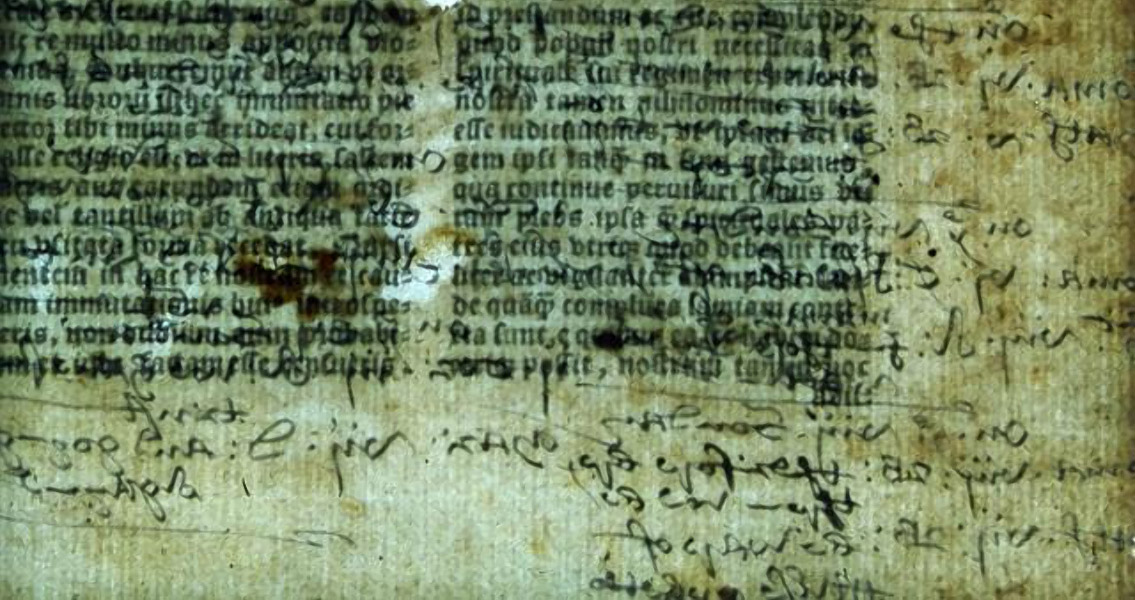

<![CDATA[Cleverly hidden annotations have been discovered in the first Bible ever printed in England, created by none other than Henry VIII’s personal printer in 1535. There are only seven copies remaining of the 1535 Bible, and very little is known about the circumstances surrounding its printing save for the fact that Henry himself penned the preface. The particular copy involved in the discovery, held under lock and key in London’s Lambeth Palace Library, was subjected to study by Dr. Eyal Poleg, a Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) historian. Originally, Dr. Poleg found nothing of importance about the Lambeth copy that stood out in comparison to the others. In a press release from the university, the historian remarked that he noticed a curious fact upon closer physical inspection of the manuscript – that there had been heavy-gauge paper pasted over certain parts of the book, especially blank parts. It would be a challenge to access these annotations without risking damage to the historic text. Dr. Poleg sought out a fellow QMUL researcher in the form of Dr. Graham Davis of the university’s School of Dentistry. Dr. Davis, who specializes in 3D x-ray imaging, was able to slide a light sheet beneath the pages and take a pair of long exposure images, one with the light sheet illuminating the pages from below and one with the sheet off – to reveal the hidden annotations. The illuminated image displayed not just the annotations themselves but the printed text in a jumble that made it nearly impossible to decipher. However, thanks to the second exposure which showed the printed text exclusively, Dr. Davis was able to filter out the printed text by creating a computer program that isolated the annotations in order to make them readable. The researchers were able to identify the annotations as being copied from Thomas Cromwell’s “Great Bible,” a series of English Reformation Bibles that were produced for around a decade starting in 1539. These annotations were purposefully disguised in 1600 by covering them with thick paper, hidden from view for more than four centuries. Dr. Poleg points out that the presence of the annotations indicates that the Reformation was not a single event that transformed English religious life, but a more gradual process that took its time to work. Less like a single moment akin to Caesar crossing the Rubicon and more a complex and slow process. The English annotations combined together with the Latin of the original Bible show how the nation slowly adopted Protestantism instead of simply renouncing Catholicism in one fell swoop. Additional discoveries made by Dr. Poleg included tracing the path the book took through subsequent owners as the popularity of Latin Bibles began to decline. A handwritten transaction on the back page of the text, hidden once more by the thick paper, contained a record of sale between one owner, Mr. William Cheffyn of Calais, and the prospective buyer, a Mr. James Elys Cutpurse of London, for the sum of 20 shillings. With Dr. Poleg discovering that Cutpurse had been executed by hanging in Tybourn in the July of 1552, the historian says this makes it easy to pinpoint a window as to when the sale actually occurred. Image courtesy of ©Lambeth Palace Library ]]>

England’s First Printed Bible Holds Secret Annotations