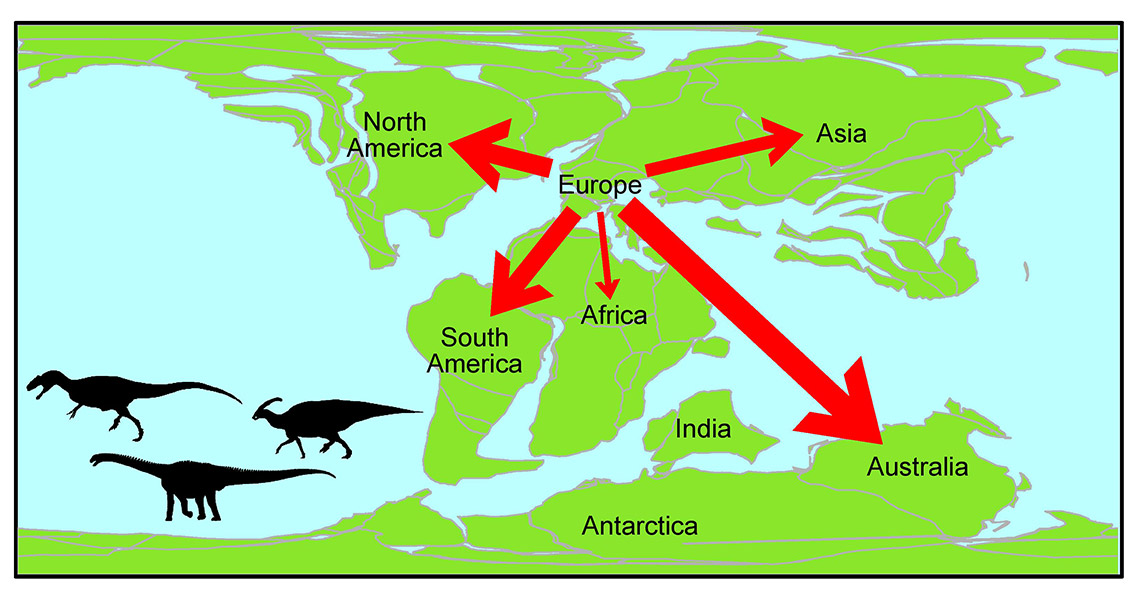

<![CDATA[The curiosity of paleontologists has been piqued by a new research study revealing a strange so-called exodus of dinosaur species from Europe during the Early Cretaceous period over 100 million years ago. Previous studies of global dinosaur migration patterns have already found that these creatures continued their migration across the globe well after Pangaea, the so-called “supercontinent” caused by tectonic shift, began to drift apart into the separate land masses that we’re familiar with today. Temporary land-bridges between these continents are likely to have facilitated these migrations, with sea level changes forming and maintaining these passages for long enough periods of time to spread dinosaur species to these slowly drifting continents. It is hard to imagine such massive structures, says the University of Leeds’ Dr Alex Dunhill, the lead author of the study. In a recent press release the head researcher remarked that these land bridges could have connected continents and subcontinents for tens of millions of years at a time, and that the conditions that would have formed these land bridges would have been “perfectly feasible” based on what scientists know of plate tectonics during the time. The research study’s main purpose was to investigate whether these migratory patterns were influenced overall by continental drift. The team’s findings do support the idea that intercontinental dinosaur migration did continue to occur during this period, even though the volume of migration decreased thanks to the limited opportunities for dinosaur species to travel on foot to regions that were rapidly separating. However, one discovery the scientists made was an unexpected one. When it came to Europe – or the region of the post-Pangaea world that would one day become Europe – migratory records indicate that the region underwent one-way movement. In other words, dinosaur species were found to have exclusively been leaving Europe during the Early Cretaceous, bound for other continents. There were no different dinosaur species moving back in to fill the void. There’s no concrete explanation for these “curious” results, stated Dr. Dunhill. He posited that while the possibility exists that this could be a legitimate migratory pattern, it could also have been the result of a statistical artifact or perhaps even due to a hole in the dinosaur fossil record – something that is a possibility, based on its sporadic and incomplete nature. The study made exclusive use of the Paleobiology Database, a massive data collection that contains information on every accessible and documented dinosaur fossil across the globe. The researchers made use of network theory to quantify this data – a first for biological research although network theory is routinely used for internet data such as social media trends – and then filtered it carefully to reduce misleading data caused by disparities in the fossil record. There still exists the possibility that the strange European exodus could be a statistical anomaly, however. Dr. James Sciberras, the study’s co-author from the University of Bath, remarked that there is precedent in using network theory in other disciplines, pointing out that physics has made use of the technique for several years. Dr. Sciberras was enthusiastic about the opportunities that the application of network theory could bring to a wide array of academic fields. For more information: www.onlinelibrary.wiley.com Image courtesy of Alex Dunhill, University of Leeds ]]>

Dinosaur Movement Research Reveals European Exodus