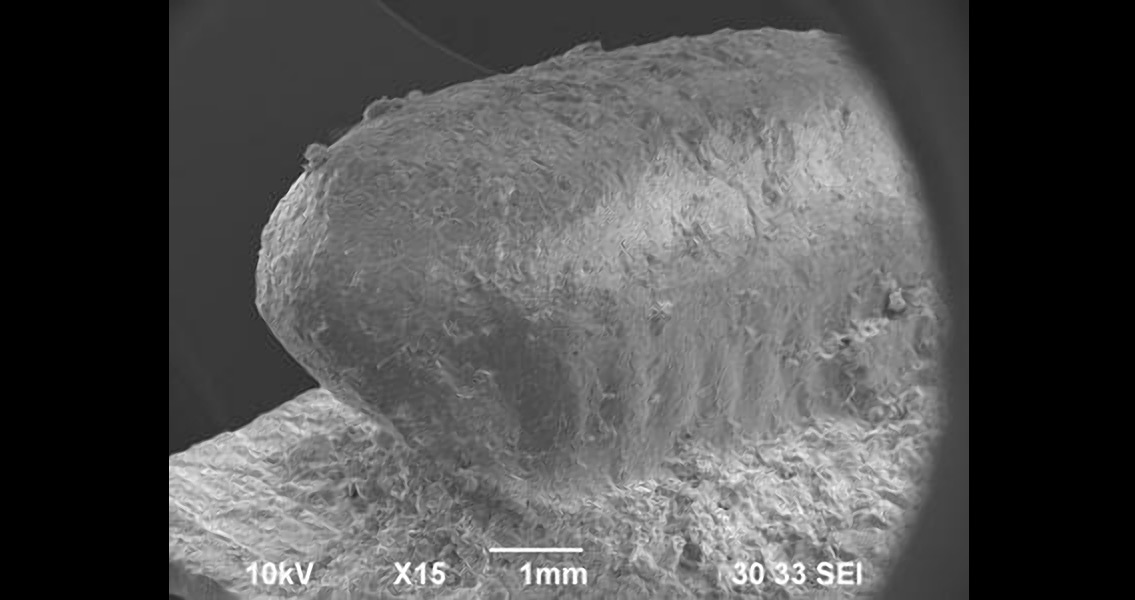

<![CDATA[Impressions of Japanese cockroach egg cases were recently found in broken fragments of pottery dating back to the Jomon Period around 4,300 years ago, scientists say. A new research study from Kumamoto University used CT, X-ray and scanning electron microscope analysis to reveal the telltale marks of egg cases left behind on the ancient potsherds, unearthed at a dig site in southern Japan. Normally, the discovery of ancient pottery is noteworthy for what might be still inside the earthenware, yet in this case the pots themselves were the treasure, according to archaeologist Hiroki Obata, a professor at Kumamoto University who was involved in the study. It’s only been about 25 years that the importance of impressions left behind on recovered potsherds has been known, Professor Obata added, stating in a press release from the university that these vacant holes on the surface of the fragments can help researchers glean information on shells, insects, nuts, seeds, or any other number of objects from the past. Data extrapolated from the impressions left behind by adzuki beans or soybeans mixed in the clay during the creation of a vessel, for example, can help pinpoint when these crops began to be cultivated in the region – which makes studying these impressions crucial in the effort to gather anthropological information about the individuals who lived in the area in the past. In this case, examinations of silicon molds made from the potsherds revealed 11 millimeter-long egg case impressions from Periplaneta fulginosa, more well known as the smokybrown cockroach. Native to southern China, P. fulginosa is depicted in Japanese artwork and literature from the Edo Period of the eighteenth century. Previously, the cockroach species was considered a domestic one from the Edo Period forward based on Japanese cultural evidence, but with these potsherds dating back to at least 4,000 years in the past, it now seems certain that P. fulginosa has been present in Japan for much longer than originally thought. This isn’t the first time Obata and his team has made an insect-based discovery by examining the impressions left behind on ancient Japanese pottery. In a similar study conducted in the same region as this latest one, the archaeologist discovered nearly 175 impressions left behind by the maize weevil, a pest that fed on chestnuts, acorns, or other stored food materials high in starch. Between the maize weevil discovery and this most recent one, Obata says that the humans in the region were likely living relatively settled lives that required them to stockpile food in the longer term. Image courtesy of Prof. Hiroki Obata]]>

Ancient Japanese Cockroach Egg Case Impressions Found