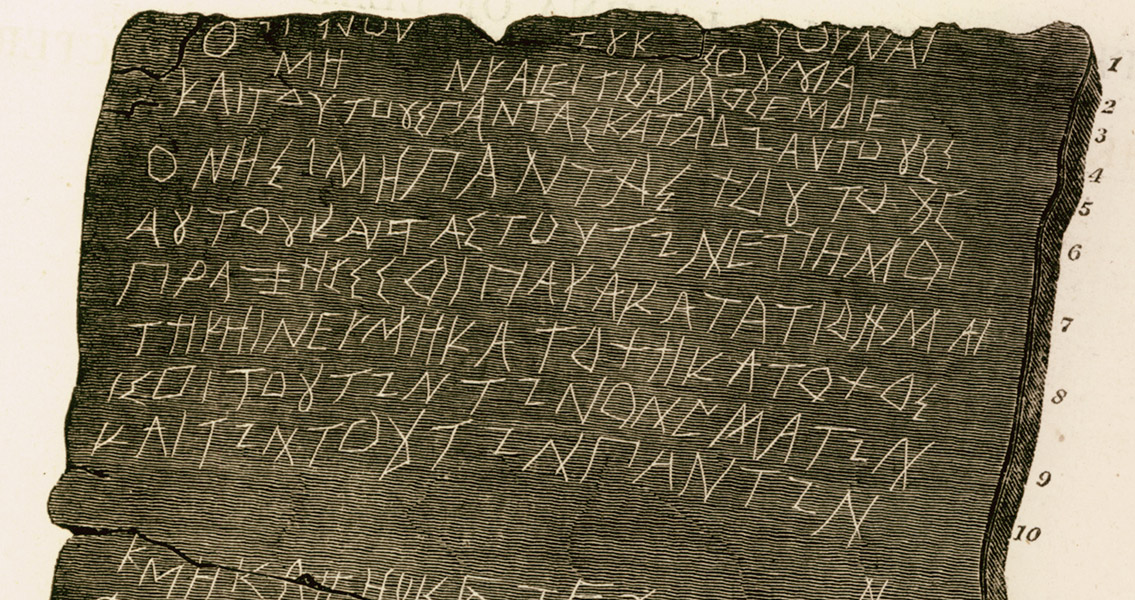

<![CDATA[A handful of lead tablets, several of which were inscribed with poison-tongued curses, have been found in the grave of a young Athenian woman in Greece. Of the five tablets, only one was blank; the other four were dedicated by name to various gods of the underworld. These inscribed tablets beseeched these chthonic mythological entities to curse a quartet of Athenian tavern keepers, all pairs of husband-and-wife teams. The blank tablet, scientists say, had been used as a ritual focus for an oral incantation of yet another curse, and was purposefully buried without inscription. All five of the curse-riddled tablets had iron nails driven through them and then folded over before being interred with the remains of the woman approximately 2,400 years ago in an effort to reach the gods of the underworld. The curses themselves leave little to the imagination. One of the tablets, translated from the Greek, calls for the gods to “cast [their] hate” down on Demetrios and Phanagora, two tavern keepers, and asked for them to be bound “in blood and in ashes, with all the dead.” The curse called for a kynotos to bind Demetrios’ tongue; kynotos, which translates to “dog’s ear”, was an ancient term for a common game of chance. Analogous to rolling snake eyes on a modern pair of dice, the dog’s ear was the worst roll one could make, according to an interview in Live Science with Jessica Lamont from John Hopkins University, one of the researchers involved in studying the curse tablets. Lamont further commented on the language of the curse and the ritual nature of pounding a nail through the tablet. Entreating the gods to strike the tavern-keeper’s tongue with a dog’s ear shows how important gambling and games of chance were to the economic success of Athenian taverns, she said – and that hammered nail through the curse would have been a ritual echo, intended to drive home the request to the gods in a forceful manner. Discovered in 2003 by archaeologists investigating a dig site outside Piraeus, Athens’ port region, the contents of the grave have been since relocated to the Piraeus Museum. Lamont, who traveled to the museum in order to study the curse tablets, stated that the results of the archaeological dig have yet to be published, but she was able to confirm that the tablets accompanied the cremated remains of a young Athenian woman. Contemporary belief dictated that curse tablets would only work when deposited underground in a well, a grave, or some similar location, the researcher recounted. Such locations would have provided a direct line for the curses to reach the chthonic underworld gods, and once these curses reached the ears of these entities, they would enact them. In fact, Lamont says that the grave and its occupant may have had nothing to do with the curses. The possibility exists the grave site, which would have been open and accessible during Greek funerary rites, was simply a convenient place to ensure the tablets reached the underworld. While the originator of the curses was most likely a rival tavern-keeper looking for a supernatural leg up on his or her competition, the eloquence of the curses themselves indicates they were written by a professional – someone who would have provided a number of services such as spells and charms to paying customers. The full text of Lamont’s curse tablet research can be found here]]>

Ancient Lead Curse Tablets Discovered in Grave in Athens