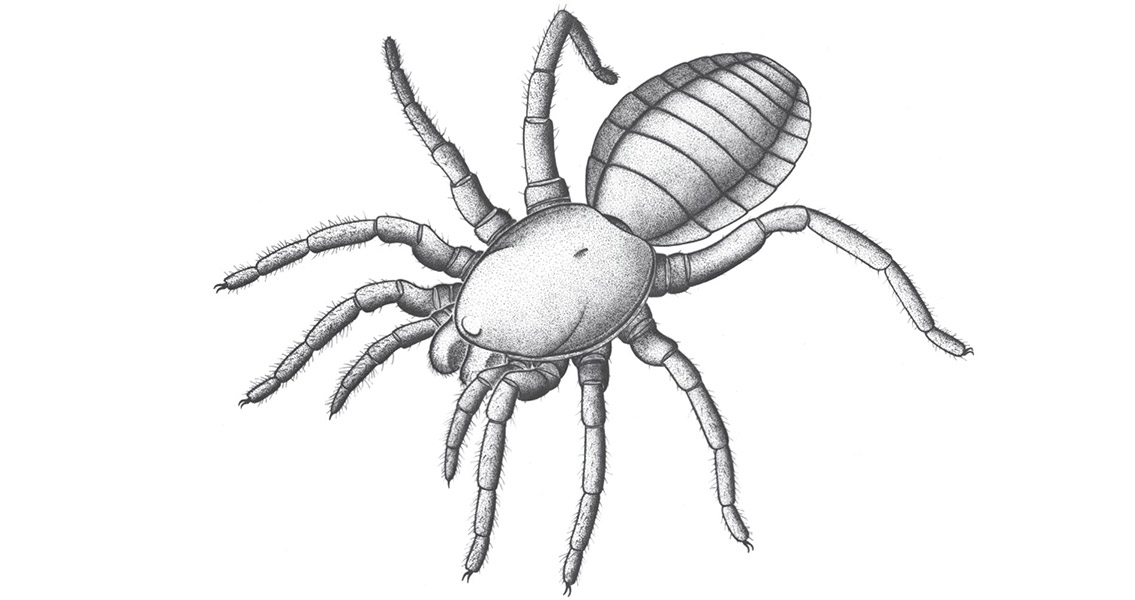

<![CDATA[The remains of a fossilized creature dated to around 305 million years old is a case of “close but no cigar” when it comes to being classified as a spider, scientists say. In order for creatures to be considered modern spiders they need to possess a number of specific characteristics. These include the requisite number of legs, specifically shaped mouthparts, and other requirements like a segmented abdomen. This new fossil, sadly, ticks all but one of the boxes required – it’s missing the spinnerets that spiders use to produce the silk needed to spin webs. Alas, the new creature has to live with the classification of arachnid, an order that includes creatures such as scorpions, ticks, mites and other related insects. Spiders are also a part of the arachnid order – but such as not all rectangles are squares, not all arachnids are spiders. However, classifying this arachnid as a “new” find is also disingenuous – the existence of the fossil has been known for decades. However, it was impossible to study as the fossil’s front half was embedded in solid rock. It remained unidentified until recently, when University of Manchester paleontologist Russell Garwood and his colleagues subjected the fossil to computed tomography (CT) scanning, completing the mystery of what lay occluded in the rock. Garwood, in an interview with Live Science, said that this particular arachnid species has been named Idmonarachne brasieri as a nod to Idmon, the father of Arachne from Greek mythology – the woman who was transformed into a spider out of the jealousy of the goddess Athena. With the process of evolution producing an arachnid just one step removed from a “true” spider, naming I. brasieri in such a manner seems highly appropriate. The evolutionary journey from arachnid to spider is further complicated by the fact that there is evidence of true spiders living alongside their almost-spider arachnid relatives. The oldest known spider fossil, discovered in eastern France at a Montceau-les-Mines coal seam, also happens to be 305 million years of age. Garwood remarked that this shows an arachnid subspecies that were nearly identical to spiders – though one that eventually died off – likely split from a common ancestor before that date. It has been difficult to pin down the origins and evolutionary pathways of arachnids, said Garwood. One of the first species to dwell on land, arachnids – or their progenitors – began to adopt a terrestrial way of life 420 million years in the past; little of this early history has been recorded in the fossil record. Meanwhile, using DNA analysis to trace the evolutionary relationships between arachnid species also presents difficulties due to the rapid diversification of the creatures. This has resulted in little to no evolutionary changes in their genetics that can be traced. The results are that there is little in the way of knowledge when it comes to how other arachnids like scorpions and spiders are interrelated in the overall scheme of evolution. Garwood and his colleagues say that there are plans to continue to study arachnid fossils in an attempt to glean more information on their mysterious origins. Image courtesy of Garwood, Russell J.; Dunlop, Jason A.; Selden, Paul A.; Spencer, Alan R.T.; Atwood, Robert C.; Vo, Nghia T. & Drakopoulos, Michael (2016)]]>

305 Million Year Old “Almost Spider” Remains Found