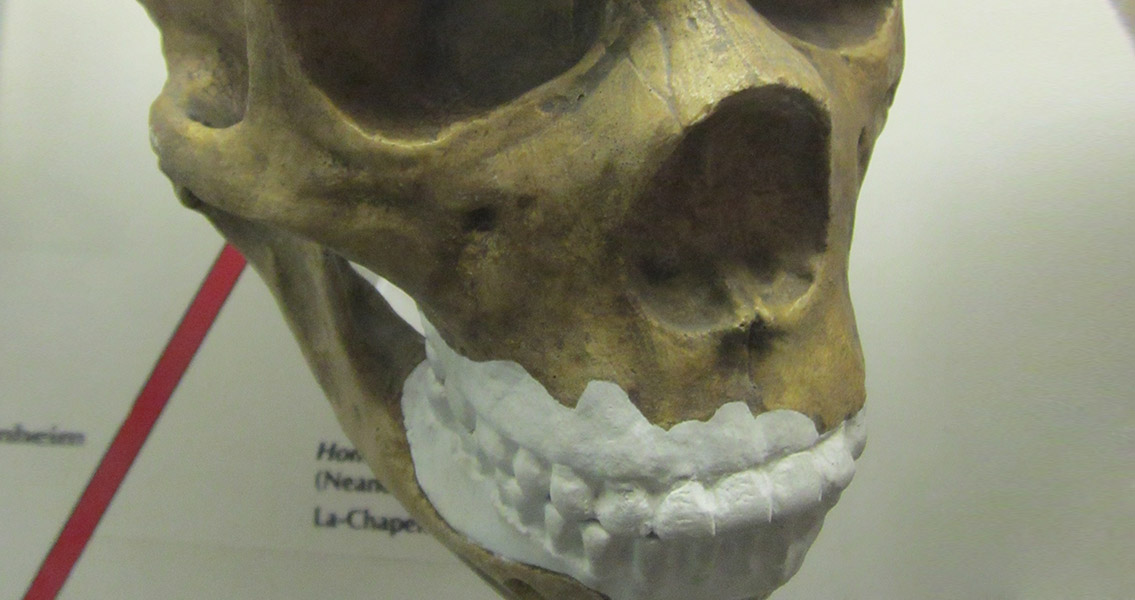

<![CDATA[The Neanderthals, our closest extinct relatives, are a constant source of fascination. The marks of their lives can be seen in fossil sites across Europe and Asia, yet just how similar we are to our ancient cousins, and the relationship our ancestors had with them, are shrouded in obscurity. A new study, published in the journal Antiquity, has discovered evidence of non-edible material in Neanderthal teeth. It is a remarkable find, one which opens up a host of possibilities concerning what Neanderthals did with their teeth: did they use their mouths as a third hand, or are the non-edible materials evidence that Neanderthals were concerned with dental hygiene? Most estimates suggest that Neanderthals first came on the scene between 300,000 and 250,000 years ago. By around 32,000 years ago they had been rendered completely extinct. They are often portrayed as being less intelligent, and uncivilised when compared to humans, however, new studies, including this latest one by Anita Radinia, Stephen Buckleya, Antonio Rosasa, Almudena Estalrricha, Marco de la Rasillaa and Karen Hardy; are increasingly bringing this assumption into question. For their research, the team led by Hardy from the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies extracted chemical compounds and micro fossils embedded in the teeth of Neanderthals from the 49,000 year old El Sidrón site in Spain. It was a unique approach to the still relatively new use of dental calculus (tartar) in archaeological study. Dental calculus is a hard substance that builds up on a creature’s teeth when they are not cleaned properly. For a long time archaeologists considered it nothing more than a waste product, and scrubbed it off of fossils. Over the last decade however, it’s been realised calculus actually contains a wealth of information, particularly when it comes to diet reconstruction of ancient populations. Hardy’s team discovered traces of conifer wood from a non-edible part of the trees in the molar of one adult Neanderthal. According to the study, the substance with no nutritional value could not have been confused with an edible part of a conifer – meaning it’s presence was certainly not connected to the Neanderthal’s diet. The study, published in the April edition of Antiquity, points out that associated dental wear suggests the teeth were being used for non-dietary functions, supporting the idea the piece of conifer had become embedded in the molar because the animal was using its mouth as a third hand. However, there are several other possible explanations. A study from 2013 revealed evidence from a 1.8 million year old Homo Erectus fossil discovered in Georgia that the creature had used something resembling a tooth pick to clean its teeth. Another study published earlier this year in the Journal of Human Evolution suggested that Neanderthals had healthier teeth than modern human hunter gatherers, a result of them cleaning their teeth. Taking these two studies into consideration, the piece of conifer wood in the El Sidrón Neanderthal’s teeth could have been linked to dental hygiene. Hardy et al’s study shows that a wealth of new insights into the lives of Neanderthals and ancient humans can be gained by studying dental calculus. The ambiguity surrounding their discovery serves as a reminder of just how much there is to learn about how our extinct cousins lived. For more information: journals.cambridge.org Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons user: Rept0n1x]]>

Did Neanderthals Brush Their Teeth?