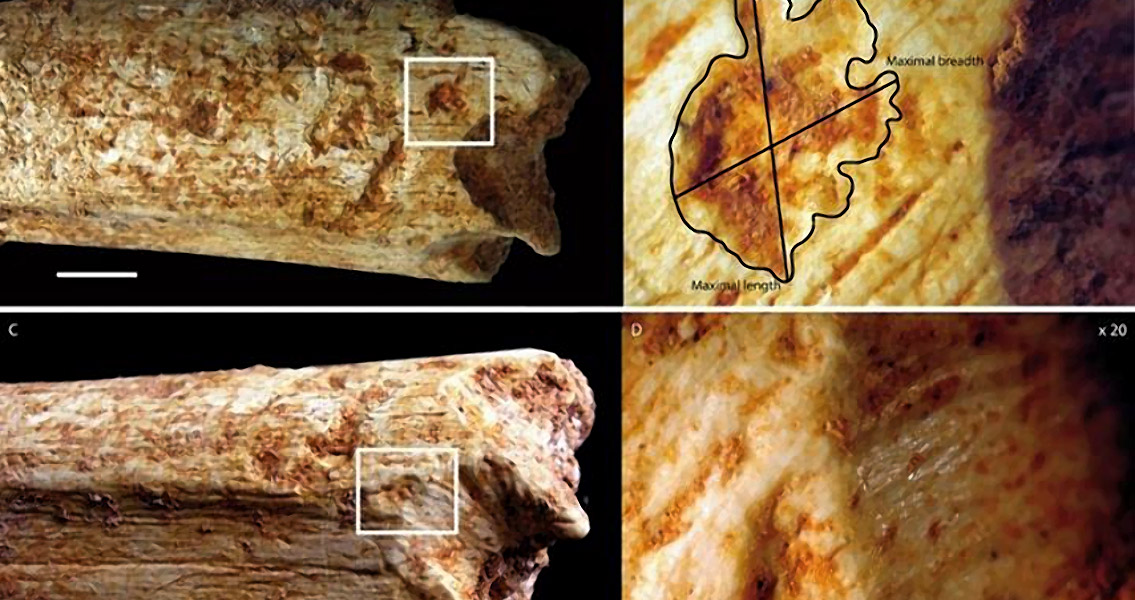

<![CDATA[The femur bone of a 500,000 year old hominin, discovered in a cave in Morocco, bears telltale tooth marks – making a case for large carnivores having preyed upon these hominins during prehistory. In a new research study published recently on behalf of France’s Muséum National D'Histoire Naturelle, head researcher Camille Daujeard and colleagues say that in this instance, a large carnivore such as a hyena likely snacked on this early human specimen. Hominins living during the time – the Middle Pleistocene – would have been in competition for resources and living space with these large carnivores as their territories would have overlapped, but little in the way of evidence has been found to indicate any interaction between carnivores and early humans – until now. Evidence of consumption by large carnivores is unmistakable, according to the study authors, who examined the 500,000 year old hominin leg bone. The skeletal remains were discovered near Casablanca in a cave system known as the "Grotte à Hominidés". The notches, scores, and tooth pits found on the bone, along with the various fractures present on the femur as well, were mostly located at the two terminal ends, as the softer areas of the femur had been completely crushed – ostensibly through the repeated chewing and gnawing of predators, much in the same way that a pet dog might chew a rawhide bone today. The researchers say that the marks and their appearance strongly indicate that they were likely placed there shortly after the death of the hominin, and that they were the result of a carnivore species such as a hyena. However, the research team said that it was impossible to rule out other possibilities, such as the bone having been scavenged long after the death of the early human or the hominin having been hunted and killed by a hyena – or pack of hyenas – directly. Regardless of the early human’s cause of death, the tooth marks on its femur present the first solid evidence that hominins were eaten by large carnivores during the Middle Pleistocene – at least in Morocco. This contradicts other evidence from the time that has indicated early humans might have turned the tables on carnivores, hunting and eating them in turn. The researchers say this could represent a circumstance where hominins might have been active in both roles at once – both of hunter and hunted, depending on situational circumstances. In a press release accompanying the publication of the new research study, Daujeard remarked that while confrontations and other types of encounters between early humans and large carnivores during the Middle Pleistocene were likely quite common, the new discovery is one of only a handful of examples where it has been proven that large carnivores in North Africa did indeed consume hominins. The research study is available online from the journal PLOS ONE Image courtesy of C. Daujeard PLOS ONE e0152284]]>

Large Carnivores May Have Eaten Ancient Hominins